by Nic Haygarth | 28/07/17 | Tasmanian high country history

Jim Stacey, with beard and hat, peering into the camera, at a public function late in life. Photo courtesy of Maria Stacey.

It was Tasmania’s biggest rush since the Lisle gold craze of 1879. The year was 1925, the commodity was osmiridium, the place was the Adams River, 120 km west of Hobart—and the name on everybody’s lips was Stacey.

Two generations of Staceys, a Tasman Peninsula family, drove the discovery and development of what became Adamsfield. Yet the story of the brothers Jim and Tom Stacey shows how capriciously fortune was apportioned to mineral prospectors. Perhaps Jim Stacey somehow offended St Barbara, patron saint of miners. For all his initiative and enterprise in the field, he made no money. His brother, on the other hand, turned up when the work was done and made a killing.

Jim Stacey was born at Port Sorell on 28 October 1856 to Robert Stacey and Kara Stacey, née Eaton.[1] As a young man, tin commanded his attention. By the age of 20 he was at Weldborough, on the north-eastern tin fields, with two of his brothers, one of whom died there from suspected exposure.[2] Jim Stacey then went to the Mount Bischoff tin mine at Waratah, where his mining education continued. He recalled meeting the mine’s discoverer James ‘Philosopher’ Smith, and learning from him the importance of testing river sands for minerals. Stacey benefited from meeting some of the best prospectors on the west coast—WR Bell (discoverer of the Magnet mine), George Renison Bell (Renison), the McDonough brothers (Mount Lyell), Frank Long (Zeehan) and others. The independence of these men impressed him. He was probably at Mount Lyell in 1886 during the excitement over the Iron Blow, and he later recalled testing the Franklin River for gold.[3]

The Mount Bischoff Co and Don Co plants at Waratah, c1890, courtesy of the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

While at Waratah, Jim Stacey had also married Henrietta Davis.[4] Perhaps the couple had put away some money, because they established a farm at Nubeena on the Tasman Peninsula, where the Stacey family were now settled. By 1907, when he was 51 years old, Jim Stacey was a respectable member of Peninsula society, being an inaugural member of the Tasman Municipal Council.

Jim Stacey’s much younger brother Thomas Arthur Stacey was also a mineral prospector, but there the similarities end. Tom was also born at Port Sorell, but in 1877, 21 years after Jim.[5] Little is known of his early years until in 1906 he married Edith Grace Wright at Koonya on the Tasman Peninsula.[6] To say the marriage was an unhappy one would be an understatement.

During World War One (1914–18), Jim Stacey was the model of patriotism, ‘sending’ five sons to the battlefields and being active in recruitment.[7] Two of those sons were killed, another two were wounded.[8] Other people sought an escape in the war. So it was for Tom Stacey, who must have owned the most peculiar war record in his family. He enlisted at Claremont, Tasmania, under the alias John West to avoid maintenance payments to his estranged wife and children.[9] When the police tracked him down, he deserted, eventually re-enlisting, under his real name, at Cloncurry in outback Queensland. Stacey reached Cape Town on the troop ship Wyeema in 1918, just as the Armistice was being signed. Returned to Sydney with the rest of the 7th General Reinforcements, he was arrested as soon as he was discharged.[10]

In his sixties, Jim Stacey was reborn as a prospector. The catalyst for it was the discovery of belts of serpentine, the host rock of osmiridium, in south-western Tasmania. In 1924 he led a party which included Fred Robinson, Edward Noye, and his sons Sydney and Stanley Stacey to Rocky Boat Harbour (Rocky Plains Bay) near New River Lagoon. Announcing the discovery of osmiridium there, the old Bischoff man proudly asserted his independence, stating that he took no aid from the government, having first found the metal while prospecting on his own account months earlier.[11] The first sale of osmiridium from southern Tasmania was in January 1925 when Arthur (AH) Ashbolt of AG Webster & Son in Hobart bought a 25-3-13-oz parcel worth £780-10-0 from Nubeena men Robinson, Noye, Jim Stacey and C Clark.[12]

In November 1924 Arthur, Sydney and Charles (‘Brady’) Stacey, plus ‘Archie’ Wright and Edward Bowden of Hobart retraced Government Geologist Alexander McIntosh Reid’s steps by working their way along the South Gordon Track to the Gordon River, then back along the Marriott Track to the Adams River Valley, discovering osmiridium on the western side of the Thumbs.[13] Wanting confirmation of their find from the experienced Jim Stacey, they arranged to meet him at the Florentine River in February 1925. Jim Stacey and party made their own osmiridium discovery independently on a different site near the head of Sawback Creek, the eastern branch of the Adams River, 120 km west of Hobart by railway, road and sodden, steep mountain track.[14]

From July to September 1925, a quarterly record 1078 miner’s rights were issued in Tasmania, as diggers rushed the field.[15] Jim Stacey was reported to have chosen his reward claim hastily, and won little from it, whereas, ironically, his brother Tom, who had had no part in the early expeditions, ended up with the best claim on the field.[16] In the December quarter for 1925 alone, Tom Stacey pocketed £1186—the equivalent of a six-figure sum today.[17]

Adamsfield diggers in the snow, autumn 1926. Alf Clark photo courtesy of Don Clark.

