by Nic Haygarth | 06/03/20 | Tasmanian high country history

DYI dentistry would make for intriguing reality TV (Channel Seven’s new blockbuster The chair anyone?) but in the nineteenth-century Tasmanian backwoods it was an everyday reality. Many people were far removed from medical services, and if you owned forceps you were licensed to operate. Middlesex Plains stockman Jack Francis (c1828–1912) was a model of self-sufficiency—hunter, stock rider, tanner, bootmaker, rug maker, leather worker, blacksmith, tool maker and dentist. Whether he aspired to more advanced surgery is unknown, but his prowess with the pincers must have made for some tense moments around the family dinner table.

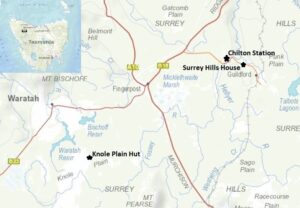

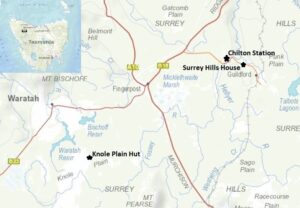

From Chudleigh to Waratah, including the Field brothers’ stations of Middlesex Plains and Gads Hill. Map courtesy of DPIPWE.

Given that 40,000 years of Aboriginal custodianship are unrepresented on official charts of the area, it shouldn’t be surprising that Francis’s comparatively miniscule 40-year familiarity with this former Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) highland run is not recorded on its landmarks. Unlike his notable successor, Dave Courtney (recalled by Courtney Hill), the short, stocky Francis cut no memorable figure. He had no moustaches he could tie behind his back or thick beard to hide his face. Nor was he a ‘man of mystery’, as much as some might have preferred him to be. Francis’s convictism was unpalatable in some quarters even after his death. One newspaper editor omitted the words ‘though a prisoner for some trifling offence’ from his obituary.[1] Highland journalist Dan Griffin was less mealy-mouthed but confused Jack Francis the stockman with Jack Francis the builder and failed assassin.[2] Both men were transported from England to Van Diemen’s Land, the latter for taking pot shots at Queen Victoria, but Jack Francis the stockman was the most benign and pathetic of transportees, being a boy convicted of stealing a barometer.[3] These beginnings make his nickname ‘Jack the Shepherd’, recalling the notorious Irish outlaw, even more ironic.[4]

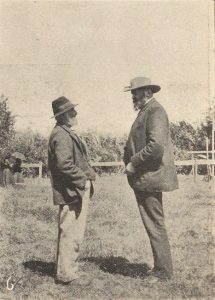

Jack Francis and Dan Griffin at the Chudleigh Races, from the Weekly Courier, 23 January 1904, p.23.

A native of County Armagh, Northern Ireland, Francis was apparently apprenticed as a ‘rough shoemaker’ when he faced court in Lancaster, Lancashire, England.[5] He probably had no idea how those skills would serve him in future years. Measuring all of 167 cm, he must have had a basic education. He could write, but with apparent difficulty, clearly preferring to dictate letters rather than write them himself.[6] Transported for seven years on the Egyptian in 1838, the boy convict served Launceston bootmaker Amos Langmaid before being assigned to rural masters James Grant at Tullochgorum near Fingal and Theodore Bartley at Kerry Lodge near Breadalbane.[7]

By now Francis was getting his leather in the field as well as at the end of an awl. After securing a certificate of freedom in 1845, he was a shepherd at Bentley near Chudleigh before securing his first posting to the highlands.[8] If childhood transportation to the antipodes hadn’t shaken his being to the core, his life now got a mite more adventurous. Because of Legislative Council parsimony, there were few public road bridges in northern Tasmania before 1865, but the VDL Co Track by which the highlands grazing runs were accessed from Chudleigh had dangerous fords much later than that. Negotiating the track for the first time, Francis and his two companions found the Mersey River almost impassable. Jim Garrett took the other two men’s clothes across on horseback, but with such difficulty that he could not return for the men, who of course had no chance of wading the torrent. They therefore had to spend the night without warm clothes or bedding, and were without food until late the next day when crossing became possible.[9]

This was probably in 1851 when grazier William Kimberley became the first victim of a beautiful mirage called the Vale of Belvoir. In that year Kimberley leased 1000 acres of this snowy glacial valley as a summer sheep run, posting Francis as their protector.[10] Barometer boy apparently had more of an issue with ‘wolves’ than with the highland weather. Thylacines—but more likely wild dogs—were said to have decimated Kimberley’s flock, although the survivors thrived, some being too fat to travel.[11]

Perhaps tubby sheep were Francis’s passport to the overseer’s position at Fields’ Middlesex Plains Station. This was a lonely, isolated job, with only the annual muster party and the occasional prospector like James ‘Philosopher’ Smith or surveyor like Charles Gould to interrupt proceedings. However, a routine of maintaining fences, preventing liver fluke in sheep, rescuing stock from bogs and patch-burning the runs left plenty of time for the hunter-stockman’s real occupation, snaring and hunting—primarily for the fur industry, secondarily for meat.

Middlesex Station, 1905, photo by RE Smith, courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Same view of Middlesex Station in 1993, 88 years on. Nic Haygarth photo.

The stock-in-trade of the highland stockman was the brush-possum-skin rug. The cold highland climate necessitated thick furs, and Francis, with his expertise in leatherworking, was well placed to take advantage of the demand for this specifically Tasmanian product.[12] Possum-skin carriage rugs and stock-whips he sold to VDL Co agent James Norton Smith fetched £2 and 16 shillings each respectively.[13] This was useful money, given that a stockman or shepherd’s annual wage was in the range of only £20–£30, supplemented by rations (flour, sugar, tea, tobacco, perhaps potatoes and some meat) delivered to a depot on Ration Tree Creek at the foot of Gads Hill, the milk he could wring from a cow, a few skilling sheep and an abundance of wallaby and wombat meat. He would have grown a few hardy vegetables, guarding them against frost and snow.

