‘Five-fingered Tom’ and ‘Black Harry’: hunters of the Hampshire and Surrey Hills

They weren’t old lags, shifty safe-crackers or Hibernian highwaymen. They were Tasmanian highland snarers who flitted across the public record, leaving just their nicknames to tantalise the curious. ‘Five-fingered Tom’ was a little light fingered. ‘Black Harry’ was dark-skinned aberration in a white society. These traits help us to flesh out the legends of two early fur hunters who might otherwise have stayed as insubstantial as the Holy Ghost.

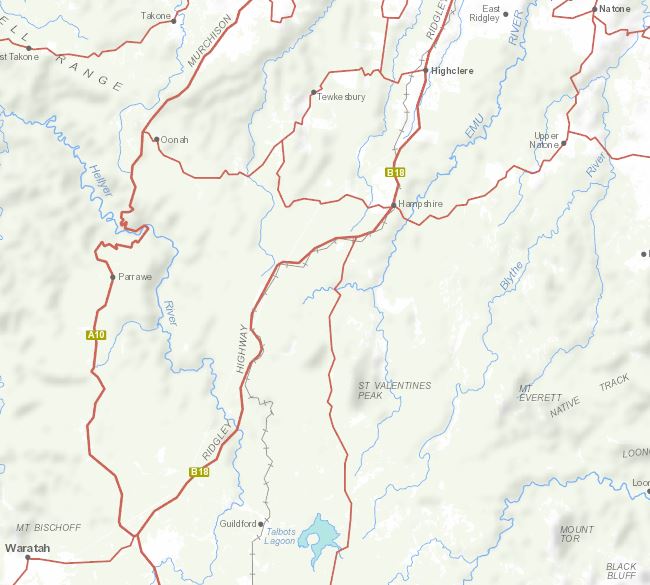

‘Five-fingered Tom’ Jeffries, photographed at the Hobart Penitentiary in 1873 by Thomas J Nevin. Courtesy of the National Library of Australia.

‘Five-fingered Tom’ was Thomas Jeffries. He was born as the second of three children to ex-convicts Thomas Jeffries and Ann Jeffries, née Willis, at Patersons Plains near Launceston in 1841.[1] His father was an illiterate labourer. Thomas Jeffries junior was born with an extra digit on his right hand (that is, five fingers and a thumb), hence ‘Five-fingered Tom’. This made him easily identifiable—good news for the cops! Jeffries regarded Evandale as his native place, but he was living and working on farms in the Sassafras area when in 1873 a warrant was issued for his arrest. The wanted man was described as about 35 years old, 5 feet 9 inches tall, with sandy hair, beard and moustache and a stout build, being ‘a good bushman [who] has spent much of his time hunting’.[2] First offender Jeffries was sentenced to eight years’ gaol for horse stealing. He spent four months making shoes in the Launceston Gaol, from which he vowed that he would abscond at the first opportunity—earning him a transfer to the Hobart Penitentiary.[3] What luck! Since Hobart prisoners were routinely photographed by Thomas J Nevin, we have the image of Jeffries attached to this article. He must have shucked off his bad attitude, since he served only five of his eight years.[4]

Like Jerry Aylett of Parkham, ‘Five-Finger Tom the Hunter’ moved into the high country by the 1880s, a time when Tasmanian brush possum had gained an export market.[5] Possum-skin rugs had been a useful earner for bushmen for decades but now the thicker highland furs had a reputation in the British Isles. In 1883 the ‘Tasmanian Opossum Tail Rug’ could be found alongside the ‘Grey Wolf Rug’, the ‘Silver Bear Rug’, the ‘Leopard, on Bear’ and the ‘Raccoon Tail Rug’ in the catalogue of Liverpool enterprise Frisby, Dyke and Co.[6] Lewis’s in Sheffield, Nottinghamshire, offered ‘real Tasmanian opossum capes’.[7] An 1887 ‘Rich winter fur’ auction in Dundee, Scotland, placed ‘Australian and Tasmanian Opossum’ alongside sealskin, sable, skunk, brown and polar bear, llama, leopard, puma, tiger and raccoon furs.[8]

Waratah, a town born in the early 1870s at the Mount Bischoff tin mine, was a staging-post for both prospectors and hunters. We can follow Jeffries there in 1886 through the digitised pages of the Tasmania Police Gazette. He seems to have found it hard to stay out of trouble, allegedly committing an assault at Waratah before making for the hunting grounds of the Middlesex Plains.[9] Guildford Junction, a village created by the extension of the Emu Bay Railway to Zeehan in the late 1890s, was another hub for bushmen such as Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) timber splitters, hunters and prospectors. Jeffries and his mate Bill Todd were both based there in the period 1903–05, joining fellow hunters ‘Black Harry’ Williams, Tom Allen, the ‘Squire of Guildford’ Edward Brown and, from 1904, Luke Etchell.[10] They had a wide orbit. Todd, for example, was prospecting with George Sloane on the February Plains in 1901 when the latter discovered the body of lost Rosebery hotelier Thomas (TJ) Connolly.[11] Shopkeeper Allen packed stores into the Mayday gold mine under the Black Bluff Range in 1902.[12]