Adamsfield ‘new chum’ Horace ‘Jimmy’ Lane recalled turning down Tom Stacey’s invitation to join him as a partner in that rich claim. Lane disliked and feared the unshaven, unkempt ‘Old Tom’, attributing his manner and habits to over-indulgence in rum. Old Tom was well known for the ‘boom and bust’ lifestyle that must have been little comfort to his long-suffering family.[18] North-eastern identity Bert Farquhar may have been exaggerating when he alluded to Tom leaving the field with £12,000 and returning two years later unable to afford a horse to carry him, but the lesson was obvious.[19] Lane told the tale that

‘on one occasion Old Tom had crossed Liverpool Street [Hobart] to test the quality of the liquor at the Alabama Hotel. A naval vessel was in port and there were quite a few sailors in the bar of the Alabama and Tom was getting somewhat more inebriated than usual. He finally reached the point of no return: he offered to fight anyone in the bar for £10 and threw a tenner on the bar to back himself. One of the naval chaps agreed to fight him so Tom demanded that his tenner be covered. However when he turned around there was no money on the counter and no one present would admit having touched it. Tom staggered back to the Brunswick [Hotel, on the opposite side of Liverpool Street] quite convinced that he had lost £20 not £10’.[20]

Hobart General Hospital records show that in 1926 Tom Stacey had sutures inserted in a cut in his face sustained while fighting at Adamsfield.[21] His alcohol-fuelled lifestyle is easily traced today through digitised newspapers. Whatever money he made was soon spent, and he became the epitome of the old diehard prospector. In 1950 Tom Stacey was described as a 73-year-old ‘hermit’ living in a one-room shanty in the bush near Coles Bay, with only a dog for company. That dog hunted kangaroo meat, Old Tom had apple and cherry trees and grew vegetables to sell to guests at the nearby Coles Bay guesthouse. His bed was ‘a piece of sacking spread with fern’, and his ancient trousers were held together only by pieces of wire.[22] He was killed when hit by a car on the Tasman Highway near Sorell in 1954.[23]

Jim Stacey continued to prospect almost until his death in 1937.[24] In 1935, for example, when he was 78 years old, he and two of his sons were paid by the government to spend ten weeks prospecting the Hastings–Picton River area.[25] He died in the company of family and was remembered for his public service, not the least of which was leading the way to Adamsfield, where some gained a start in life and others scraped a living through the Great Depression. Stacey Street, Adamsfield, is overgrown by bracken fern, and Staceys Lookout on the Sawback Range, unvisited, but the twisted landscape of the mining field still recalls his skills, perseverance and vision.

[1] Birth record no.1518/1886.

[2] ‘Sudden death at Thomas Plains’, Launceston Examiner, 29 May 1878, p.2.

[3] RJ Stacey, ‘Exploring for minerals’, Mercury, 8 December 1907, p.6.

[4] The marriage on 18 February 1886 was registered at Emu Bay, no. 1266/1886.

[5] Birth record no.1687/1877.

[6] ‘Family notices’, Mercury, 2 June 1906, p.1.

[7] ‘The recruiting scheme’, Daily Post (Hobart), 17 February 1917, p.7; ‘Workers’ Political League’, Mercury, 21 December 1916, p.5.

[8] For the death of John Stacey, see ‘Tasmania: Nubeena’s avenue of honour’, Mercury, 5 November 1918, p.6. William Stacey joined E Company, in the New Zealand Army (see Nominal Roll, no.62, p.19, 1917). For his death see ‘Roll of honour: Tasmanian casualties’, Examiner, 12 November 1918, p.7. Thomas Albert Stacey and Robert Stacey were both wounded twice in France. Robert was also shell shocked.

[9] John Hutton to Sergeant Ward, 2 September 1916, SWD1/1/713 (TAHO).

[10] Note added to Police Gazette (Hobart), 12 January 1917, p.10.

[11] ‘Osmiridium: reported discovery’, Advocate, 8 September 1924, p.2.

[12] ‘Register of osmiridium buyers’ returns of purchases, September 1922–October 1925’, MIN150/1/1 (TAHO).

[13] ‘Mining reward: discovery of osmiridium’, Examiner, 20 December 1934, p.7.

[14] PB Nye, The osmiridium deposits of the Adamsfield district, Geological Survey Bulletin, no.39, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1929, p.3.

[15] ‘Osmiridium: Tasmania’s unique position’, Mercury, 29 September 1925, p.9.

[16] ‘Romance of Adams River’, Examiner, 25 December 1925, p.5.

[17] ‘Register of osmiridium buyers’ return of purchases’.

[18] For the trials and tribulations of Edith Stacey and her four children, see file SWD1/1/713 (TAHO). For Tom Stacey’s battles with liquor laws, see, for example, ‘Police Court news’, Mercury, 13 August 1927, p.3. Convicted of sending a child to buy alcohol for him, Stacey took six years to pay the small resulting fine (Police Gazette, 6 October 1933, p.204).

[19] Bert Farquhar, Bert’s story, Regal, Launceston, 1990, p.3.

[20] Horace Arnold ‘Jimmy’ Lane, I had a quid to get, the author, Stanley, 1976, p.63.

[21] ‘Register of applications for treatment, Outpatients Department’, Hobart General Hospital, 11 September 1926, HSD130/1/3 (TAHO).

[22] ‘A solitary bushman’, Examiner, 16 September 1950, p.7.

[23] ‘New clue found to hit-run motorist’, Mercury, 25 August 1954, p.5.

[24] Nubeena’, Mercury, 5 January 1938, p.9.

[25] See file AB964/1/1 (TAHO).

by Nic Haygarth | 09/07/17 | Tasmanian high country history

‘Mulga Mick’ O’Reilly (standing) and friend at Adamsfield, courtesy of the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

He was Irish, he was a dyed-in-the-wool member of the Labor Party, and he was a socialist. Those are things we can say with certainty about the ‘voice of Adamsfield’, ‘Mulga Mick’ O’Reilly. Beyond that, a lot of his life is open to debate. This well-travelled digger wrote two books, The Pinnacle Road and other verses (1935), which was a collection of his poems, most of them from his Tasmanian days, and the autobiography Bowyangs and boomerangs: reminiscences of 40 years’ prospecting in Australia and Tasmania (1944).