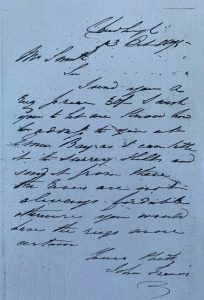

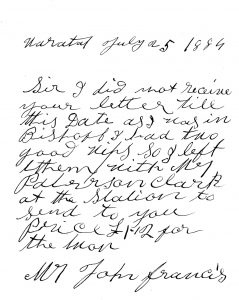

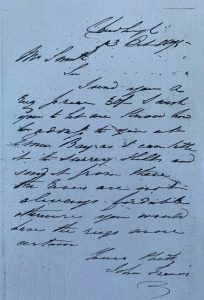

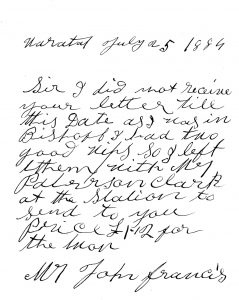

Jack Francis letters to the VDL Co’s James Norton Smith in 1875 and 1884 respectively, showing the difference between Maria’s fluent hand (above) and Jack’s laboured one (below).

From VDL22/1/9 and VDL22/1/12 (TAHO) respectively.

Not every woman would have fancied the lifestyle, but plenty of Jack’s contemporaries were accustomed to hardship. Jack Francis married 29-year-old house maid and factory worker Maria Bagwell (c1830–83) at Deloraine in 1860, subordinating his Roman Catholicism to her Protestantism.[14] She had been transported for seven years for stealing barley meal in Somerset in 1849. Perhaps she needed the nourishment, measuring only 166 cm as a nineteen-year-old. Her prison record is littered with the phrase ‘existing sentence of hard labour extended’. In 1852 she had been ‘delivered of’—deprived of?—an ‘illegitimate child’ at the Female House of Correction.[15] What happened to this unnamed girl from an unnamed father? Just as elusive is George Francis (?–1924), the child apparently born to Jack and Maria Francis during their time at Middlesex.[16]

The house maid seems to have taken to station life. In 1865 Maria Francis escorted surveyors James Calder and James Dooley from Middlesex Station to Chudleigh. To their ‘amazement’, their guide sat astride her horse like a man

‘and thus rode the whole way … with an amount of unconcern that surprised us not a little; and as if determined that we should not lose sight of this extraordinary feat of horsewomanship, she rode in front of us almost the whole distance, smoking a dirty little black pipe from one end of the journey to the other’.[17]

The couple’s son George Francis had arrived by 1871, when a child was mentioned by a visitor to Middlesex. Now Jack Francis revealed himself to be not just a skilled shoemaker and possum-skin rug maker but an expert tanner, clothing himself and his family in leather. They lived

‘in a clean and comfortable hut. A very few minutes sufficed for Mrs Francis to give us a cup of good tea, with abundance of milk, toast, and bread and butter, and when bedtime came she provided us with flealess bed-clothes, an unusual luxury in the bush….’

Jack Francis was ‘a very handy fellow … adept at shoeing a horse or drawing a tooth, having himself made a first-rate pair of forceps with which to perform this last-named operation …’ [18]

Final resting place for Jack and Maria Francis, Old Chudleigh Cemetery. Nic Haygarth photo.

Headstone of Maria Francis, Old Chudleigh Cemetery. Nic Haygarth photo.

Today not even a headstone in the Old Chudleigh Cemetery records this go-getter’s existence. Around Middlesex Station the ‘old’ European names are forgotten: Misery (now Courtney Hill), the Sirdar (after Horatio Herbert Kitchener of the South African War), Pilot, Sutelmans Park, Vinegar Hill, Twin Creeks. Who named them all and why? No journalist interviewed the old station hands. Yet while the Francises left their mark only in written history, digitisation of archival records is enriching our knowledge of displaced people like them, who lived remarkable lives in remote places.

[1] ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[2] ‘DDG’ (Dan Griffin), ‘Vice-royalty at Mole Creek’, Examiner, 15 March 1918, p.6.

[3] See conduct record for John Francis, transported on the Egyptian for seven years in 1839, CON31/1/12, image 175 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/CON31-1-12$init=CON31-1-12p175, accessed 16 February 2020.

[4] For the nickname see, for example, ‘River Don’, Weekly Examiner, 4 October 1873, p.11; ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[5] Francis’s obituarist in, for example, ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4, claimed that he was born at Woodburn, Buckinghamshire, 5 February 1828. Francis’s convict records make him a native of County Armagh.

[6] Indent for John Francis, CON14/1/48, images 25 and 26 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/tas/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fARCHIVES_DIGITISED$002f0$002fARCHIVES_DIG_DIX:CON14-1-48/one, accessed 16 February 2020. Compare, for example, his letter to James Norton Smith, 11 April 1881, VDL22/1/9 (TAHO), written by his wife Maria Francis, with his letter to James Norton Smith, 25 July 1884, VDL22/1/12 (TAHO), written in his own hand after Maria’s death.

[7] Conduct record, as above.

[8] ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[9] ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4.

[10] ‘Crown lands’, Courier, 5 February 1851, p.2; ‘Surveyor-General’s Office’, Courier, 3 December 1851, p.2; ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ‘In the Vale of Belvoir’, Mercury, 15 February 1897, p.3.

