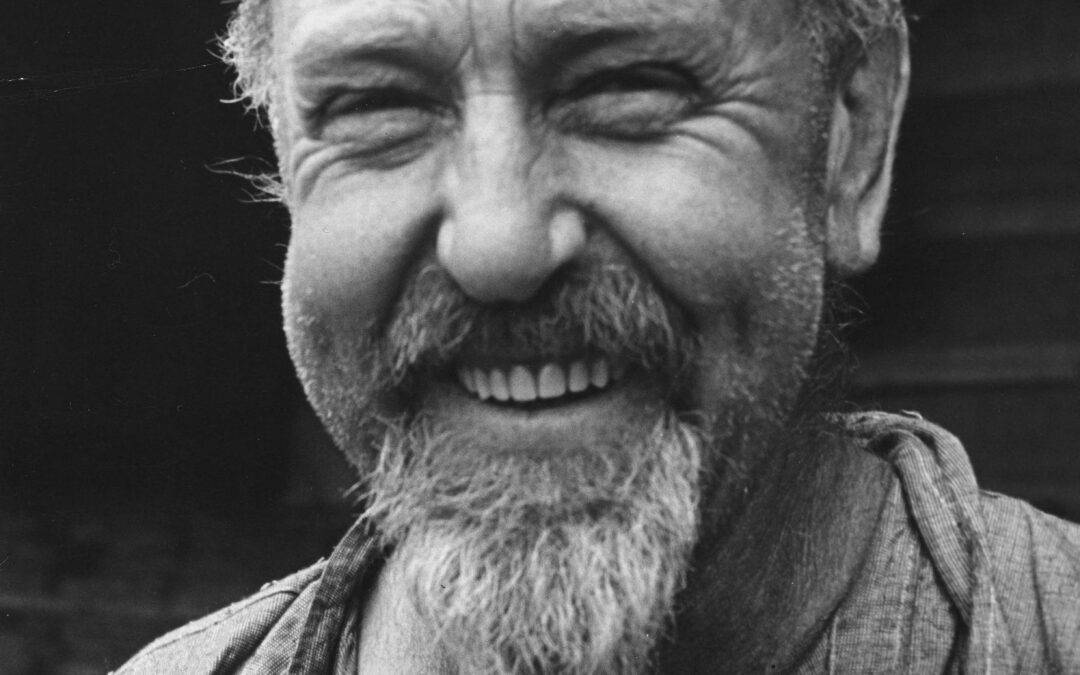

Ernie Bond (1891–1962) was more than a highland farmer: he was a facilitator, one of those figures who introduced Tasmanians to the bush. John Watt (JW) Beattie, Stephen Spurling III, Fred Smithies, Ray McClinton and Herb (HJ) King did it with photos and lantern lectures. Gustav Weindorfer, Paddy Hartnett, Bert ‘Fergy’ Fergusson and Ernie Bond played the facilitator role by establishing themselves in the highlands and inviting people to join them. They were ‘bush magicians’ whose personal charm brooked no argument.

Bond’s journey from Hobart businessman to highland guru was a strange one. It probably began with his need to address a drinking problem. It is also possible that his decisions to mine and then farm in the bush were a rejection of expectations that he would follow in his father’s footsteps as a business tycoon. There is something humbling about a failed produce merchant who sets out to ‘get his hands dirty’ by learning how to actually grow produce, just as, perhaps, he saw becoming a miner as a rebuke to his father, the razor-sharp mining investor who probably never once plunged his dish into the wash dirt.

Early life

Hobart-born, Ernie Bond was the youngest of four sons of well-to-do, self-made businessman and parliamentarian Frank Bond (c1856–1931), and Sarah Bond, née Cowburn (c1863–1934).[i] Frank Bond was enterprising in the manner of many children of ex-convicts. He became probably Tasmania’s leading mining investor, eventually buying one of the state’s major silver producers, the North Mount Farrell Mine, where he employed about 130 men.[ii] He is said to have been so astute financially that he even profited from the collapse of the Bank of Van Diemen’s Land in 1891 by buying scrip at a low price, then doubling his money when it declared a dividend.[iii]