How reliable were they? Mick’s son John O’Reilly recalled his aunts saying that Bowyangs and boomerangs was mostly fabrication. In it he claimed tragic beginnings. Having been born at Shinrone, County Offaly, Ireland, in 1879, he lost his first wife and two sons in an influenza epidemic before coming to Australia. [1]

One of the things that makes it hard to keep track of ‘Mulga Mick’ is his way of acquiring other people’s memories. He loved to compose stirring poetry. He wrote as if he was the spirit of mineral prospecting, speaking for all the diggers. One of his efforts, ‘The men of ‘93’, was written about times on the Western Australian goldfields he probably never experienced. Perhaps he recorded the stories of old diggers, and then, like a true dramatist, he gave these immediacy by writing them up in the first person.

The Whyte River Hotel besieged by motorcyclists, probably in the 1920s. JH Robinson photo courtesy of the late Nancy Gillard.

In 1933 he wrote a lament for the Whyte River Hotel, which was the watering hole for the Nineteen Mile osmiridium field west of Waratah. The pub burnt down in 1929—and O’Reilly probably never laid eyes on it. Yet he described it with the utmost intimacy. Reading his poem, you would swear he had tied one with Jim McGinty, Tom Rouse, Sammy Dwyer and all the other veterans of the field. Even ‘old Burly Lynch’ the publican, lining the drinks up on the bar, got a run. Yet Lynch surrendered the licence of the Whyte River Hotel in 1912, many years before O’Reilly arrived in Tasmania.[2]

Likewise, ‘The Adams River Rush’ described an event he hadn’t attended.[3] The rush occurred in the spring of 1925. He was certainly at Adamsfield in 1928, and through the Great Depression years, the toughest times on that osmiridium field. During these years he delivered missives from the diggings that captured many facets of the experience—the longing for loved ones and the comforts of town; the misery of stirring from a warm bed to work in the mud; comic arguments and drunken fist fights; and the general scrap to make money and hang on to it.

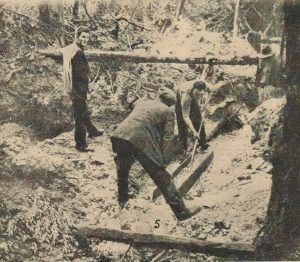

‘Mulga Mick’ (at right) trucking ore to the bin tip, with harry Hill and James Harrison, from the Tasmanian Mail, 13 January 1932, p.35.

Life was very simple for O’Reilly. The world was divided into ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’, that is, the parasite (the master) and the exploited (the servant). O’Reilly spelt ‘Digger’ with a capital ‘D’, whether that be the diggers of Adamsfield or the diggers of Gallipoli, because to him they were of the same manly ilk. All politicians were parasites who took the food from children’s mouths.[4] Miners’ wives and Adamsfield bush nurses were angels.[5] The press was also parasitic and should be ‘cleared from the face of all lands’, except, presumably, when newspapers bore his own copious contributions.[6] His penmanship was fluent, eloquent and often sympathetic to the down-trodden and forgotten, like the ‘heroes’ of Gallipoli, the elderly, the poor.[7] O’Reilly saw the Adamsfield osmiridium field as the epitome of the worker’s struggle for survival with dignity. He urged the workers to strike a blow for freedom against ‘pampered parasites [stealing] our children’s bread’, citing a particularly pathetic example of a large, young family forced to trudge out to the remote diggings.[8] ‘Out latest hospital: is not finished yet’, published in Hobart newspaper the Voice in 1931, was a protest about poor public infrastructure. Adamsfield was in the ridiculous situation of having a hospital with no bathroom, patients having to bathe in a passing water race:

‘When the smoke goes curling through the hole

Where the chimney ought to be,

And the old black billy on the fire

To make the evening tea;

When the hurricane lamp is lighted up,

Then you can safely bet,

It looks more like a Digger’s Camp

That is not finished yet.

If a patient ever gets a bath,

It’s on the instalment plan,

With just a little drop each day

From out the billy-can.

He rubs himself both her and there

Till he is partly wet:

Some day he may get over all,

For the bathroom’s not finished yet.’[9]

There was plenty of humour in his verse. When Jack Brennan claimed to have found a lode of osmiridium, O’Reilly predicted that it would only bring him enough money to buy a new commode.[10] In ‘The lady dentist’s visit to Adamsfield’ he described the anticipation of some rare female attention when Hobart dentist Olive Shepherd decided to make a business call to the diggings:

‘Some developed toothache that had never had a tooth

Since their father’s hairy lug they used to bite,

Another one’s got gumboils all around the ancient root

Of the one and only molar that’s in sight …

Not for years can we remember when excitement ran so high,

Or a ‘shepherd’ caused such stir among the sheep.

Now the old and toilworn Diggers wear a collar and a tie,

It’s enough to make the blooming angels weep.’[11]

However, O’Reilly’s pet plan to increase digger prosperity and extend the life of the osmiridium field was deadly serious. He wanted the government to fund a scheme to drain about 1000 acres of swampy flats along the Adams River which he claimed he had already tested successfully for metal. Without producing a single assay report as evidence, he claimed this would return about £200,000-worth of osmiridium.[12] The idea was to drain the area by way of a deep tail race terminating at the Adams River Falls, although others hit upon a more radical plan to blast away the falls themselves, thereby increasing the river flow. Asked to report on the scheme in 1931, Government Geologist PB Nye claimed that the area which would benefit from drainage was at most 667 acres and that insufficient work had been done to prove that the ground in question contained payable osmiridium—let alone osmiridium that would justify an outlay of anything up to £10,000 on such a tail race.[13]

O’Reilly retired to Glenorchy, took a job as a labourer building the Pinnacle Road up Mount Wellington, above Hobart, and continued to fire off instructions for a better world. St Peter probably copped an earful as ‘Mulga Mick’ stormed the Pearly Gates.