[11] ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ‘In the Vale of Belvoir’, Mercury, 15 February 1897, p.3.

[12] HW Wheelright, Bush wanderings of a naturalist, Oxford University Press, 1976 (originally published 1861), p.44.

[13] Jack Francis to James Norton Smith, 10 October 1873, NS22/1/4; and 25 July 1884, VDL22/1/12 (TAHO).

[14] Married 24 December 1860, marriage record no.657/1860, at St Mark’s (Anglican) Church, Deloraine, RGD37/1/19 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=john&qu=francis&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Marriages%09Marriages&qf=NI_NAME_FACET%09Name%09Francis%2C+John%09Francis%2C+John, accessed 15 February 2020. On his marriage certificate, Jack underestimated his age as 28 years.

[15] See conduct record for Maria Bagwell, transported on the St Vincent, CON41/1/25, image 16 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/CON41-1-25$init=CON41-1-25p16, accessed 15 February 2020. See also birth record for Maria Bagwell’s unnamed illegitimate female child, born 7 September 1852, birth record no.1780/1852, registered at Hobart, RGD33/1/4 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=NI_NAME%3D%22Bagwell,%20Maria%22#, accessed 15 February 2020.

[16] George Francis died 12 January 1924, will no.14589, administered 7 March 1924, AD960/1/48, p.189 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=francis&qf=NI_INDEX%09Record+type%09Marriages%09Marriages+%7C%7C+Deaths%09Deaths+%7C%7C+Wills%09Wills&qf=PUBDATE%09Year%091906-1976%091906-1976, accessed 16 February 2020.

[17] James Erskine Calder, ‘Notes of a journey’, Tasmanian Times, 18 May 1867, p.4.

[18] Anonymous, Rough notes of journeys made in the years 1868, ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72 and ’73 in Syria, down the Tigris … and Australasia, Trubner & Co, London, 1875, pp.263–64.

by Nic Haygarth | 05/03/20 | Tasmanian high country history

The palm of being Waratah’s first alcoholic probably belonged to its first resident doctor, John Waldo Pring, a Crimean War veteran who drank himself to death in the years 1876–79.[1] One of his lowest moments came in March 1876 when he escorted a disguised detective to a sly grog shop for a snort.[2] Another who upset early Waratah’s temperance wagon was former Sussex labourer Charlie Drury (c1819–76), who traded native animal hides for rum. For decades before Waratah was born Drury lived a twilight existence remote from civilisation, with often only his dogs, his drink and the spirit world for companions. He even went out on a bender, leaving a legacy of decimated wildlife, delusional folklore and fire-managed grasslands to the hunters and graziers who followed him.

Mount Bischoff, Waratah, Knole Plain and the Surrey Hills. Map courtesy of DPIPWE.

Transported at 20 on a fifteen-year sentence for larceny, the 178-cm tall Drury was no mal-nourished urchin.[3] James ‘Philosopher’ Smith rather generously called him ‘a sturdy type of an Englishman’.[4] Drury could read—books and newspapers were delivered to him in the back country—although no letters survive to testify to his fluency with the pen.[5] Arriving in Van Diemen’s Land in July 1839, he went straight into the assigned service of British pastoral enterprise the Van Diemen’s Land Company (the VDL Co) at the Surrey Hills, working with hutkeeper Edward Garrett and stockkeeper Richard Lennard (c1811–94).[6] The area between the Hellyer River and Knole Plain would be his home for most of his remaining life. His early services to the VDL Co were valued at only £15 per year (when he was stationed at Emu Bay 1845–46) but rose to £30, a typical stockman’s wage of the time, in the years 1850–52.[7] Hunting would have brought in much more than that.

Drury would have been thrown out of his official work when the VDL Co shut down all operations in 1852. He attended the Victorian gold rushes in February of that year, but would have returned to his old haunts after northern graziers the Field brothers (William, John, Thomas and Charles) rented the Surrey Hills in 1853, living chiefly off the proceeds of his unfettered hunting.[8] Of course he also had the gold ‘bug’, finding a little gold at Cattley Plain under the Black Bluff Range in 1857 or 1858.[9]

The old lag was joined at the Surrey Hills by fellow ex-convict Martin Garrett (aka Garrett Martin, c1806–88), who had racked up an impressive record of robbery in Dublin, bushranging in New South Wales and probation served at Port Arthur. Not bad for a dairyman![10] Both men took to hunting, with a little prospecting on the side.[11] Like other highland hunter-stockmen such as Jack Francis of Middlesex Plains, Drury had a little cottage industry going, his specialty being the whittling of celery-top-pine walking sticks manufactured on commission.[12] It would be surprising if he didn’t also make and sell possum-skin rugs, which could fetch £2 each. The two men lived in a surprisingly sumptuous eight-room house with a blacksmith’s shop, stable, out-houses and cattle yards about two kilometres east of the Hellyer River.[13] The cottage was designed for the VDL Co by none other than onetime colonial architect John Lee Archer—something of a comedown from his work on Parliament House and the treasured Ross Bridge.[14]

Drury’s twilight zone

Decades of isolation in the boondocks of failed VDL Co settlements may have taken their toll on Drury. Even well after the tribal Aboriginal people had been driven out of the north-west, the ‘ghosts’ of their clashes with the VDL Co and the isolation played havoc with him. The company’s old Chilton homestead up above the Hellyer River was said to be haunted by the spirits of murdered Aboriginals. Drury reputedly enjoyed being lulled to sleep there by ghostly ‘music’, until one night a more lively manifestation left him crouched in the fireplace with his gun drawn.[15]