Ernie Bond grew up at an imposing ‘gentleman’s residence’, Claremont House, Claremont; and at Gattonside, Battery Point, where the family moved c1897; while his adolescence and early adulthood were lived at Mimosa, in Elizabeth Street/New Town Road, North Hobart from 1905. Like his older brothers, George (1883–1934), Basil (1885–1932) and Percy (1888–1929), Ernie attended Buckland’s School, a boarding and day school for boys opened by former Hutchins School assistant master WH Buckland at the Barracks, Hobart.[iv] In 1905, the year that Buckland’s school amalgamated with Hutchins, Ernie achieved one pass in the Junior Public Examination which determined eligibility for the state public service.[v] He instead took a clerical job at AG Webster and Sons, produce merchants, which meant that, like his brothers, he was trained in his father’s line of business.[vi]

In October 1916 he fronted City Hall as one of 70 or 80 men between the ages of 21 and 35 with surnames beginning with A or B to enrol that day for World War One service.[vii] There was no military conscription as such, but young unmarried men were compelled to contribute to the war effort. There was also enormous public pressure to participate and, as the son of a public figure, Bond’s absence would have been noted. Perhaps he failed his medical, as he did not serve in the armed forces, and what part he subsequently took in the war effort is unknown. His brother George, who left Hobart with the original 26th Battalion in May 1915 and was awarded the Military Cross, was the only one of the Bond brothers to reach the battlefront.[viii]

Through the South Hobart Progress Association Bond became involved in local politics, supporting the political journalist Leopold Broinowski’s unsuccessful 1922 National Party candidature for the House of Representatives seat of Denison.[ix] Broinowski advocated ‘Tasmania first’, adopting the familiar theme of state rights in the federal sphere.[x] Accordingly, Norman Laird summed up his friend Ernie Bond’s political beliefs as ‘Victorian in period’.[xi]

In 1921, 29-year-old Bond took possession of a house in Ferndene Avenue, South Hobart, and married seventeen-year-old Birdie Louisa Gatehouse.[xii] Like him, she came from a well-to-do family with an enterprising convict forebear. The newlyweds had a son, Ernest Edward Bond (Ernie junior), born 18 November 1922.[xiii]

Bond at Adamsfield 1927–34

Bond would have been aware of Tasmania’s osmiridium mining industry. In the years 1918–26, before cheaper substitutes were found for it, Tasmania had a virtual world monopoly on ‘point metal’ (granular) osmiridium used to tip the nibs of fountain pens. Osmiridium won favour because of its durability. Having travelled only a short distance from its host rock, serpentine, the best metal was coarse or ‘shotty’, perfectly sized to be glued onto a nib in a New York, London or Berlin fountain pen factory. In October 1919 osmiridium reached £42 per oz., making it far more attractive to prospectors than gold.[xiv] The alluvial osmiridium of the north-western fields was worked out by the mid-1920s, but the Adams River (Adamsfield) osmiridium rush about 120 km west of Hobart in the spring of 1925 was a sensation, with several prospecting partnerships initially returning about £1000 per month.[xv] Even though many diggers only made a subsistence wage at Adamsfield, the rush was seen as something of a godsend, because Tasmania’s mining industry, like its agricultural sector, was in dire straits.

Born in comfortable circumstances, well educated, Ernie Bond was far removed from many of the osmiridium diggers, who were from poor rural farming families. At the time of the Adamsfield rush, he was a married father wielding the hammer as an independent produce merchant and auctioneer in greater Hobart and the Tasman Peninsula.[xvi] Yet for all his enterprise the business went belly up, with his own father bailing him out to the tune of £2500.[xvii] Not yet 36 years of age, Bond announced his retirement from business—which is a dignified way of withdrawing to rethink one’s options.[xviii] He had taken many steps down the path of emulating his father as public leader, businessman and politician, but all he had to show for it was public humiliation.

Perhaps his marriage was not rosy either, because in September 1927 he left wife Birdie and young son Ernie junior and went bush.[xix] ‘Mid-life crises’ were a luxury at the time, especially for a family man. It seems likely that Bond was just another of the many people—men, women and children—who trudged 42 km through mud and rain from the railway terminus at Fitzgerald to seek sustenance at Adamsfield when the osmiridium price made a temporary recovery after the market had been glutted during the initial rush. With the easily-won alluvial osmiridium now almost gone, the era of the reef miner, the hydraulic company and the investor was dawning. Bond must have invested a considerable amount of his scarce capital in buying the old ten-acre Stacey and Kingston reward claim from Turvey and Robinson in August 1928.[xx] It was worked by a horse-drawn puddling machine which separated the ‘point metal’ from ‘pug’ (clay).