[1] MJ O’Reilly (‘Mulga Mick’), Bowyangs and boomerangs: reminiscences of 40 years’ prospecting in Australia and Tasmania, Hesperian, Carlisle, WA, 1984 reprint, p.160; John O’Reilly, ‘Mulga Mick; prospector, miner, author and poet: a lost father rediscovered’, Tasmanian Ancestry, December 2013, p.149.

[2] The old Whyte River Pub’, Advocate, 16 September 1933, p.8; reprinted in MJ O’Reilly, ‘Mulga Mick’, The Pinnacle Road and other verses, the author, Hobart, 1935, pp.62‒64. The Whyte River Hotel was never rebuilt.

[3] MJ O’Reilly, ‘Mulga Mick’, ‘The Adams River Rush’, The Pinnacle Road and other verses, pp.55–57.

[4] See, for example, ‘Mulga Mick’ (MJ O’Reilly), ‘Stealing the children’s bread: lesson of the Adamsfield Track’, Voice, 30 April 1932, p.7.

[5] For diggers’ wives and bush nurses as angels, see MJ O’Reilly, ‘Mulga Mick’, ‘The ossie diggers’ wives at Adamsfield’, in The Pinnacle Road and other verses, the author, Hobart, 1935, pp.28‒29; and ‘Sister’s sympathy’, Voice, 11 April 1931, p.6.

[6] For the ‘parasitic press’, see ‘Mulga Mick’ (MJ O’Reilly), ‘A poetic exchange’, Voice, 16 May 1931, p.2.

[7] See ‘Mulga Mick’ (MJ O’Reilly), ‘Armistice Day: “We’ll ne’er forget the price”’, Voice, 7 November 1931, p.1; and ‘Stealing the children’s bread: lesson of the Adamsfield Track’, Voice, 30 April 1932, p.7.

[8] ‘Mulga Mick’ (MJ O’Reilly), ‘Stealing the children’s bread: lesson of the Adamsfield Track’, Voice, 30 April 1932, p.7.

[9] ‘Mulga Mick’ (MJ O’Reilly), ‘Not finished yet’; quoted in ‘Our latest hospital’, Voice, 3 January 1931, p.2.

[10] ‘Jack Brennan’s osie [sic] lode’, poem signed ‘Mulga Mick’, dated 1929, and reprinted in CA Bacon, Notes on the mining and history of Adamsfield, Report, no.1992/20, Mineral Resources Tasmania, Hobart, 1992, p.8.

[11] MJ O’Reilly, ‘Mulga Mick’, ‘The lady dentist’s visit to Adamsfield’, The Pinnacle Road and other verses, pp.47–48.

[12] ‘Mulga Mick’ (MJ O’Reilly), ‘Osmiridium diggers’, Mercury, 2 September 1932, p.8; MJ O’Reilly, ‘Adamsfield development’, Mercury, 7 February 1933, p.6.

[13] PB Nye, ‘Proposal to drain the Adams River Flats by constructing a deep tail race at the Adams River Falls’, Unpublished Report, 76–79/1931, Department of Mines, Hobart, p.78; ‘Osmiridium’, Mercury, 16 January 1933, p.5.

by Nic Haygarth | 05/07/17 | Tasmanian high country history

The Adamsfield sly-grog shop was anything but sly—on the contrary, it was an open secret. Commonly known as ‘The Boozer’ and ‘The Miner’s Delight’, it functioned so long as there were thirsts to be quenched, livelihoods to be drowned and punches to be thrown. For two decades it was the toast of south-western Tasmania. The greatest bottle dump in south-western Tasmania attests to osmiridium diggers’ habit of pissing their winnings away.

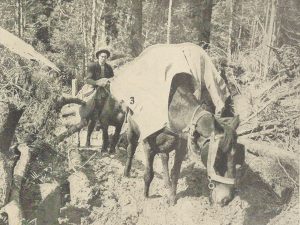

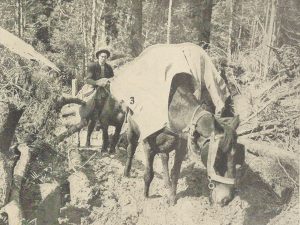

A pack-horse team on its way from Fitzgerald to Adamsfield – all the liquor was brought in surreptitiously. From the Tasmanian Mail, 23 September 1925.

Control the liquor, and you control the town—or so the theory went. In the absence of police, church, bank and any moral authority apart from a committee formed by the diggers themselves, a licensed hotel was surely the key to controlling the reputedly 800- or 1000-man-strong Adams River osmiridium rush of 1925. So it was that in December of that year a licence was granted to well-known publican Eldon Joseph. Lot 10 in the newly surveyed township of Adamsfield was set aside for his establishment, but it burned down during construction and never opened.[1] In its place, Bernie ‘Saviour’ Symmons, as he was known, built a billiard room and sly-grog shop which occupied Lots 9 and 10. Symmons’ partner was Ralph Langdon, and there was a bit of history between them. Langdon had previous convictions for running Hobart gaming houses, including one with Symmons.[2] When the Adams River rush began the pair first operated a ‘refreshment’ hut—that is, a sly-grog and accommodation house known as ‘The Digger’s Rest’—as the first staging post along the 42-kilometre track.[3] Gladys Langdon was the cook and manager there.[4]

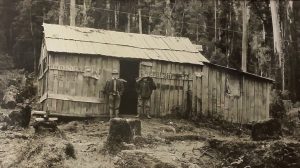

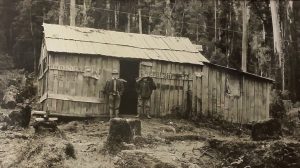

‘The Digger’s Rest’, the first Symmons and Langdon sly-grog shop on the Adamsfield Track, 1929. Cropped from NS1914-1-29, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

Now Symmons and Langdon were doing the same thing in Adamsfield itself. This establishment, known officially as Symmons’ Hall, was rocked by a bomb in June 1926. The device probably consisted of sticks of gelignite placed inside a jam tin under a bed, and such was the explosion that it rocked a diggers’ camp kilometres away at the Boyes River.[5] Most likely it was not a big job to rebuild ‘The Boozer’ after that, since it would only have been a large paling hut, and soon, inevitably, it was the scene of further ruckuses, fist fights and raids by visiting police.