Drury sold skins to his former VDL Co workmate and ex-convict Richard Lennard, who was now keeper of the Ship Inn at Burnie. Lennard would regularly bring a horse and dray up to Drury containing grog and rations, returning to Burnie with the skins. On one occasion when Lennard was arriving at Surrey Hills, Drury came out to meet him, calling out, ‘I know what you are going to tell me—Jack Flowers is dead.’ This referred to the ex-convict known as ‘Forky Jack’, a previous workmate, who had died recently. Lennard knew that Drury had had no contact with the outside world during that time, so how could he possibly know of Flowers’ death? ‘He passed over here’, Drury told him, calling ‘Charlie [distant], Charlie [loud], Charlie [distant]’—on his way to hell.[16] James ‘Philosopher’ Smith got the same story from Drury, who had heard Flowers calling him ‘in the most hasty manner possible while very quickly passing through the air’. The hallucination, if that is what it was, apparently occurred at about the time of Flowers’ death.[17]

Drury had other supernatural experiences/hallucinations and beliefs. One day he was out hunting not far from home when it came on dark. He sat down under a tree for a nap, intending to hunt badgers (wombats) when the moon rose. He was awoken by a clap on the shoulder and the words, ‘Charlie! Didn’t you say you were going to start out after the badgers as soon as the moon was up? Here it is more than three hands high’. The speaker, Drury told his friend William Lennard, wore a sleeved waistcoat and an English top hat. Drury gathered his dogs, including Long Jim, who his new friend pointed out to him a little way off, and as he did so the apparition ‘backed away through a swamp and faded out’.[18]

On another occasion Drury and William Lennard were camped at an isolated place called Sutelmans Park somewhere near Bonds Plain (east of the Vale of Belvoir). Come morning Drury declined to leave camp, having been warned by the banshee (a female Irish spirit who heralds death) during the night that some misfortune would befall him if he did so. Lennard persuaded Drury to disregard the warning, and they went out hunting with Drury’s favourite dog Turk. Later that morning they found the dog dead. ‘There you are’, Drury remarked, ‘what did I tell you?’ Drury then tried to bring the dog back to life by ‘wailing’ over it. Lennard recalled laughing at him for being so foolish, whereupon Drury ‘levelled his gun at him and threatened to blow his head off’. Realising the precariousness of his position, Lennard quickly came to his senses.[19]

In the early 1870s Drury’s unusual ways made it into an international travel book. When an 1871 party visited the Surrey Hills, Drury fed them cold beef, and the visitors got to try those famous possum-skin rugs, which, as was customary, were alive with fleas. While his guests battled these, Drury went badger hunting by the light of the moon with about a dozen kangaroo-dogs, bringing home three skins and one entire animal—presumably for breakfast. As he explained at the dining table, ‘the morning after I have been out badger-hunting at night I always eat two pounds of meat for breakfast, to make up for the waste created by want of sleep’. Drury also recalled his pack of ferocious hunting dogs falling in with a ‘flock’ of seven ‘hyenas’, four thylacines being killed at a time when, unfortunately for him, there was no government thylacine bounty.[20]

Drury and the Bischoff tin

Through the 1850s and 1860s the VDL Co was tantalised by reports of gold discoveries on or near its land. The company’s local agent, James Norton Smith, appears to have placed some faith in Drury as a potential gold discoverer, following his claim to have found gold at the Cattley Plain, and as late as 1872 offered him prospecting tools and discussed a reward for discovery of payable gold.[21]

Prospector James ‘Philosopher’ Smith got to know Drury, calling at his cottage in December 1871 when short of food after discovering one of the world’s greatest tin lodes at Mount Bischoff. Drury had seen Smith pass by on his way to Bischoff, and now expressed surprise that he was able to stay out in the bush so long. He also told Smith that he had no food—a statement that no doubt sent a shock wave through the enervated prospector. However, relief was at hand:

‘He [Drury] replied that what he meant was that he had no beef but had kangaroo, bread and tea. He hurriedly invited me into the house and commenced to prepare a meal with the utmost celerity. He slung a camp oven containing fat and then seized a chopper with one hand and a leg of kangaroo with the other and in a few minutes he had some of the meat frying while he also attended to the tea kettle.’[22]

Smith would have found accounts of this visit written long after his death harder to swallow. In 1908 and 1923 claims were made that Smith found the Mount Bischoff tin in Drury’s hut. ‘There’s a mountain of it just outside there’, Drury apparently told Philosopher, sending him a few metres to the summit of the mountain.[23] Why anyone who had been at Waratah in its early days, when Mount Bischoff was accessed via a tunnel through the horizontal scrub, would suggest the existence of a stockman’s hut in such a position it is hard to imagine.

Drury was the stuff of which disenfranchised prospectors are made, the bumpkin shepherd who stumbles upon a fortune. The strongest argument against the Drury discovery story—apart from his stock of hallucinations—is Smith’s unblemished reputation for integrity. The closest that Drury is likely to have got to the Bischoff scrub is the very edge, where the wallabies snoozed before making their way to the grassy plains at night to feed.

Protective of his father’s reputation and achievements, Garn Smith interviewed Jesse Wiseman and William Lennard, both of whom had hunted with Drury in the early 1870s. Both said that Drury never claimed to have found the Mount Bischoff tin.[24] Wiseman recalled Drury saying, ‘Just fancy us hunting about here all these times and not knowing anything about [the Mount Bischoff tin]‘.[25]

Yet other Drury acquaintances told a different story. An anonymous source claimed that ‘old Charlie Drury made no secret about telling travellers in those days that he directed Mr James Smith to where the tin was, he having a few specimens of this strange metal in his hut, which he showed to “Philosopher” Smith, who continued the quest …’[26]

Grazier John Bailey Williams was another to vouch for Drury, telling Lou Atkinson ‘I ought to have found Bischoff as Drury told me of the mineral, but I paid no attention to him. I had heard so many wild stories of this sort’.[27] Williams had encountered Drury while trying to run sheep in the open grasslands at Knole Plain in 1864–65.[28] His application to lease 6500 acres of Crown land there foundered, with many sheep reportedly starving to death.[29] Well might he have wished for a tinstone saviour!

