When 52-year-old Maria Francis died of heart disease at Middlesex Station in 1883, Jack Francis lost not only his partner and mother to his child but his scribe.[1] For years his more literate half had been penning his letters. Delivering her corpse to Chudleigh for inquest and burial was probably a task beyond any grieving husband, and the job fell to Constable Billy Roden, who endured the gruesome homeward journey with the body tied to a pack horse.[2]

By then Jack seems to have been considering retirement. He had bought two bush blocks totalling 80 acres west of Mole Creek, and through the early 1890s appears to have alternated between one of these properties and Middlesex, probably developing a farm in collaboration with son George Francis on the 49-acre block in limestone country at Circular Ponds.[3]

Here Jack took up with the twice-married Mary Ann (real name Sarah) Wilcox (1841–1915), who had eight adult children of her own.[4] Shockingly, as the passing photographer Frank Styant Browne discovered in 1899, Mary Ann’s riding style emulated that of her predecessor Maria Francis (see ‘Jack the Shepherd or Barometer Boy: Middlesex Plains stockman Jack Francis’). However, Mary Ann was decidedly cagey about her masculine riding gait, dismounting to deny Styant Browne the opportunity to commit it to posterity with one of his ‘vicious little hand cameras’.[5]

Perhaps Mary Ann didn’t fancy the high country lifestyle, because when Richard Field offered Jack the overseer’s job at Gads Hill in about 1901 he took the gig alone.[6] This encore performance from the highland stockman continued until he grew feeble within a few years of his death in 1912.[7]

Mary Ann seems to have been missing when the old man died. Son George Francis and Mary Ann’s married daughter Christina Holmes thanked the sympathisers—and Christina, not George or Mary Ann, received the Circular Ponds property in Jack’s will.[8] Perhaps Jack had already given George the proceeds of the other, 31-acre block at Mole Creek.[9]

By the time Mary Ann Wilcox died in Launceston three years later, George Francis had long abandoned the farming life for the high country. He was at Middlesex in 1905 when he renovated a hut and took part in the search for missing hunter Bert Hanson at Cradle Mountain.[10] Working out of Middlesex station, he combined stock-riding for JT Field with hunting and prospecting.

Like fellow hunters Paddy Hartnett and Frank Brown, Francis lost a small fortune when the declaration of World War One in July 1914 closed access to the European fur market, rendering his winter’s work officially worthless. At the time he had 4 cwt of ‘kangaroo and wallaby’ (Bennett’s wallaby and pademelon) and 60 ‘opossum’ (brush possum?). By the prices obtaining just before the closure they would have been worth hundreds of pounds.[11] Sheffield Police confiscated the season’s hauls from hunters, who could not legally possess unsold skins out of season.

The full list of skins confiscated by Sheffield Police on 1 August 1914 gives a snapshot of the hunting industry in the Kentish back country. Some famous names are missing from the list. Experienced high country snarer William Aylett junior was now Waratah-based and may have been snaring elsewhere.[12] Bert Nichols was splitting palings at Middlesex by 1914 but may not have yet started snaring there.[13] Paddy Hartnett concentrated his efforts in the Upper Mersey, probably never snaring the Middlesex/Cradle region. His double failure at the start of the war—losing his income from nearly a ton of skins, and being rejected for military service—drove him to drink.[14]

‘Return of skins on hand on the 1st day of August [1914] and in my possession’, Sheffield Police Station.

| Name | Location | Kangaroo/wallaby | Wallaby | Possum |

| George Francis | Msex Station | 448 lbs | 60 skins | |

| Frank Brown | Msex Station | 562 skins+ 560 lbs | 108 skins | |

| DW Thomas | Lorinna | 960 lbs | 310 skins | |

| William McCoy | Claude Road | 600 lbs | 66 skins | |

| Charles McCoy | Claude Road | 40 lbs | ||

| Geo [sic] Weindorfer | Cradle Valley | 31 skins | 4 skins | |

| Percy Lucas | Wilmot | 408 skins | 56 skins | |

| G Coles | Storekeeper, Wilmot | 5 skins | ||

| Jack Linnane | Wilmot | 15 skins | ||

| WM Black | Black Bluff | 50 skins | 3 skins | |

| James Perry | Lower Wilmot | 2 skins | 13 skins |

Most of those deprived of skins were bush farmers or farm labourers who hunted as a secondary (primary?) income, while George Coles was probably a middleman between hunter and skin buyer:

Frank Brown (1862–1923). Son of ex-convict Field stockman John Brown, he was one of four brothers who followed in their father’s footsteps (the others were Humphrey Brown c1855–1925, John Thomas [Jacky] Brown, 1857–c1910 and Richard [Dick] Brown). He appears to have been resident stockman at Field brothers’ Gads Hill Station in 1892.[15] Frank and Louisa Brown were resident at JT Field’s Middlesex Station c1905–17. He died when based at Richard Field’s Gads Hill run in 1923, aged 59, while inspecting or setting snares on Bald Hill.[16]

David William Thomas (c1886–1932) of Railton bought an 88-acre farm on the main road at Lorinna from Harry Forward in 1912.[17] His 1914 skins tally suggests that farming was not his main source of income—so the loss must have been devastating. Other Lorinna hunters like Harold Tuson were working in the Wallace River Gorge between the Du Cane Range and the Ossa range of the mountains.

William Ernest (Cloggy) McCoy (1879–1968), brother of Charles Arthur McCoy below, was born to VDL-born William McCoy and Berkshire-born immigrant Mary Smith at Sheffield.[18] He was the grandson of ex-convict John McCoy and the uncle of the well-known snarer Tommy McCoy (1899–1952).[19]

Charles Arthur (Tibbly) McCoy (1870–1962) was born to VDL-born William McCoy and Berkshire-born immigrant Mary Smith at Barrington.[20] He was the grandson of ex-convict John McCoy. Charles McCoy caught a tiger at Middlesex, depositing its skins at the Sheffield Police Office on 30 December 1901.[21] He was the uncle of the later well-known snarer Tommy McCoy.

Gustav Weindorfer (1874–1932), tourism operator at Waldheim, Cradle Valley, during the years 1912 to 1932. By his own accounts during 1914 he shot 30 ‘kangaroos’, eight wombats, six ringtails and one brush possum, as well as taking one ‘kangaroo’ in a necker snare.[22] While the closure of the skins market would have handicapped this struggling businessman, these skins would have been useful domestically, and the wombat and wallaby meat would have gone in the stew.

Percy Theodore Lucas (c1886–1965) was a Wilmot labourer in 1914, which probably means that he worked on a farm.[23] Nothing is known about his hunting activities.

George Coles (1855–1931) was the Wilmot storekeeper whose sons, including George James Coles (1885–1977), started the chain of Coles stores in Collingwood, Victoria.[24] George Coles bought TJ Clerke’s Wilmot store in 1912, operating it until after World War One. In 1921 the store was totally destroyed by fire, although a general store has continued to operate on the same site up to the present.[25] The five skins in George Coles’ possession had probably been traded by a hunter for stores. Coles probably sold them to a visiting skin buyer when the opportunity arose.[26]

John Augustus (Jack) Linnane (1873–1949) was born at Ulverstone but arrived in the Wilmot district in 1893 at the age of nineteen, becoming a farmer there.[27] Like George Francis, Linnane joined the search party for missing hunter Bert Hanson at Cradle Mountain in 1905, suggesting that he knew the country well.[28] His abandoned hunting camp near the base of Mount Kate was still visible in 1908.[29] Enough remained to show that Linnane was one of the first to adopt the skin shed chimney for drying skins.[30] He also engaged in rabbit trapping.[31] In 1914 he was listed on the electoral roll as a Wilmot labourer, but exactly where he was hunting at that time is unknown.[32]

Walter Malcolm (WM) Black (1864–1923) was a gold miner and hunter at the Lea River/Black Bluff Gold Mine in the years 1905–15. The son of Victorian grazier Archibald Black, WM Black was a ‘remittance man’, that is, he was paid to stay away from his family under the terms an out-of-court payment of £7124 from his father’s will.[33] He joined the First Remounts (Australian Imperial Force) in October 1915 by falsifying his age in order to qualify.[34] See my earlier blog ‘The rain on the plain falls mainly outside the gauge, or how a black sheep brought meteorology to Middlesex’.[35]

James Perry (1871–1948), brother of a well-known Middlesex area hunter, Tom Perry (1869–1928), who was active in the high country by about 1905. Whether James Perry’s few skins were taken around Wilmot or further afield is unknown.