The most celebrated altercation at ‘The Boozer’ was the one in which digger Arthur Blacklow had the end of his nose bitten off in a drunken brawl, a case which played out as a grievous bodily harm charge in the New Norfolk Police Court. The alleged nose biter was acquitted after a piece of proboscis in a bottle was presented as evidence. Blacklow chose this time to reveal that he could not recognise his own nose:

‘He could not … say that the flesh in the bottle was the piece of nose he gave to the sister [Nurse Johnson, the Adamsfield bush nurse]. The piece given to the sister would be bigger.’[6]

Symmons and Langdon remained partners until 1930, when both left the field. Remarkably, neither was ever busted for selling liquor without a licence. ‘Remarkably’ refers in particular to a 1926 raid on the two buildings that sat on Lots 9 and 10. Sergeant Arnol entered the building on Lot 10, which appears to have been an alcohol warehouse, something akin to a Russian supermarket. Inside he found

- 26 bottles of brandy

- 30 half flasks of brandy and whisky

- 15 bottles of Schnapps

- 1 case of gin

- 1 case of brandy

- 8 bottles of gin

- 8 bottles of ‘special’ whisky

- 13 bottles of rum

- 50 flasks of gin and Schnapps

- 3 bottles of ale

- boxes consigned to R Langdon, Fitzgerald

Arnol charged John Holder, who was on the premises, with selling liquor without a licence, but he could not prove that Holder was the owner of the premises.

Sergeant Arnol also went next door to the building on Lot 9, where he found Ralph Langdon, plus a counter with 14 empty beer glasses on it, a bottle of gin, a bottle of rum, a 9-gallon cask of beer and other empty casks. He charged Langdon with selling liquor without a licence. However, because the premises were registered in the name of Bernie Symmons, the charge could not be sustained.[7] Failure to convict in the face of overwhelming evidence probably did nothing for Arnol’s career prospects.

Ralph Langdon’s story has other priceless elements. One is that when he sold his business in Adamsfield he got into an argument with the buyer, John Gladstone, and the sale of a sly-grog shop ended up being adjudicated on in the Supreme Court in 1931.[8] The second is that Langdon put his takings from his Adamsfield business into buying the lease of the Wheatsheaf Hotel in Hobart.[9] Did he wow the Licensing Board with ossie field testimonials?

Langdon’s successors in the Adamsfield sly-grog trade, John Gladstone and Elias Churchill, were both nabbed for selling liquor without a licence at ‘The Boozer’ in 1930.[10] Churchill followed Langdon by becoming a Hobart publican. In 1934 Langdon had the Wheatsheaf and Churchill had the Duke of York.[11] William Francis Powell, an old Victorian digger who had come to Adamsfield via Savage River, replaced them in the senior apprentice position at ‘The Boozer’. Powell’s sly-grog shop, which slowly disintegrated among the bracken ferns after his death in 1946, is still marked by an impressive bottle dump—last resting place of ‘The Miner’s Delight’, or the true ‘bank’ of Adamsfield.[12]

[1] ‘Hotel for Adams Field [sic]’, Mercury, 10 December 1925, p.10.

[2] ‘Successful police raid’, News (Hobart), 6 January 1925, p.3.

[3] ‘The “Ossy” field’, News, 5 November 1925, p.1

[4] ‘Whose property?’, Mercury, 1 December 1933, p.6.

[5] ‘Sensation at Adamsfield’, Mercury, 3 June 1926, p.6; ‘Adamsfield: the recent bombing case’, Mercury, 9 June 1926, p.9.

[6] ‘Adamsfield affray’, Mercury, 19 November 1931, p.2.

[7] ‘Alleged sly-grog selling’, Mercury, 8 January 1927, p.2. ‘Registered’ does not refer to holding a liquor licence. Under the various Crown Lands Acts, a residence licence could be obtained to take possession of and occupy up to a quarter of an acre of land.

[8] ‘Supreme Court’, Mercury, 16 September 1931, p.11.

[9] ‘Whose property?’, Mercury, 1 December 1933, p.6.

[10] ‘Sly grog at Adamsfield’, Advocate (Burnie), 30 June 1930, p.5.

[11] ‘Licensing Courts’, Mercury, 29 October 1934, p.2.

[12] ‘Family notices’, Mercury, 9 March 1946, p.10.

by Nic Haygarth | 16/06/17 | Tasmanian high country history

John Baptiste (left), a female visitor and a fellow digger at camp, Savage River, in 1924. Fred Smithies photo, NS573-4-4-1, Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office.

John Baptiste, aka Hooky Jack, hides his metal hook hand, Savage River, 1924. Fred Smithies photo, NS573-4-2, TAHO.

Old Hooky was no new chum—

All his life he’d chased the gold.

And judging by his ‘skiting’

Won—and squandered—wealth untold.

He’d chased it in the Yukon,

In Alaska’s ice and snow,

And north from hot Coolgardie

Where the toughest only go.[1]

The toughest also tackled Tasmania, chasing osmiridium, and that’s where ossie digger Henry Humphries penned these words about his old mate ‘Hooky Jack’. The one-armed prospector, born as John D’Ahren Baptiste, spent at least three decades on Australian shores chasing everything that glittered. And he had a way of finding it:

A lucky man was Hooky and,

In truth, no matter where

He sank the most unlikely hole

There’d be some ‘metal’ there.[2]

Luck or skill? I fancy the latter. You don’t storm goldfields without learning the how, where and why of finding precious metals.