Did Bond know anything about mining? Given his father’s leanings, he probably knew something about mining investment, but when it came to the nuts and bolts of it he would have been a ‘new chum’. Acting as an osmiridium buyer at Adamsfield would not have helped him much, given the low demand. The price dipped dramatically to below £9 per oz. during 1932.[xxi] ‘The diggers are desperate and starving at Adamsfield’, the old digger JS Fenton told Phil Kelly MHA in May 1934. ‘The storekeepers with there [sic] cunning can get all the metal for food alone …’ Only the government, Fenton believed, could save the miners from the colluding forces of shopkeepers and precious metal dealers who oppressed them.[xxii]

Bond’s new career on the osmiridium fields was fast evaporating, but he wasn’t destitute. When his mother died in October 1934, Bond had lost all his siblings and both his parents in the space of five years, severing some of his ties to Hobart. However, in her will Sarah Bond provided £250 for educating Ernie junior while he attended the private Hutchins School, to be expended at a maximum of £30 per year. Bond was to receive half the balance of that £250 if any remained when his son left school, plus half her trust fund.[xxiii] He owned some shares, and he received rent from his former marital home after his wife and child vacated it.[xxiv] Additional relief came Bond’s way in 1935 when he won a court battle against an alleged £2500 debt to his father’s estate, that is, the money he believed his father gave him to bail him out his business failure.[xxv]

It is clear that Bond wanted to stay in the bush. While squelching in the mud and snow as an Adamsfield digger, he would have noticed the more lucrative support services operating around him. The Quinn brothers were not miners. Hop, berry and dairy farmers, they supplemented their incomes by hunting in winter, so they knew the back country and supply routes well and were already equipped with a team of horses. Merv and Jim Quinn packed supplies to the osmiridium field and operated a store, first at the Florentine River, then at Adamsfield itself.[xxvi] However, the Quinns were less enterprising than the sly-grog merchants, Ralph Langdon and Elias Churchill, who both earned enough money on the mining field to advance to keeping legitimate, licensed premises in Hobart.[xxvii]

Perhaps Bond was also stung into action by mining field prices. One miner bought £3 worth of potatoes and onions at Fitzgerald, which cost him £28 by the time they were delivered to Adamsfield, 42 km away.[xxviii] What if he could farm closer to the osmiridium fields, undercutting all competitors? Bond’s new regime of earning a living by market gardening, plus hunting in winter, along with a little prospecting, would be a variation on the models of the bushman adopted by people like William Aylett and Paddy Hartnett and that of the Quinn brothers.[xxix] He had found a way to retain the bush lifestyle that he apparently loved. All he needed was a venue.

[i] ‘Births’, Mercury, 31 July 1891, p.1.

[ii] ‘North Mt Farrell’, Mercury, 10 April 1931, p.6; ‘Obituary’, Mercury, 16 December 1931, p.7.

[iii] Joe Cowburn; interviewed by David Bannear, 27 August 1990, in What’s the land for?: people’s experience of Tasmania’s Central Plateau Region, Central Plateau Oral History Project, Hobart, 1991, vol. 3, p.1.

[iv] ‘Scholastic’, Tasmanian News, 28 September 1893, p.2.

[v] ‘Buckland’s School’, Mercury, 1 April 1903, p.7; ‘Separate subjects list’, Mercury, 1 January 1906, p.7. For the amalgamation of schools, see Margaret Mason-Cox, Character unbound: a history of the Hutchins School, the Hutchins School, Hobart, 2013, p.22.

[vi] ‘Criminal Court’, Mercury, 28 October 1916, p.10. In 1916, at the age of 25, Bond’s position was auctioneer’s clerk (‘Police Courts’, Mercury, 7 October 1916, p.4).

[vii] ‘Proclamation Day’, Daily Post, 4 October 1916, p.5.

[viii] ‘Personal’, Mercury, 20 September 1916, p.3.

[ix] ‘Macquarie St tram’, World, 4 November 1922, p.7; ‘Denison” Mr Broinowski’s candidature’, Mercury, 13 December 1922, p.7.