No tigers at Middlesex/Cradle Mountain?

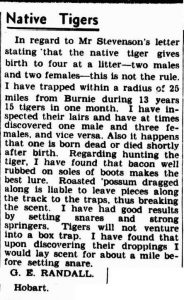

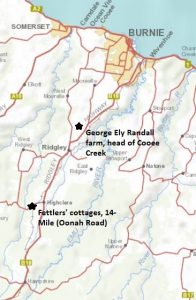

George Francis survived the financial setback of 1914. Gustav Weindorfer in his diaries alluded to collaboration with him on prospecting and mining activities, but they hunted in different areas. In 1919 Francis co-authored the three-part paper ‘Wild life in Tasmania’ with Weindorfer, which documented their extensive knowledge of native animals, principally gained by hunting them. At the time, the authors claimed, they were the only permanent inhabitants of the Middlesex-Cradle Mountain area, boasting nine years (Weindorfer) and 50 years’ (Francis) residency. They also made the interesting claim that the ‘stupid’ wombat survived as well as it did in this area because it had no natural predators, since the thylacine did not then and probably never had frequented ‘the open bush land of these higher elevations’.[36] While this suggests that George Francis had never encountered a thylacine around Middlesex, it’s hard to believe that his father Jack Francis didn’t, especially given the story that Jack’s early foray into the Vale of Belvoir as a shepherd for William Kimberley was tiger-riddled.[37] It’s also a pity the authors didn’t consult the likes of Middlesex tiger slayers Charlie McCoy (see above) and James Mapps—or rig up a séance with the late George Augustus Robinson and James ‘Philosopher’ Smith.

The dog of GA Robinson, the so-called ‘conciliator’ of the Tasmanian Aborigines, killed a mother thylacine on the Middlesex Plains in 1830.[38] Decades later, ‘Philosopher’ Smith the mineral prospector came to regard Tiger Plain, on the northern edge of the Lea River, as the most tiger-infested place he visited during his expeditions. It was popular among the carnivores, he thought, because the Middlesex stockman’s dogs by driving game in that direction provided a ready food source. ‘I thought it necessary’, he wrote about his experience with tigers,

‘to be on my guard against them by keeping a fire as much as I could and having at hand a weapon with which to defend myself in the event of being attacked by one or more of them … ‘[39]

Smith killed a female tiger on Tiger Plain and took its four pups from her pouch but found they could not digest prospector food (presumably damper, potatoes, bully beef, wallaby or wombat).[40] Philosopher’s son Ron Smith had no reason to doubt his father, as he found a thylacine skull on his property at Cradle Valley in 1913 which is now lodged in Launceston’s Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery.[41] There were still tigers in the Middlesex region at the cusp of the twentieth century. Like ‘Tibbly’ McCoy, James Mapps claimed a government thylacine bounty at this time, probably while working as a tributor at the Glynn Gold Mine at the top of the Five Mile Rise near Middlesex.[42]

George Francis in his will described himself as a ‘shepherd of Middlesex Plains’, yet he met his maker in the Campbell Town Hospital. His parents were dead and he had no remaining relatives. The sole beneficiary of his will was Golconda farmer and road contractor William Thomas Knight (1862–1938), probably an old hunting mate.[43] Francis’s job at Middlesex was filled by the so-called ‘mystery man’ Dave Courtney (see my blog ‘Eskimos and polar bears: Dave Courtney comes in from the cold’), whose life, as it turns out, is an open book compared to that of his elusive predecessor.

