The old vehicular track up the Black Bluff Range at Smiths Plain in north-western Tasmania is scoured down to the bedrock. In places the holes are so deep and slippery that it’s difficult to clamber up; in other places you are buffeted by the scrub over-reaching from both sides. The object of the climb, the Devonport Gold Mine, has lain idle for decades, but even though the road is now impassable for vehicles you can’t help but be impressed by the enterprise of the miners in establishing it.

In making this climb on foot several years ago, I was reminded of Ron Smith’s account of the same journey more than a century earlier. Nowadays you drive to Smiths Plain and walk from there along forestry roads to the base of the bluff. Twenty-six-year-old Smith had no car. Early one morning in December 1907 he set out for Black Bluff from his home at Westwood, near Forth. A fourteen-kilogram swag was balanced on the front of his bicycle, camera (two kg) and field glasses were slung over his shoulders. Four hours after leaving home he decided to eat lunch—at 9.16 am, for all of six minutes!—near Blackwood Park at Nietta. Leaving his bicycle at a point two miles beyond Phillips’ house at South Nietta, and taking a second bite of lunch at 11.45 am, he started across the then mostly button-grass Smiths Plain.[1]

The plain took its name from it being his father’s point of entry to the high country. Prospector James ‘Philosopher’ Smith’s route over the Black Bluff Range and down to the Lea River had been his access to discoveries of gold, copper and manganese he had made in the area. Other prospectors had followed in his footsteps. One was Alf Smith, an unrelated prospector who, like others, had worked on Philosopher Smith’s farm through the winters as part of the latter’s scheme to support mineral prospecting.[2] Panning his way up Devonport Creek in 1902, Alf and his brother-in-law Reuben Richards found what they thought was a gold reef.[3] Alf worked this mine and one at Copper Creek, Lea River, building tiny huts at both sites.

No knapsacks? Alf Smith (left) and fellow miners preparing to climb the Black Bluff Range, 22 October 1909. All of them seem ill equipped for the long haul up and over the mountain. Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

The foot track of a century ago climbed a spur of Mount Jacob through eucalypt forest, affording views of the Shepherd and Murphy Tin, Tungsten and Bismuth Mine and the All Nations Tin and Tungsten Mine near Moina. Like the present-day Devonport Gold Mine vehicular track, the foot track avoided the gorge formed by a creek running eastward from Tiger Plain towards the Iris River. Today the vehicular track has spread out like a delta on both sides of the creek, suggesting that over the years people have chosen different crossing points. One day I met a bearded old man coming down the hill to the stream crossing. His flowing hair and team of dogs made me wonder if he was the ghost of Philosopher Smith returning from a prospecting expedition.

Philosopher’s son took the staked track which crossed the range to the Lea River. As it began to descend from its exposed highest point Smith diverted from it to the east, endeavouring to find the track to the Devonport Prospecting Association (DPA) Gold Mine, as it was then known. This is the opposite of today, when you take the right-hand fork, confirming that the vehicular track did not follow the line of the earlier walking track up the hill. The walking track went further to the west, closer to the edge of Golden Cliff Gorge, the great north-south rift through the Black Bluff Range caused by a fault line.

At last Smith found the fallen stakes denoting the DPA track. He reached Alf Smith’s hut at 4.25 pm, after a journey of more than nine hours from Forth. The hut, Smith wrote, was built of red (pencil) pine, there being a small stand of it nearby. It had

‘a fireplace at the east end, and a verandah on the north side, under which the door opened. Two bunks (single), one above the other, took up the west end and a double bunk half the north side … A window, one large sash, was in the south side’.[4]

The hut was well furnished, with table, stools and even cooking and eating utensils. Next day Smith visited the trig station on Black Bluff, travelling mostly by compass through the mist, and photographed the DPA adit and the blacksmith’s shop near it.[5]

It was a poor gold mine. Early assays approached a very respectable ounce per ton, but this was due to the sampling of surface enrichment that could not be expected to continue at depth. Examining both the irregular quartz vein cut in the adit and the gossan accessed in trenches, in 1913 Government Geologist William Harper (WH) Twelvetrees predicted only ‘negligible quantities of gold’ at depth, with the ore changing to iron sulphide.[6] Subsequent geological reports and returns confirmed this, but the allure of gold kept men coming.[7]

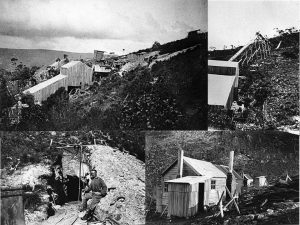

Alf Smith’s hut at the Devonport Prospecting Association (DPA) Mine, 1907.