In the years 1888–1909 most of these men supplemented their income by claiming the £1 bounty on the head of the thylacine or Tasmanian tiger. Tom Allen appears to have received fifteen bounty payments—although, as a storekeeper and skins dealer, he may have submitted some applications on behalf of other hunters.[13]

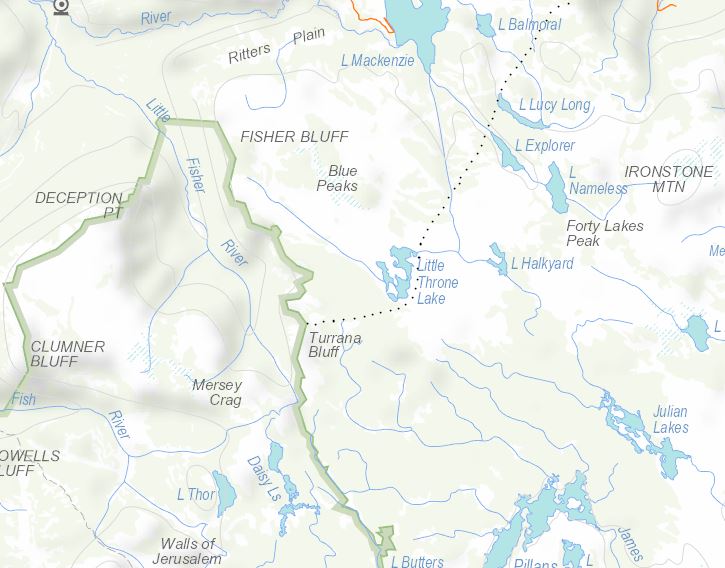

Not so ‘Black Harry’ Williams, the so-called ‘colored king of the forest’, who probably claimed four tiger bounties.[14] He was a short, black-haired Afro-American bush farmer and hunter who arrived in Wynyard in 1887 aged about 24. After serving a month’s gaol for poaching neighbourhood ducks, Williams (‘A black man’!) started operating south of Wynyard (pre-1900), and later at Natone, Hampshire, Guildford and the Hatfield Plains (1900–08).[15] He caught two tigers at the Hampshire Hills in 1900, exhibiting a living one in Burnie. His intention was to sell it to Wirth’s Circus.[16] ‘Black Harry’ was reported to be submitting the other specimen, a very large dead one, for the thylacine bounty, although there is no record of this application.[17] Just enough details of his life survive with which to tell a story. In 1901 he was sued by Chinese storekeeper Jim Sing for failing to pay for a bag of carrots delivered to the Hampshire Hills; Williams counter-sued over Sing’s failure to pay for 100 wallaby skins delivered to Waratah by the hunter.[18] Three years later he was accused of breaking down a VDL Co stockyard at Romney Marsh near the Hatfield River in order to use the timber in a drying shed—making him an early adaptor of this technology (today Black Harry Road recalls his presence in this area). In 1905 Williams was described as the ‘champion trapper and bushman of the State’, the ideal man to lead a search for hunter Bert Hanson who went missing near Cradle Mountain.[19]

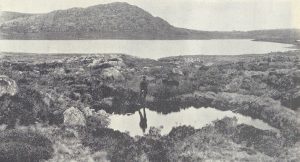

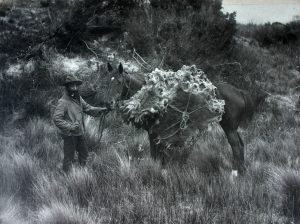

Wallaby hunter Henry Grave demonstrating his reliance on his horse as a pack animal, King Island, 1887. Photo by Archibald J Campbell, courtesy of Museums Victoria.

Jeffries may have been a contender for those honours. Knowledge of his hunting around Cradle Mountain with Todd—another man who flits across the public record—was passed down through generations of bushmen. Drawing on this oral record in 1936, Cradle Mountain Reserve Secretary Ronald Smith unwittingly fused the characters into Tom Todd, aka ‘Five-fingered Tom’. It was on the edge of the high plain they hunted, known as Todds Country, that Hanson died in a blizzard.[20] Correcting Smith’s article, another writer recalled that ‘Tom Jeffrey’ and his Arab pony Dolly were known for many years between Middlesex and Waratah, his mount being ‘the most faithful and gamest bit of horseflesh that ever packed a load over the Black Bluff’.[21] The winter haunts of the highland snarer were very cold, very wet and poorly charted, his comforts simple and meagre, his rewards contingent upon government regulation and global demand. Often he was unseen for months at a time. No newspaper trumpeted his story. Perhaps an extra digit and a different pigment were all that kept Jeffries and Williams from historical anonymity—but I hope there is a lot more to their stories that hasn’t yet been teased out.