However, it seems that wild stories were Drury’s stock in trade. It wouldn’t be at all surprising if the old sot had mineral samples in his hut—but it would be a great shock if they were cassiterite specimens.[30]

Opportunity knocks

The Mount Bischoff Tin Mine and its new trade route with Emu Bay brought financial opportunity to previously remote hunter-stockmen. Fields’ Hampshire Hills overseer Harry Shaw wanted to set up an ‘eating house’ along the road. [31] Garrett must have had similar commerce in mind when he tried to buy land at the Hampshire Hills.[32] He later drove the VDL Co Tram between Emu Bay and Bischoff and worked as a blacksmith at the Wheal Bischoff Co Mine.[33] Drury became a commercial operator. He and his mate John Edmunds established a base on the hunting ground of Knole Plain, leaving Garrett to hunt the Surrey Hills. Their hut stood right along the track to the mountain, on grasslands that the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Company wanted to keep for feed for the bullock and horse teams carting between Waratah and the port at Emu Bay. They were professional hunters paying a £1 annual licence and returning up to £70 per season for shooting 600 to 1000 wallabies as well as the brush possums which formed their possum-skin rugs—at least that was told they told a visiting reporter.[34] The suggestion that such men obeyed government regulations is ludicrous. Additional money was to be had packing supplies for mining companies, as well as supplying Waratah with wallaby meat and some of the grog that they received from Emu Bay.[35] Feeding 20 kangaroo dogs alone would necessitate constant hunting.

Mount Bischoff from Knole Plain, 2009. Nic Haygarth photo.

The new trade route through to Emu Bay also gave hunters like Drury and Garrett better access to skin buyers—although their attempt to sell the skins of Drury’s beloved badger seems to have foundered. [36] While Garrett and Drury were out hunting, their charges—the Field brothers’ notoriously wandering cattle—wandered onto Waratah dinner plates, much to their owners’ disgust. In 1874 Thomas Field called for police intervention.

So did the Mount Bischoff Company when the first pub opened in town.[37] Drury’s unofficial pub never closed. One man was discharged from Walker and Beecraft’s tin claim for getting drunk there.[38] Drury himself was likely to get ‘on the spree’ at any time, making him an unreliable employee.[39] There was a celebrated incident in which Drury got hammered on a keg of rum and accidentally burned down his and Edmunds’ hut, destroying not only his own skins and stores but supplies belonging to prospectors Orr and Lempriere and surveyor Charles Sprent. The only thing salvaged was the keg, to which the hunter was said to have clung ‘with the affection of a miser’.[40]

Drink eventually killed Drury in his hut at Knole Plain. James Smith learned that:

‘His end was a melancholy one. He had been drinking somewhat heavily when two Christian men from Waratah went to see him at his hut … While talking to his new friends he lay down on his bed and seemed to doze but when after a time one of them tried to rouse him it was found that he was dead.’[41]

Detail from Charles Sprent’s January 1874 map, ‘Plan of agricultural sections on Knole Plain, County of Russell’, showing ‘hut and kennels’ (upper right, just above the road reserve. AF396/1/806 (TAHO).

Potential rubble from Drury’s hut protruding from the furrows of a future plantation on Knole Plain in 2009. Presumably Drury remains buried here, although the eucalypt that marked the spot is long gone. Nic Haygarth photo.

Finding Drury

Drury is said to have been buried beneath a eucalypt near his hut on Knole Plain.[42] Did anything remain there of either his hut or his grave? Examining an old map of Knole Plain more than a decade ago, Burnie surveyor and historian Brian Rollins found the notation ‘hut and kennels’. Brian was interested to find a James Sprent survey cairn that was marked on the same map. We resolved to combine our interests and, under the stewardship of Robert Onfray from Gunns, we made a trip to the Knole Plain area. We found ploughed remains of a long-fallen building which suggested Drury’s hut or some later version of it. No weathered cross tilted over the detritus. No bleached bones poked out of the furrows of the plantation coup. Perhaps Charlie Drury is six feet under the tussock grass, raising a toast with his insubstantial friends, his beloved dogs crashing through some underworld after twilit kangaroo, badger and tiger.

[1] ‘Mount Bischoff’, Devon Herald, 27 September 1879, p.2; he died of natural causes, 19 September 1879, inquest SC195/1/60/8154 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, afterwards TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/SC195-1-60-8154, accessed 29 February 2020.

[2] ‘Sly grog selling at Mount Bischoff, Cornwall Chronicle, 27 March 1876, p.3.

[3] Drury was transported on the Marquis of Hastings. See his conduct record, CON31/1/12, image 31 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/CON31-1-12$init=CON31-1-12p31, accessed 1 March 2020, also Description list, CON18/1/16, p.200 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=drury#, accessed 23 February 2020.

[4] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/14/1/ 3 (TAHO).

[5] Cavanagh (?) to James Smith, 24 January 1875, no.38, NS234/3/1/4 (TAHO).

[6] VDL61/1/2 (TAHO). For Lennard see conduct record, CON31/1/27, image 179 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/CON31-1-27$init=CON31-1-27p179, accessed 1 March 2020.

[7] VDL133/1/1 (TAHO).

[8] From Launceston to Melbourne on the City of Melbourne, 3 February 1852, POL220/1/1, p.558 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=drury#, accessed 23 February 2020. Drury’s sentence expired in March 1853, leaving him free to choose his employer (‘Convict Department’, Launceston Examiner, 19 March 1853, p.6).