[1] Died 11 October 1883, death record no.167/1883, registered at Deloraine, RGD35/1/52 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=maria&qu=francis#, accessed 15 February 2020; inquest dated 13 October 1883, SC195/1/63/8739 (TAHO), https://stors.tas.gov.au/SC195-1-63-8739, accessed 15 February 2020. A pre-inquest newspaper reporter incorrectly attributed her death to suicide by strychnine poisoning (editorial, Launceston Examiner, 23 October 1883, p.1).

[2] It is likely that Jack Francis and Gads Hill stockman Harry Stanley conveyed Maria Francis’s body to Gads Hill Station, where Roden took delivery of it. See ‘A veteran drover’, Examiner, 7 March 1912, p.4; and ‘Supposed case of poisoning at Chudleigh’, Launceston Examiner, 13 October 1883, p.2. Later Roden had the job of removing Stanley’s body for an inquest at Chudleigh (Dan Griffin, ‘Deloraine’, Tasmanian Mail, 13 August 1898, p.26).

[3][3] For the land grant, see Deeds of land grants, Lot 5654RD1/1/069–71In 1890, 1892 and 1894 John and George Francis were both listed as farmers at Mole Creek (Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory, 1890–91, p.200; 1892–93, p.288; 1894–95, p.260). Jack Francis was reported to have left Middlesex in March 1885, being replaced by Jacky Brown (James Rowe to James Norton Smith, 10 March 1885; and to RA Murray, 24 September 1885, VDL22/1/13 [TAHO]). However, he appears to have returned periodically.

[4] She was born to splitter John Wilcox and Rosetta Graves at Longford on 17 July 1841, birth record no.3183/1847 (sic), registered at Longford, RGD32/1/3 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=sarah&qu=wilcox, accessed 14 March 2020; died 25 October 1915 at Launceston (‘Deaths’, Examiner, 8 November 1915, p.1). Mary Ann’s youngest child, Eva Grace Lowe, was born in 1879.

[5] Frank Styant Browne, Voyages in a caravan: the illustrated logs of Frank Styant Browne (ed. Paul AC Richards, Barbara Valentine and Peter Richardson), Launceston Library, Brobok and Friends of the Library, 2002, p.84.

[6] Wise’s Tasmanian Post Office directory for the period 1901–08 listed Jack Francis as an overseer at Gads Hill or Liena, while Mary, as she was described, was listed as a farmer at Liena, meaning Circular Ponds (1901, p.322; 1902, p.341; 1904, p.204; 1906, p.189; 1907, p.192; 1908, p.197).

[7] ‘A veteran drover’.

[8] ‘Return thanks’, Examiner, 2 March 1912, p.1; purchase grant, vol.36, folio 116, application no.3454 RP, 1 July 1912.

[9] Jack Francis bought purchase grant vol.18, folio 113, Lot 5654, on 25 November 1872. He divided it in half, selling the two lots on 6 May 1902 to Arthur Joseph How and Andrew Ambrose How for £30 each.

[10] ‘The mountain mystery: search for Bert Hanson’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 August 1905, p.3.

[11] 1 August 1914, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[12] See ‘William Aylett: career bushman’ in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, pp.42–43.

[13] See ‘Bert Nichols: hunter and overland track pioneer’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, p.114.

[14] See ‘Paddy Hartnett: bushman and highland guide’, in Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015, p.93.

[15] On 20 April 1892 (p.179) Frank Brown reported stolen a horse which was kept at Gads Hill, Deloraine Police felony reports, POL126/1/2 (TAHO).

[16] ‘Well-known stockrider’s death’, Advocate, 4 June 1923, p.2.

[17] ‘Lorinna’, North West Post, 28 August 1912, p.2; ‘Obituary: Mr DW Thomas, Railton’, Advocate, 21 April 1932, p.2.

[18] Born 21 March 1879, birth record no.2069, registered at Port Sorell, RGD33/1/57 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=william&qu=ernest&qu=mccoy. Accessed 10 April 2020.