Ron Smith photo courtesy of the late Charles Smith.

Depreciation of the British pound in 1931 gave the gold price a boost. In a repeat of the 1890s depression, diggers retried old gold shows, hoping to plunder a supposed reef that had failed to yield its treasure last time. Hunting also drove men into the bush, with 1934 being a record season for ringtails. Cliff Beswick and Reg Ling were reworking Black’s Lea River Gold Mine when Bernard ‘Barney’ Fry walked off a nearby cliff while out possuming by acetylene light.[8] Cashman’s Gold Mining Syndicate sank new shafts and extended one of the adits in search of the Lea River lode in 1940.[9]

(Clockwise from top left) Probably 1950s photos of the gravity-fed mill; the trolley way from the adit to the mill; the entrance to the adit; and the huts, Devonport Gold Mine. Colin Dennison Collection, University of Tasmania Archives.

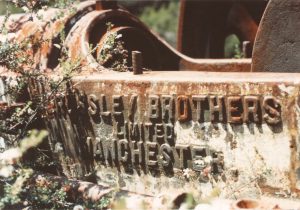

The final abandonment of the mine left infrastructure to crumble high on the exposed spine of Black Bluff. Historian Dr Peter Bell’s examination of the overgrown, plundered site in 1995 revealed a technological morass, including a 1923 Crossley oil engine that was set up to power a treatment plant on the opposite side of Devonport Creek, a Forwood Down grinding pan, a 1920s–30s Lister oil engine, a steam winding engine and a late-nineteenth-century Cameron steam pump. The purpose of some of the gear was by then unfathomable.[12]

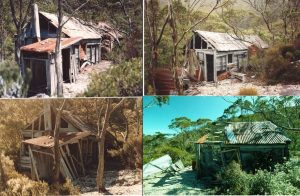

Devonport Mine hut from the rear, looking towards Stormont and the Lea River valley. Nic Haygarth photo.

The remains of what was probably the blacksmith’s shop; and the adventures of Chunder Loo, Devonport Gold Mine, 1995. Nic Haygarth photos.

The two-room hut still stood, although the broken windows were covered up and the exterior boards appear to have been torn off and used for firewood, exposing the wall cavities to the elements. There was no recovery from here without urgent attention. Inside the hut you could read the wallpaper—pages of Sydney magazine the Bulletin from 1915! (One of the pages featured ‘Chunder takes a trip home’, satirical verses by Ernest O’Ferrall, whose Sri Lankan character Chunder Loo originally appeared in newspaper advertisements for Cobra boot polish. O’Ferrall’s Adventures of Chunder Loo, illustrated by Lionel Lindsay, was later issued as a book, with verses appearing in the Bulletin.)[13] This aged wallpaper suggested that part of the hut, at least, dated from the first operation of the mine, possibly even incorporating elements of Alf Smith’s pencil pine hut.

The vehicular track enabled the Crossley to be removed from the mine, reducing the site’s integrity but allowing restoration of the now rare engine at Pearn’s Steam World, Westbury. Since the exterior walls were removed, the two-room hut has declined rapidly, such that within a few years there will be no standing walls at the Devonport Mine. Rarely was gold fever more virulent than here, defying geological argument for most of a century.

[1] Ron Smith diary, 13 December 1907, NS234/16/1/4 (TAHO).

[2] Nic Haygarth, Baron Bischoff: Philosopher Smith and the birth of Tasmanian mining, the author, Perth, Tas, 2004, p.136.

[3] ‘A Barren Bluff find’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 19 February 1902, p.3.

[4] Ron Smith diary, 13 December 1907.

[5] Ron Smith diary, 14 December 1907.

[6] ‘Middlesex district’, North West Post, 5 March 1914, p.4.

[7] See, for example, QJ Henderson, ‘Departmental report on the Devonport Mine, Black Bluff’, Unpublished reports, 1939, pp.61–64.

[8] ‘In darkness: stumbled over cliff: hunter’s death’, Examiner, 5 June 1934, p.7.

[9] ‘Gold at Black Bluff’, Examiner, 13 March 1940, p.4.

[10] ‘Gold at Black Bluff’, Advocate, 9 March 1942, p.4.

[11] Peter Bell, Devonport Mine near Black Bluff: report to Tasmania Development and Resources, Archaeological Survey Report 1995/03, Historical Research Pty Ltd, Adelaide, 1995, p.2.

[12] Peter Bell, Devonport Mine near Black Bluff, pp.1–4, 17–18, 24–26.

[13] Douglas Stewart Fine Books website, https://douglasstewart.com.au/product/adventures-chunder-loo/, accessed 14 December 2018.