[1] Thomas Jeffries senior, transported on the Georgiana, was granted permission to marry Ann Willis, transported on the New Grove, on 3 October 1838, p.88, CON52/1/1; Thomas Jeffries junior was born to Thomas and Ann Jeffries on 1 November 1841, birth record no.1848/1842, registered at Launceston, RGD32/1/3 (TAHO). He had elder and younger sisters: Mary Ann Jeffries, born 24 October 1839, birth record no.1021/1840, registered at Launceston, RGD32/1/3, address was given as Watery Plains; Maria Jeffries, born 11 June 1844, no.271/1844, registered at Launceston, RGD33/1/23 (TAHO).

[2] ‘Warrants issued, and now in this office’, Reports of Crime, 23 May 1873, vol.12, no.723, p.86.

[3] Prison record for Thomas Jeffries, image 25, p.11, CON94/1/2 (TAHO).

[4] ‘Prisoners discharged from Her Majesty’s gaols …’, Reports of Crime, 27 September 1878, vol.17, no.1001, p.157.

[5] See, for example, ‘Commercial’, Launceston Examiner, 24 November 1886, p.2; 19 April 1890, p.2. While William Turner failed to attract a reasonable price for Tasmanian brush possum from English buyers in 1871 (William Turner to the Colonial Treasurer, 27 September and 17 December 1872, TRE1/1/462 [TAHO]), in 1883 HE Button of Launceston began to ship furs to London: ‘Open fur season’, Mercury, 30 July 1926, p.3. For William ‘Jerry’ Aylett, see Nic Haygarth, ‘William Aylett: career bushman’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.28–55.

[6] Frisby, Dyke and Co advert, Liverpool Mercury, 12 November 1883, p.3.

[7] ‘Lewis’s great sale of mantels and furs’, Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 5 February 1886, p.1.

[8] ‘Sales by auction’, Dundee Courier and Argus, 19 November 1887, p.1.

[9] ‘Waratah’, Tasmania Police Gazette, 19 November 1886, vol.25, no.1426, p.187.

[10] Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory, 1903, p.56; 1904, p.412; 1905, p.61.

[11] ‘”Lost and perished in the snow”: another Cradle Mountain tragedy’, Advocate, 27 March 1936, p.11.

[12] Thomas Allen to James Norton Smith, Van Diemen’s Land Company, 28 January 1902, VDL22/1/33 (TAHO).

[13] Bounty no.374, 12 January 1899 (3 adults, ‘3 December’); no.401, 15 November 1900 (3 adults, ’15 June’); no.482, 21 January 1901 (3 adults, ’17 December’); no.22, 4 February 1901 (3 adults, ‘4 January’); no.985, 25 July 1902 (‘July’); no.1057, 27 August 1902 (’15 August’); no.1091, 17 September 1902 (‘4 September 1902’); no.462, 6 August 1903, (1 juvenile, ’24 July’), LSD247/1/ 2 (TAHO). See ‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 15 December 1900, p.2.

[14] ‘Veritas’, ‘The lost youth Bert Hanson’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 11 August 1905, p.2. The bounties were all under the name ‘H Williams’: no.344, 17 November 1899 (’10 October’); no.1078, 11 September 1902 (’31 July 1902’); no.1280, 2 December 1902; no.76, 20 February 1903 (’14 February 1903’), LSD247/1/2 (TAHO).

[15] Williams’ activities at Wynyard in 1887 and 1889 were recorded in the diaries of George Easton, held by Libby Mercer (Hobart). For his conviction on a larceny charge, see ‘Wynyard’, Colonist, 12 October 1889, p.2; and ‘Prisoners discharged …’, Tasmania Police Gazette, 8 November 1889, vol.28, no.1581, p.180. Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory listed H Williams as a hunter living at Wynyard in 1900 (p.223), 1901 (p.239) and 1902 (p.255). Yet he caught two tigers at the Hampshire Hills (Hampshire) in 1900. In June 1903 he advertised for sale a 50-acre farm on Moores Plain Road south of Wynyard (‘For sale’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 June 1903, p.3), and in the period 1903–08 he had a mortgage on a 98-acre block at Natone near Hampshire, which would have been a handy base for his hunting activities (Assessment rolls, Hobart Gazette, 8 December 1903, p.2080; 5 December 1905, p.1847; Tasmanian Government Gazette, 12 November 1907, p.1951; and 30 June 1908, p.739). Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory placed him at Guildford Junction in 1905 (p.61) and 1906 (p.61). ‘Veritas’ placed him at the Hatfield Plains south-east of Waratah in 1905 (‘Veritas’, ‘The lost youth Bert Hanson’).

[16] ‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 21 November 1900, p.2.

[17] ‘Inland wires’, Examiner, 14 December 1900, p.7.

[18] ‘Burnie’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 18 October 1901, p.2.

[19] ‘Veritas’, ‘The lost youth Bert Hanson’.

[20] Ronald Smith, ‘Scene of hunter’s tragic death’, Mercury, 21 March 1936, p.9.

[21] ‘BEG’, ‘Cradle Mountain memories’, Advocate, 24 March 1936, p.6.