[9] See WR Bell, ‘Report on the hydraulic gold workings at Lower Mayday Plain …’, 14 May 1896, EBR13/1/2 (TAHO). In June 1858 a prospector W MacNab testing the Hampshire and Surrey Hills for gold complained that a mining cradle he expected to use had been removed for use by a stockkeeper from the Surrey Hills Station. See W MacNab to James Gibson, VDL Co agent, 9 June 1858, VDL22/1/2 (TAHO).

[10] See his conduct record, CON39/1/2, p.334 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=Martin&qu=garrett, accessed 23 February 2020. After a stint in the New Town Invalid Depot (admitted 24 November 1886 to 17 December 1886, POL709/1/21, p.207) Garrett died of ‘dropsy’ (oedema, fluid retention) in Launceston in 1888 when he was said to be 82 years old (2 December 1888, death record no.391/1888, registered in Launceston, RGD35/1/57 [TAHO]).

[11] Garrett may have discovered the barytes deposit at the Two Hummocks near Fields’ Thompsons Park Station (James Smith to Ritchie and Parker, 10 July 1875, no.327, VDL22/1/4 [TAHO]).

[12] Richard Hilder, ‘The good old days’, Advocate, 5 January 1925, p.4; Charles Drury to James Norton Smith, 24 July 1872, VDL22/1/4 (TAHO).

[13] ‘Country news’, Tasmanian, 30 August 1873, p.5; G Priestley, ‘Search for Mr D Landale’, Weekly Examiner, 11 October 1873, p.19.

[14] Agreement between the VDL Co and builder George Fann, 4 March 1851, VDL19/1/1 (TAHO). Fann was paid £150 for the job on 19 April 1852 (VDL133/1/1, p.153 [TAHO]). Archer sent two designs for a stockkeeper’s hut to James Gibson on 17 February 1851, although unfortunately the designs cannot be found on file (VDL34/1/1, Personal letters received by James Gibson [TAHO]). See also the 1842 census record for Richard Lennard, who was then living at the VDL Co’s old Chilton homestead. He was one of ten men from the ages of 21 to 45 resident there at the time, only one of whom arrived in the colony free, while another qualified under ‘other free persons’. Two who were in ‘government employment, six in ‘private assignment’. Two were ‘mechanics or artificers’, two were ‘shepherds or others in the care of sheep’, five were ‘gardeners, stockmen or persons employed in agriculture’ and one was a ‘domestic servant’ (CEN1/1/8, Circular Head, p.63 [TAHO], https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=richard&qu=lennard, accessed 1 March 2020).

[15] William Lennard, quote by RS Sanderson, ‘Discovery of Tin at Mount Bischoff’, RS Sanderson to Arch Meston, May 1923?, M53/3/6 (Meston Papers, University of Tasmania Archives, Hobart).

[16] William Lennard, quoted by RS Sanderson, ‘Discovery of Tin at Mount Bischoff’.

[17] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/14/1/ 3 (TAHO).

[18] William Lennard, quoted by RS Sanderson, ‘Discovery of Tin at Mount Bischoff’.

[19] William Lennard, quoted by RS Sanderson, ‘Discovery of Tin at Mount Bischoff’.

[20] Anonymous, Rough notes of journeys made in the years 1868, ’69, ’70, ’71, ’72 and ’73 in Syria, down the Tigris … and Australasia, Trubner & Co, London, 1875, pp.263–64.

[21] James Norton Smith to VDL Co Court of Directors, Outward Despatch 38, 15 May 1872, p.482, VDL1/1/6; James Norton Smith to Charles Drury, 12 June 1872, p.493, VDL7/1/1 (TAHO).

[22] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/14/1/ 3 (TAHO).

[23] ‘Patsey’ Robinson, quoted in ‘The oldest inhabitants’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 24 April 1908, p.2.

[24] GH Smith, ‘The true story of Bischoff’, Advocate, 1 May 1923, p.6.

[25] Jesse Wiseman quoted by RS Sanderson, ‘Discovery of tin at Mount Bischoff’.

[26] ‘1866’, ‘Discovery of tin at Mount Bischoff’, Advocate, 30 April 1923, p.6.

[27] John Bailey Williams, quoted by RS Sanderson, Discovery of Tin at Mount Bischoff’.

[28] John Bailey Williams to Charles H Smith, Du Croz & Co, 25 January 1865; and to VDL Co agent Charles Nichols, 11 April 1865, VDL22/1/3 (TAHO).

[29] Thomas Barrett to R Symmons, 2 March 1867, VDL22/1/3 (TAHO).

[30][30] Thomas Broad claimed to have seen tin specimens in Drury’s hut—but did Broad have enough expertise in mineralogy to make that call? See Thomas Broad, ‘Mt Bischoff’s early days’, Advocate, 3 May 1923, p.2.

[31] James Smith to Ferd Kayser, 15 January 1876, NS234/2/1/2 (TAHO).

[32] James Smith to Martin Garrett, 30 June 1875, no.310, NS234/2/1/2 (TAHO).

[33] Hugh Lynch to James Norton Smith, 23 April 1877, VDL22/1/5; Daniel Shine to James Norton Smith, 27 October 1879, VDL22/1/7 (TAHO).

[34] ‘Country news’, Tasmanian, 30 August 1873, p.5.

[35] For packing, see WR Bell to James Smith, 20 July 1875, no.335; and Joseph Harman to James Smith, 11 October 1875, no.450, NS234/3/1/4 (TAHO).

[36] AM Walker to James Smith, 11 February 1873, no.115, NS234/3/1/2 (TAHO).