[x] See Peter Boyer, ‘Broinowski, Leopold Thomas (1871–1937)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol.7, Melbourne University Press, 1979, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/broinowski-leopold-thomas-5366, accessed 30 January 2025.

[xi] Norman Laird, ‘Thylacine reports—Queen Victoria Museum—Launceston: Ernie Bond …’, NS463/1/1 (Tasmanian Archives, afterwards TA).

[xii] Conveyance 15/4889 from Robert M Ross, 21 September 1921; Bond mortgaged the property to Marion Nicolson, 16/171, on 10 February 1923 and later to Perpetual Trustees, 16/2902, 16 September 1923 (NRET); ‘Family notices’, Mercury, 30 December 1921, p.1. They married 26 October 1921. Her parents were Cecil Leonard and Elsie Harriet Gatehouse. Birdie Gatehouse was born 31 January 1904 (‘Births’, Mercury, 4 February 1904, p.1).

[xiii] ‘Family notices’, Mercury, 20 November 1922, p.1.

[xiv] Secretary of Mines (Tasmania), Annual Report, 1919, p.36. For the Tasmanian osmiridium industry generally, see Nic Haygarth, On the ossie.

[xv] ‘Register of osmiridium buyers’ returns of purchases, September 1922–October 1925’, MIN150/1/1 (TA).

[xvi] ‘New produce business’, Huon Times, 27 July 1923, p.2; conveyance 16/1651, 11 June 1923 (NRET).

[xvii] ‘Kingborough Show’, Mercury, 22 April 1924, p.2; ’Nubeena sale’, Mercury, 3 March 1926, p.10; ‘Gift or Loan?’, Mercury, 11 December 1934, p.5.

[xviii] ‘Auctioneers’ notices’, Mercury, 22 April 1927, p.10; Bond recalled the tenth anniversary of his arrival in Adamsfield in his diary entry 10 September 1937, NS1331/1/1 (TA).

[xix] The Electoral Roll for the seat of Denison, Subdivision of Hobart South for 1928, p.5, lists Birdie Louisa Marshall Bond and Ernest Bond living at 2 Ferndene Avenue, South Hobart.

[xx] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 27 August 1928, p.4; PB Nye, The osmiridium deposits of the Adamsfield district, Geological Survey Bulletin, no.39, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1929, p.42.

[xxi] Ernie Bond offered diggers £8 5 shillings per oz in November 1932, in which year the average price paid in Tasmania was £11 5 shillings 6 pence. In 1933 the average price was £8 8 shillings 4 pence. See ‘Osmiridium slight rise in price’, Mercury, 2 November 1932, p.4.

[xxii] JS Fenton to Phil Kelly MHA, 22 May 1934, MIN2/1/585–87 (TA).

[xxiii] Will of Sarah Emma Bond, no.20402, AD960/1/59 (TA), https://linctas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/all/search/results?qu=sarah&qu=emma&qu=bond, accessed 30 January 2025.

[xxiv] Electoral Roll for the seat of Denison, Subdivision of Hobart South for 1937, p.6; Ernest Bond diary, 15 January 1937, NS1331/1/1 (TA). Whether Ernie Bond was making maintenance payments to his wife Birdie Bond is unknown.

[xxv] See, for example, ‘Son’s claim upheld’, Examiner, 14 December 1934, p.9.

[xxvi] See Nic Haygarth, On the ossie, pp.131 and 143.

[xxvii] ‘Sly-grog’ in this case does not refer to the illegal distillation of spirits, but to the illegal sale of bottled alcohol from unlicensed premises. There was no licensed public house at Adamsfield.

[xxviii] Percy O Lennon, ‘The Adams River osmiridium field and the surrounding country’, Illustrated Tasmanian Mail, Christmas number, 1 December 1926, p.105.

[xxix] For Aylett and Hartnett see Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth, Mountain men: stories from the Tasmanian high country, Forty South Publishing, Hobart, 2015. Bond continued to make occasional prospecting trips to the Boyes River (see, for example, ‘Adamsfield’, Mercury, 29 December 1932, p.3) and in 1941 prospected the old Reward Claim at Adamsfield without success (Ernest Bond diary, 10 July 1941, NS1331/1/5 [TA]).