[19] Born 26 June 1870, birth record no.1409/1870, registered at Port Sorell, RGD33/1/48 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=mccoy, accessed 15 September 2019; died 23 September 1962, buried in the Claude Road Methodist Cemetery (TAMIOT). For John McCoy as a convict tried at Perth, Scotland in 1792 and transported on the Pitt in 1811, see Australian convict musters, 1811, p.196, microfilm HO10, pieces 5, 19‒20, 32‒51 (National Archives of the UK, Kew, England).

[20] Born 26 June 1870, birth record no.1409/1870, registered at Port Sorell, RGD33/1/48 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=charles&qu=mccoy, accessed 15 September 2019; died 23 September 1962, buried in the Claude Road Methodist Cemetery (TAMIOT). For John McCoy as a convict tried at Perth, Scotland in 1792 and transported on the Pitt in 1811, see Australian convict musters, 1811, p.196, microfilm HO10, pieces 5, 19‒20, 32‒51 (National Archives of the UK, Kew, England).

[21] 30 December 1901, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[22] Gustav Weindorfer diaries, 1914, NS234/27/1/4 (TAHO).

[23] Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Wilmot, Subdivision of Kentish, 1914, p.27.

[24] ‘About people’, Age, 22 December 1931, p.8.

[25] ‘Fire at Sheffield [sic]’, Mercury, 8 November 1921, p.5.

[26] Coles held a tanner’s licence in 1914 (‘Tanners’ licences’, Tasmania Police Gazette, 1 May 1914, p.109), but the legal requirement was that skins had to be sold to a registered skin buyer. Despite this, plenty of people tanned and sold their own skins privately.

[27] ‘”Back to Wilmot” celebration’, Advocate, 12 April 1948, p.2.

[28] 10 July 1905, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[29] Ronald Smith, account of trip to Cradle Mountain with Bob and Ted Addams, January 1908, held by Peter Smith, Legana.

[30] Ronald Smith, account of trip to Cradle Mountain with Bob and Ted Addams, January 1908, held by Peter Smith, Legana.

[31] On 18 April 1910, Linnane reported the theft of 200 rabbit skins from his hut valued at £2, ‘Daily Record of Crime Occurrences Sheffield 1901–1916’, POL386/1/1 (TAHO).

[32] Commonwealth Electoral Roll, Division of Wilmot, Subdivision of Kentish, 1914, p.26.

[33] ‘Supreme Court’, Age, 27 February 1885, p.6.

[34] World War One service record, https://www.awm.gov.au/people/rolls/R1791278/, accessed 22 March 2020.

[35] Nic Haygarth website, http://nichaygarth.com/index.php/tag/walter-malcom-black/, accessed 22 March 2020.

[36] G Weindorfer and G Francis, ‘Wild life in Tasmania’, Victorian Naturalist, vol.36, March 1920, p.158.

[37] ‘The Tramp’ (Dan Griffin), ’In the Vale of Belvoir’, Mercury, 15 February 1897, p.2.

[38] George Augustus Robinson, Friendly mission: the Tasmanian journals and papers of George Augustus Robinson, 1829-1834 (ed. Brian Plomley), Tasmanian Historical Research Association, Hobart, 1966; 22 August 1830, p.159.

[39] James Smith to James Fenton, 14 November 1890, no.450, NS234/ 2/1/15 (TAHO).

[40] ‘JS (Forth)’ (James Smith), ‘Tasmanian tigers’, Launceston Examiner, 22 November 1862, p.2.

[41] Ron Smith to Kathie Carruthers, 26 September 1911, NS234/22/1/1 (TAHO); email from Tammy Gordon, QVMAG, 2019.

[42] Bounty no.242, 30 August 1898, LSD247/1/ 2 (TAHO); ‘Court of Mines’, Launceston Examiner, 22 September 1897, p.3; 30 September 1897, p.3.

[43] Will no.14589, administered 7 March 1924, AD960/1/48, p.189 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=george&qu=francis, accessed 15 March 2020; ‘Funeral of Mr WF [sic] Knight’, Examiner, 15 April 1938, p.15.