[37] Minutes of directors’ meetings, Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Company, 7 September 1875, NS911/1/1 (TAHO).

[38] Mary Jane Love to James Smith, 12 October 1873, no.290/291, NS234/3/1/2 (TAHO).

[39] William Ritchie to James Smith, 9 March 1874, NS234/3/1/3 (TAHO).

[40] ‘Trip to Mount Bischoff’, Mercury, 18 December 1873, p.3.

[41] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/14/1/ 3 (TAHO). Drury died 3 March 1876, death record no.151/1876, registered at Emu Bay, RGD35/1/45 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=drury#, accessed 23 February 2020. Cause of death was given as ‘excessive drinking’.

[42] ‘An Old Hand’, ‘The O’Malley and the Labor Movement in Tasmania’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 28 May 1908, p.2.

by Nic Haygarth | 21/07/19 | Tasmanian high country history, Tasmanian landscape photography

Hikers love drama. Launceston photographer Steve Spurling (Stephen Spurling III, 1876‒1962) manufactured some in 1908 when he set out on a hike with his mates Knyvet Roberts (1872‒1959) and John Burns (Jack) Scott (1873‒1915). Their journey to Lake St Clair was ‘a terror incognito!’, since they could get ‘no reliable information as to what lay before us, and were not encouraged by rumours of precipitous valleys and impassable bogs …’[1]

In other words, Spurling didn’t know who to ask for information on his proposed route. In 1908 there were no walking clubs which later acted as a repository of local hiking knowledge. Spurling had few useful maps and no access to the shepherds and hunters who had been working the lake country for decades. Had he only known, in five minutes he could have hotfooted it from his office at Spurling Studios down to the legal firm of Law & Weston & Archer, two of the principals of which had, as schoolboys, crossed the lake country to Lake St Clair 22 years earlier.[2] Or called on Delorainite Dan Griffin, the temperamental highland journalist who had scouted the Lake Ina area for a west coast stock route, finding only a thylacine in the business of taking a leg of mutton home to her family.[3] These men could have told him where to go and what to expect.

Clean-shaven and steely-eyed, Jack Scott, Knyvet Roberts and Stephen Spurling III ready themselves for their two-week hike, 1908. Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of the late Barney Roberts.

Spurling was then at the height of his physical powers, being instructor to the Union Jack Gymnasium Club.[4] Knyvet Roberts, a fellow traveller on Spurling’s 1905 Cradle Mountain climb, and Jack Scott, with whom Spurling had sporting connections (Union Jack Gymnasium Club, lacrosse and rifle shooting), are also likely to have been in fine fettle. They sure looked that way when Spurling photographed them gazing steely-eyed across a paddock somewhere between Deloraine and Western Creek. While his mates toted simple haversacks, Spurling, in addition to his swag and photographic case, slung a bag around his neck. How did his glass plates ever survive long enough to be processed, let alone exposed? More importantly, when did the cravat cease to be a bushwalking accessory and are we the poorer for it?

‘A pine belt, Western Highlands’, 1908, Roberts and Scott approaching a pencil pine grove on a highland lake. Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

‘On the Pine River Divide, Central Plateau’, 1908, Roberts and Scott take a breather on the Great Pine Tier at one of the many tarns encountered. Brooding skies are a feature of this excursion record. Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

Spurling’s purpose was to supplement the landscape catalogue of Spurling Studios. The Daily Telegraph’s Deloraine correspondent must have been suffering his own ‘terror incognito’, judging by his description of the party’s plans to cross ‘via Mount Ironstone and Lake St Clair for Cradle Mountain’.[5] The trek started inauspiciously. Alighting from the Higgs Track into a Lake Balmoral blizzard, the men set the compass for Mount Olympus, about 50 kilometres away as the crow flew. Twenty-seven-kilo packs barely provisioned them for the five days of tramping ahead, with innumerable detours around tarns, battles with bauera and dense Richea scoparia (‘gas bush’), and even a near thing with quicksand. At nightfall on Day Two they camped near ‘the lakes of the Hay Moon Marshes’ (presumably Chummy Lake and Lake Denton, near Halfmoon Marsh, Pine River) on the Great Pine Tier.

‘The Courier Lake, Western Highlands’, 1908. Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

Lake Spurling (now Lake Riengeena), 1908, Stephen Spurling III photo from the Tasmanian Mail, 12 September 1912, p.24.

‘Lake Laura, Western Highlands’, 1908. In 1896 Beattie had taken the Sublime approach to Mount Ida’s towering form above this lake. Spurling’s elegantly framed photo instead captured the mountain reflections, belying the difficulty of access to the site. Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

From here the trio must have swung around to the west. On Day Four they approached a large, uncharted, unnamed lake ‘almost due south of Rugged Mt [a named then used to describe the group of peaks from the Walls to Mount Rogoona and those overlooking Lees Paddocks], ’ measuring about three miles long and three-quarters of a mile wide—possibly Lake Norman or Lake Payanna in the Mountains of Jupiter. This was probably the feature Spurling dubbed the Courier Lake. Was he buttering up the Weekly Courier newspaper that bought so many of his photos? Spurling’s companions also named another lake (now Lake Riengeena) after him at the time. The serrated head of the Acropolis now loomed high in the summer haze far across the Narcissus Valley. Rounding the shoulder of ‘an unnamed mountain’ (now Mount Spurling), they scrambled down the Traveller Range to camp at Lake Laura, just to the north-east of Lake St Clair.

‘From Mount Olympus, Lake St Clair’, 1908, a misty lake shot from the rock scree high on the mountain. Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

‘Drifting mists, Mount Olympus’, 1908, showing the party’s campsite at Narcissus River. Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of Libraries Tasmania.