But who was Hooky Jack, and where did he come from? He is said to have inherited the equivalent of £30,000 ($60,000) in his home town of Madeira, Portugal, back in the 1880s, before embarking on his tour of world goldfields.[3] Perhaps squandering his inheritance was the start of a dissolute life, a rollicking refrain of tramp steamers, bars, brothels and all the trappings of the wild west.

It seems unlikely that Baptise made a fortune on Australian gold or Tasmanian osmiridium, although, admittedly, he is a hard man to track on local soil. Prospectors of a century ago often managed to elude electoral rolls, censuses and other public records. Although ships’ logs, gazetted mining leases and court cases are the historian’s allies, the John Baptistes of Australia take some sorting. Newspapers of his day bore so many references to the biblical John the Baptist, to St John the Baptist churches, guilds, fetes, lodges and French statesmen that following the prospector’s life is a painstaking affair. He wasn’t John Baptiste the Portuguese sailor executed for murder at Perth in 1900.[4] Nor was he the Sydney nurseryman John Baptist, and as for the Parisian sausage maker and confectioner from Wagga Wagga … let’s just say that these would be surprising career moves for a carousing wastrel.[5]

Happily, John D’Ahren Baptiste had some distinguishing characteristics which aid identification. One was his love of rum, another the colour of his skin. Baptiste was referred to as a ‘coloured gentleman’ and a ‘half caste’. There was hilarity in a North Melbourne courtroom when in 1895 he was summoned to answer a paternity suit. Baptiste’s defence submitted that the complainant, Annie Boddington, had no proof that he was the father of her newborn. Boddington’s response was to produce the dark-skinned infant, shouting, ‘Haven’t I! He’s a black man—and there’s no mistake about this lot’. The judge seems to have accepted this rather flimsy ‘evidence’, ordering Baptiste to pay maintenance.[6]

Baptiste’s most distinctive trait was his hook. Various prosthetics led the way on the osmiridium fields. ‘Peg Leg Ted’ Loughnan climbed Mount Stewart on one good leg to peg a reward claim in 1917.[7] Lost Adamsfield schoolteacher Tom Cole was tracked along the Gell River by indentations left in the soil by his wooden leg in 1938.[8] It helped carry him into eternity. Baptiste’s metal hook beat those wooden legs for versatility. It raked the fire, served as a fork in food preparation and hoisted the billy from the hot coals. He could saw with it, swing a pick and chop with it.[9] In a brawl he was even said to have used his hook as a club.[10]

Exactly how or when he lost his hand is unknown. Certainly he had the hook during his time on the Gippsland goldfields, Victoria, during the early 1900s.[11] Max Dyer described Baptiste as

‘probably the best miner to ever sluice gold along the Mitta Mitta. Folks used to say that Hookey [sic] could smell gold, as he was never known to have a useless claim. He had a drinking problem as well, and my mother had often told me of Hookey waving his hook in the air and cursing all and sundry … when he was in town on a bender. This only happened occasionally and when he was working his claim he gave it his undivided attention’.[12]

Yes, Hooky Jack knew his business and had plenty of nous. This was apparent when he arrived on the Nineteen Mile Creek osmiridium field nineteen miles west of Waratah. In 1914 stockpiling caused a dramatic slide in the osmiridium price, so he stashed nineteen ounces at the Waratah Post Office and returned to Gippsland, where he registered the Hard to Seek gold claim.[13] Negotiations over sale of that osmiridium stash continued while he was in New Zealand 1916–17, and he probably disposed of it in 1918 when the price almost doubled.[14]

With Russia engulfed in civil war, Tasmania suddenly had a world monopoly on the point metal osmiridium used to tip the nibs of gold fountain pens. Baptiste hit the new Mount Stewart ossie field in the foothills of the Meredith Range. Later he tried Savage River, working firstly with Harry Stanley, then with Charles Connors. His partnership with the latter ended in 1923 after the Portuguese spent nineteen days in the Waratah Hospital recovering from several blows to the head with a vase.[15]

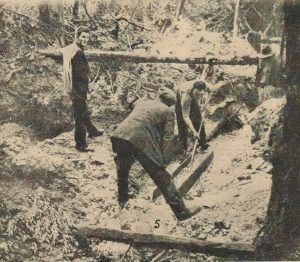

John Baptiste (back to camera) working a sluice box for osmiridium at Keep it Dark Gully, Adamsfield. From the Tasmanian Mail, 11 November 1925, p.40.

Baptiste fared better with former policeman Percy Marsh. The pair was among the first diggers to follow the Stacey parties to the Adams River osmiridium field in June 1925. There the Adamsfield poet ‘Mulga Mick’ O’Reilly claimed to have found Baptiste doing so well that he employed two men: one carried his stores in from the Florentine River, while another ‘did his cooking, fetched his whisky from the sly-grog shop, and put him to bed at night’. One report was that he sold his claim for a bottle of rum.[16] Another had Baptiste making £8000 in three months with Marsh at Keep it Dark Gully—a sly reference to his skin colour?—before selling the claim for £350.[17] Again, however, rum may have been his downfall, as he claimed to have been robbed of £200 of his winnings in Hobart in December 1925.[18] Perhaps this is what caused him to default on payments for a block of land at Prince of Wales Bay, Glenorchy, in 1927, losing his investment.[19] By then Hooky Jack was back on the west coast, prospecting for tin in the Norfolk Range.[20]

Baptiste was done with the ossie, but what happened to his winnings? Was it a case of easy come, easy go in a string of Hobart pubs and brothels? And what happened to him? He was not the supposed 64-year-old Frenchman John Baptiste who died at Broken Hill in 1938.[21] Nor did he go missing on the Great Depression gold trail like Harry Bell Lasseter. Baptiste appears to have seen out his days prospecting for gold in Gippsland, a naturalised Australian who passed the age of 80.[22] Perhaps, like Sammy Dwyer, last man at the Nineteen Mile, he was content to scrape a subsistence living from an old field he knew well, cooking in a camp oven, growing a few vegetables and reading about a world that had passed him by.