On Day Seven Spurling’s party resettled at the mouth of the Narcissus River, a site which would find favour with future Lake St Clair campers. After a week’s exertion, the photographer was too knackered to attend the usual dawn service of his profession. He had not stirred from his bed next morning when one of his mates roused him, ‘Steve, get up, there’s a cloud over Mount Olympus!’ By the time the lens was brought to bear, the rising mist cloaked only the mountain’s lower baffles, resulting in one of Spurling’s most striking compositions.

‘The Du Cane Range [the Guardians] from Lake Marion’, 1908. Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

Spurling’s ‘Mount Gould, Lake Marion’, 1908, seems rather tame compared to Beattie’s Sublime version shot twelve years earlier. Was the pandanus planted? Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of Stephen Hiller.

‘Cuvier Valley and Mount Olympus’, 1908. The party pauses for the photographer on its half-starved rush to Cynthia Bay. Stephen Spurling III photo courtesy of the late Barney Roberts.

Food supplies were now desperately low. After conquering Mount Olympus, base camp was moved to the Byron Gap in hope of landing some game. ‘Hedgehog’ (echidna) stew had fed the party for a while, but their snares continued to draw a blank. Lake Marion, Mount Gould and the Cuvier Valley completed the sightseeing, before the visitors made a dash for the accommodation house at the southern end of the lake, hoping to beg provisions from other tourists. The place was empty—but for a small packet of flour. Spurling, Scott and Roberts quickly turned this into a barely edible rock-hard damper. Appetites whetted, they determined to partake of the superior cuisine available at the Pearce residence, 20 kilometres away. There the ‘three wild eyed haggard bearded sun-downers’ must have presented quite a sight hoeing into their ‘Lord Mayors Banquet’.

Homeward bound, they took the stock track from Bronte to Great Lake, reaching the shepherd’s hut at the Skittleball Plains near Great Lake on the twelfth night of their journey. The 4139-acre sheep run between the Ouse and Little Pine Rivers was stocked by Edmund Johnson of Lonsdale, near Kempton. The identity of his shepherd is unknown, but he kindly offered the party his floor. Revived by their hearth-side sleep, Spurling, Scott and Roberts pulled out all stops for the final dash along the lake and down Warners Track, taking their tally for the last three days of the tramp to 130 kilometres. The reason for their haste was that at the Pearce homestead arrangements had been made to have a driver await the party with a dray at Jackeys Marsh. ‘The luxury of driving was unspeakable’, Spurling wrote in an excursion diary which, like the 1840s survey maps that might have aided him, was never published.

Spurling’s photos from the trip featured in the Weekly Courier newspaper over many months.[6] They also appeared as postcards (they are collectables today) and in ‘bioscope’ lantern slide performances which Spurling conducted in Launceston, that is, as slides incorporated into a moving picture show.[7] In 1913 he would return to Lake St Clair with a movie camera, as Simon Cubit and I detailed in Historic Tasmanian mountain huts.[8]

Major Jack Scott was killed in action at Gallipoli on 8 October 1915, having joined up in Western Australia alongside his brother Joe Scott—who likewise lost his life during the Dardanelles Campaign.[9] Knyvet Roberts, after whom Knyvet Falls, Pencil Pine Creek, are named, became a Flowerdale farmer. His son, the writer Bernard (Barney) Roberts, treasured an album of 30 photos which Spurling had given his father after the 1908 Lake St Clair trip. Barney used these photos to introduce me to the photography of Steve Spurling, for which, 30 years later, I am extremely grateful.

[1] Spurling’s unpublished account of the trip, ‘Across the Plateau’, is held by the Spurling family in Devonport. It appears to be a typed version of hand-written Spurling notes and is wrongly dated February 1913, giving the impression that the author and the typist were not one and the same.

[2] For the accounts of this trip see ‘The Tramp’ (William Dubrelle Weston), ‘About Lake St Clair’, The Paidophone, (Launceston Church of England Grammar School magazine), vol.II, no.7, September 1887, pp.7‒8; and ‘Shanks’s Ponies’ (William Dubrelle Weston), ‘A trip to Lake St Clair’, Examiner, 22 December 1888, p.2 and 29 December 1888, p.13. For Weston and Law’s hiking careers, see Nic Haygarth, ‘”The summit of our ambition”: Cradle Mountain and the highland bushwalks of William Dubrelle Weston’, Papers and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association, vol.56, no.3, December 2009, pp.207‒24.

[3] ‘Lake Ina’, Daily Telegraph, 24 May 1907, p.4.

[4] ‘Union Jack Gymnasium Club Annual Meeting’, Daily Telegraph, 17 March 1908, p.8.

[5] ‘Deloraine’. Daily Telegraph, 18 February 1908, p.7.

[6] Photos from the 1908 trip appeared in the Weekly Courier on 16 April 1908, p.27; 23 April 1908, p.19; 30 April 1908, p.17; 7 May 1908, p.17; 14 May 1908, p.17; 21 May 1908, pp.21 and 22; 28 May 1908, p.17; 11 June 1908, p.24; 2 July 1908, p.17; 9 July 1908, pp.17 and 23; 16 July 1908, p.22; 23 July 1908, p.23; 6 August 1908, pp.20 and 24; 31 December 1908, pp.21 and 24.

[7] See, for example, ‘Bioscope entertainment’, Daily Telegraph, 29 September 1908, p.3.

[8] ‘Hartnett’s huts’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Historic Tasmanian mountain huts: through the photographer’s lens, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2014, pp.76‒83.

[9] ‘Major JB Scott killed: brothers make the supreme sacrifice’, Examiner, 16 October 1915, p.6.