[1] Henry Humphries, ‘Hooky Jack’; poem printed in the Advocate (Burnie), 31 March 1962, p.13.

[2] Henry Humphries, ‘Hooky Jack’; poem printed in the Advocate (Burnie), 31 March 1962, p.13.

[3] ‘Along the “ossy” track’, News (Hobart), 10 September 1925, p.1.

[4] ‘The Ethel mutiny and murders’, West Australian (Perth), 18 June 1900, p.2.

[5] See, for example, ‘Progress of the suburbs’, Sydney Morning Herald, 21 February 1914, p.8; and advert, Wagga Wagga Express, 15 August 1895, p.4.

[6] ‘A black bit of evidence’, Age (Melbourne), 18 October 1895, p.6.

[7] For Loughnan’s application for a monetary reward for his and Stanton’s discovery, see Edward Loughnan to Sir Elliott Lewis 23 December 1920, AB948/1/98 107B ‘Correspondence: osmiridium’ (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, Hobart).

[8] ‘Feared that missing prospectors have been drowned’, Advocate, 17 June 1938, p.6.

[9] Henry Humphries, ‘Hooky Jack’; poem printed in the Advocate, 31 March 1962, p.13.

[10] ‘Waratah assault case’, Advocate, 19 November 1923, p.5.

[11] The Commonwealth of Australia electoral rolls for 1903, 1908 and 1909, State of Victoria, Division of Gippsland, roll of electors for the Subdivision of Omeo, described John Baptiste as a miner at Mitta Mitta. In 1911 his 30-acre gold lease on the Bemm River, Gippsland, was gazetted as abandoned (‘Gazette notifications’, Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle (Victoria), 2 September 1911, p.2). He was naturalised on 29 November 1911 at the age of 49, Victoria, Index to naturalisation certificates, no.12861, https://www.ancestry.com.au/interactive/60711/44441_346529-02210?pid=16656&backurl=http://search.ancestry.com.au/cgi-bin/sse.dll?_phsrc%3DAEX134%26_phstart%3DsuccessSource%26usePUBJs%3Dtrue%26gss%3Dangs-g%26new%3D1%26rank%3D1%26gsfn%3Djohn%26gsfn_x%3DNIC%26gsln%3Dbaptista%26gsln_x%3DNN%26msbdy%3D1865%26msbpn__ftp%3DPortugal%26msbpn%3D5184%26msypn__ftp%3DMelbourne,%2520Victoria,%2520Australia%26msypn%3D97862%26cpxt%3D1%26cp%3D2%26MSAV%3D1%26MSV%3D0%26uidh%3D2l5%26pcat%3DROOT_CATEGORY%26h%3D16656%26recoff%3D6%25208%26dbid%3D60711%26indiv%3D1%26ml_rpos%3D1&treeid=&personid=&hintid=&usePUB=true&_phsrc=AEX134&_phstart=successSource&usePUBJs=true, accessed 17 June 2017.

[12] Max Dyer, Hot air, bee stings & echoes: more bush yarns, the author, Bairnsdale (Victoria), 2006, pp.5 and 49.

[13] HB Silberberg to Bert Osborne, 8 May 1914, File 64-2-14, HB Selby & Co Papers (Noel Butlin Business Archive, Canberra); advert, Snowy River Mail (Orbost, Victoria), 11 December 1914, p.2.

[14] HB Selby to John Baptiste, 14 December 1916 and 19 January 1917, File 64-2-17, HB Selby & Co Papers (Noel Butlin Business Archive, Canberra);

[15] ‘Waratah assault case’, Advocate, 19 November 1923, p.5.

[16] MJ O’Reilly (‘Mulga Mick’), Bowyangs and boomerangs: reminiscences of 40 years’ prospecting in Australia and Tasmania, Hesperian, Carlisle (Western Australia), 1984 reprint, p.160.

[17] ‘The sifting out’, Examiner, 25 December 1925, p.5; ‘Adams River osmiridium field’, News (Hobart), 9 September 1925, p.1.

[18] ‘The morning after’, Daily News (Perth), 30 December 1925, p.1.

[19] Advert, Mercury, 16 November 1927, p.12.

[20] ‘Reported missing: prospector returns to camp, Mercury, 29 July 1927, p.6.

[21] ‘Wilcannia-Forbes Diocese’, Catholic Press, 22 September 1937, p.27.

[22] The Commonwealth of Australia electoral rolls for 1931, 1934 and 1943, State of Victoria, Division of Gippsland, roll of electors for the Subdivision of Leongatha, described John A Baptista as a prospector at Walkerville, via Fish Creek.

by Nic Haygarth | 04/04/17 | Tasmanian high country history

More like a manicurist than a miner: Louise Lovely as Dick Fleetwood (right) and Gordon Collingridge as Salarno (left) in the 1925 movie Jewelled nights. JH Robinson photo courtesy of the late Nancy Gillard.

In November 1922 Nineteen Mile Creek osmiridium digger Charlie Prouse slapped a record-breaking lump of metal on the bar of Bischoff Hotel in Waratah, the nearest town. Prouse’s sale of his father Tom’s all-time-Tasmanian-record nugget probably brought them much needed, instant cash—and paid off their tab.

Metal as frontier currency fed into the old gold rush romance of a roistering wild west. This image and the rugged landscape appealed to Hobart romance writer Marie Bjelke Petersen, who found ‘nuggets’ of a different kind—human ones—on the ‘ossie’ fields. Some of her nuggets were female. In her best-selling 1923 novel Jewelled nights, gender bending on the Savage River osmiridium field enabled a Melbourne society belle to evade a marriage of inconvenience.[1] The runaway bride, Elaine Fleetwood, hid out on the Tasmanian frontier in the guise of a man, Dick Fleetwood. When, eventually, her clever disguise of slicked-down hair and dungarees failed her, the heroine submitted to fellow digger Larry Salarno, nature’s true gentleman. They married in nature’s own cathedral, a beautiful button grass area known as Long Plain, which today, unfortunately, is not quite so romantic, being occupied by the settling ponds of the Savage River iron ore mine.[2]

Bjelke Petersen was already a best-selling author when she wrote Jewelled nights. The irony of gushing heterosexual romance peddled by an unmarried virgin with a live-in female companion seems to have been lost on swooning young female fans across the English-speaking world. In the course of her research, Bjelke Petersen had established a reputation for venturing into the masculine realm at the frontier of civilisation. In 1921 she and her companion Sylvia Mills took a grand tour of the western mining fields. Based at the Whyte River Hotel, and with Vic Whyman as their guide, they had many thrilling experiences while visiting the Rio Tinto (Savage River bridge), Burnt Spur and Nineteen Mile osmiridium fields.[3] Bjelke Petersen gushed that

‘we often wondered if we should ever return. The precipitous mountain tracks were so dangerous, snakes were most numerous, we had to drive with horses that had never been in harness before, and were out in thunderous storms of tropical severity …’

She claimed that on one occasion, only the intervention of Joe O’Connor, manager of the Jasper mine, saved the pair from being backed off the edge of a mountain track by a frightened horse during a storm. While crossing Long Plain en route to Burnt Spur, the author was struck by

‘the most gorgeous forests of giant myrtles and sassafras, the densest in the world, with alluring fern gullies and trickling streams, all along the five miles of awe-inspiring grandeur till the river was reached, deep down in the heart of a huge ravine’.[4]

Members of the Humphries family, Rendelsham, South Australia, 1905, including four future osmiridium diggers: the amateur poet Henry (back row, second from left), Allan (standing, extreme left), Bob (standing, extreme right) and Frances Hazel (aka Frank, the girl in the centre of the front row). Photo courtesy of the late Olive Plapp.

Frances Hazel Humphries (in wide-brimmed hat) as a young woman. Crop from a Stephen Hooker photo courtesy of Phil Rolton.

Frank Humphries as a man (standing, at left), 1932. Crop from a photo courtesy of the late Olive Plapp.

At Burnt Spur, where her novel was later set, she met one of the osmiridium field’s two women, Eva Tudor. A local legend, however, preferred another local, Frances Hazel Humphries, as the model for Bjelke Petersen’s heroine Elaine Fleetwood.[5] Humphries, born a girl and known by her middle name Hazel, eventually took a male name, wore men’s clothes, and performed traditionally male labour—including a stint on the Mount Stewart osmiridium field. Former Waratah resident Eric Thomas believed that as a young woman Hazel fell pregnant and, after having the baby at a Salvation Army maternity home, returned to Waratah as Frank Humphries, with hair brushed back and wearing a felt hat. He milked cows for the Penney family and delivered the milk by cart around Waratah. Thomas remembered that after a short stint working at Mrs Delphin’s ‘eat up shop’ in Waratah, Frank tried his hand at the osmiridium fields. It was there that Thomas met him while packing supplies for Tom Cumming and Ray Whyman.[6] In his book Taking you back down the track, Humphries’ contemporary Harry Reginald Paine recalled his ability with horses, cross-cut saw and pick and shovel.[7] In the years 1926‒31 Frank Humphries was an employee of the Burnie Dairy Co.[8] Later he became a Burnie shopkeeper, and ‘married’ a female partner with whom he relocated to Melbourne.

There were female diggers and miners’ partners on several osmiridium fields. Frank–Hazel’s story is more unusual yet, but there is no evidence of it being the inspiration for Marie Bjelke Petersen’s romance. It is unknown whether Bjelke Petersen even met Humphries. Yet one can imagine the novelist admiring a woman who refused, as Bjelke Petersen did herself, to conform to a prescribed gender role. Career, social standing and much wider scrutiny would have prevented Bjelke Petersen venturing beyond this role in Hobart—but the western mining fields, as the author found, offered a non-conformist almost anonymity. Perhaps that discovery was the real inspiration for Jewelled nights.

[1] Marie Bjelke Petersen, Jewelled nights, Hutchinson & Co, London, 1923.

[2] Button grass (Gymnoschoenus sphaerocephalus) is a native Tasmanian sedgeland plant so named because of its button-like seed heads.

[3] Vic Whyman claimed he was the singing coach driver who was immortalised in Jewelled nights. See Maggie Weidenhofer, ‘Marie Bjelke Petersen: forgotten writer of passion’, This Australia, Spring 1983, p.42.

[4] ‘In the wilds of the west’, Advocate, 29 January 1921, p.3.

[5] See Harry Reginald Paine, Taking you back down the track … is about Waratah in the early days, Somerset, 1994, p.98.

[6] Letter from Eric Thomas, undated, 1990s. The 1919 and 1924 assessment rolls show H Humphries occupying a cottage in North Street owned by HP McCreery (Tasmanian Government Gazette, 10 November 1919, p.2122; and 24 November 1924, p.2280).

[7] Harry Reginald Paine, Taking you back down the track … is about Waratah in the early days, Somerset, 1994, p.98.

[8] ’15 witnesses examined yesterday’, Advocate, 2 September 1931, p.6.