In the centre of Tasmania is an entertainment zone where the rules of decency are blurred. He-men brandishing ski poles, their bare nipples lasering the path to the Narcissus jetty, bleeding kids wondering if leeches are protected by UNESCO, beautiful, unwashed young couples smelling like a long-drop and swarms of flies experiencing the disappointment of tofu all help pickle the romance of the Overland Track between Dove Lake and Lake St Clair.

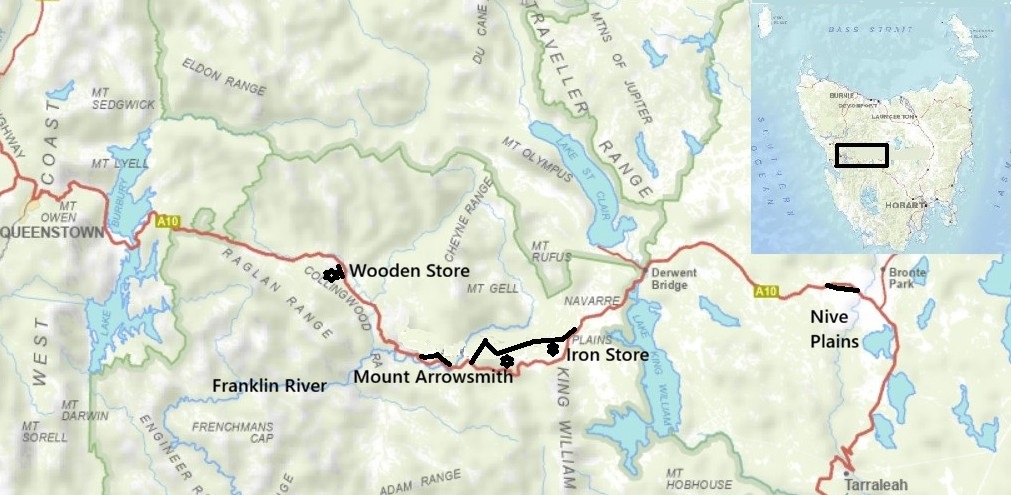

What about the original Overland Track? How did that compare as a mountainous hikeathon? Ye olde Trip Advisor is silent on that one. Snaking a path between the Nive River district and Mount Lyell, this Overland Track was Hobart’s nineteenth-century conduit to mining riches. The Linda Track, as it was otherwise known, bore a hint of James Calder’s 1840s trackwork but its heart was late-Victorian. Its comforts were too. No boardwalks, no signage, no tent platforms, no rangers, no chai-latte-tendering, guided private expeditionary services. Only a few bridges over major streams but plenty of opportunities to die of exposure. The history of the Linda Track is spiced with the same arguments about public safety as that of the present Overland Track—but at least it had Tom Moore as a guardian.

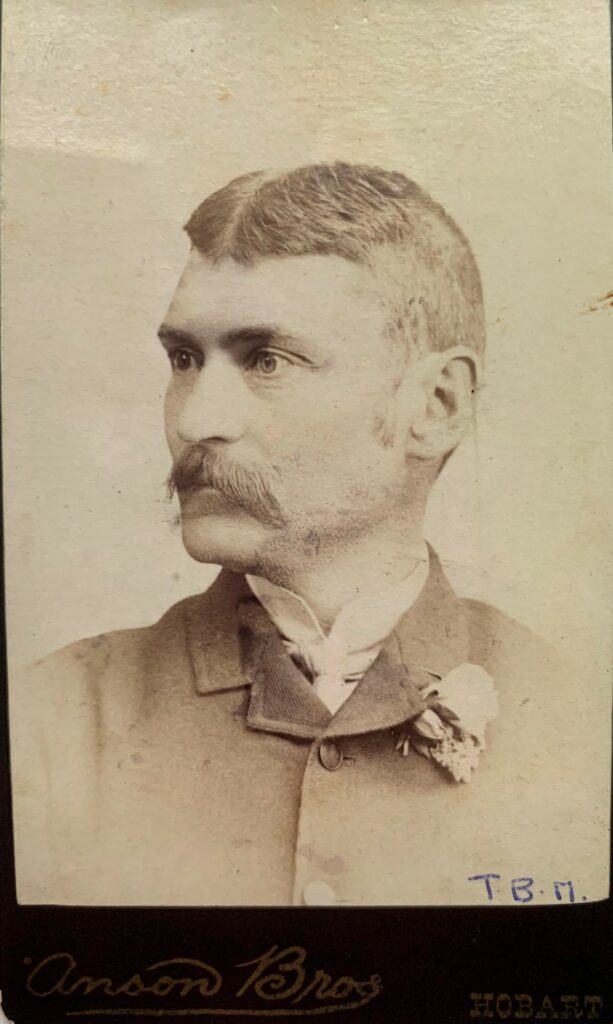

Tom Moore and the Mount Lyell Iron Blow

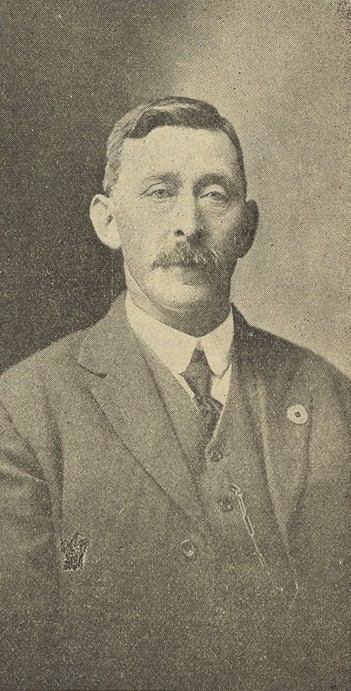

Anyone who has been a prisoner of their own tent will wonder at the curiosity, the ambition and the dedication of Thomas Bather Moore (1850–1919, aka Tom Moore or TB Moore). Each night in the bush, after retiring rain-sodden from the mud and a feed of echidna or wallaby, by candlelight in his tent Moore kept his immaculate diary, sometimes adding lines of philosophical verse, botanical notes or observations of comets and earth tremors. Moore’s solitary exploration work, endurance and scientific interests made him a legendary figure on Tasmania’s West Coast.

His chance to be known as a successful mineral prospector went begging—and this is really where the story of the Linda Track begins. In February 1883 Moore and a party of three including his brother Jim (JLA) Moore searched for an access route from Lake St Clair through to the West Coast. Near Mount Arrowsmith they established a supply depot. During the trip Moore named many features which are seen along the present-day Lyell Highway.[1] Entering the Linda Valley, Moore’s party climbed into the divide between Mounts Owen and Lyell, and while traversing what is now Philosophers Ridge discovered copper and iron pyrites. They also noticed the dark-coloured formation of boulders later known as the Iron Blow. According to Moore, another prospector and track-cutter, Tom Currie, found gold at or near the Iron Blow before being forced to withdraw from the field by illness.[2]

Moore’s party was in no hurry to examine the Iron Blow. The appearance on the scene of ‘new chum’ prospectors, the brothers William and Michael McDonough, plus Steve Karlson, did not worry the Moores either, since they believed they only wanted to prospect the creeks for alluvial gold.

When Moore next visited the Iron Blow site, he was surprised to discover that the McDonoughs and Karlson had pegged a 50-acre prospecting area around the Iron Blow. Moore later conceded that underestimating the ‘new chums’ had cost him the chance to peg one of Tasmania’s greatest mineral treasures.[3] However, had Moore pegged the Iron Blow, it is possible that he would have fared no better than the prospectors who did. Their shares were surrendered for want of money, service providers and sharp investors being the beneficiaries of their plight.

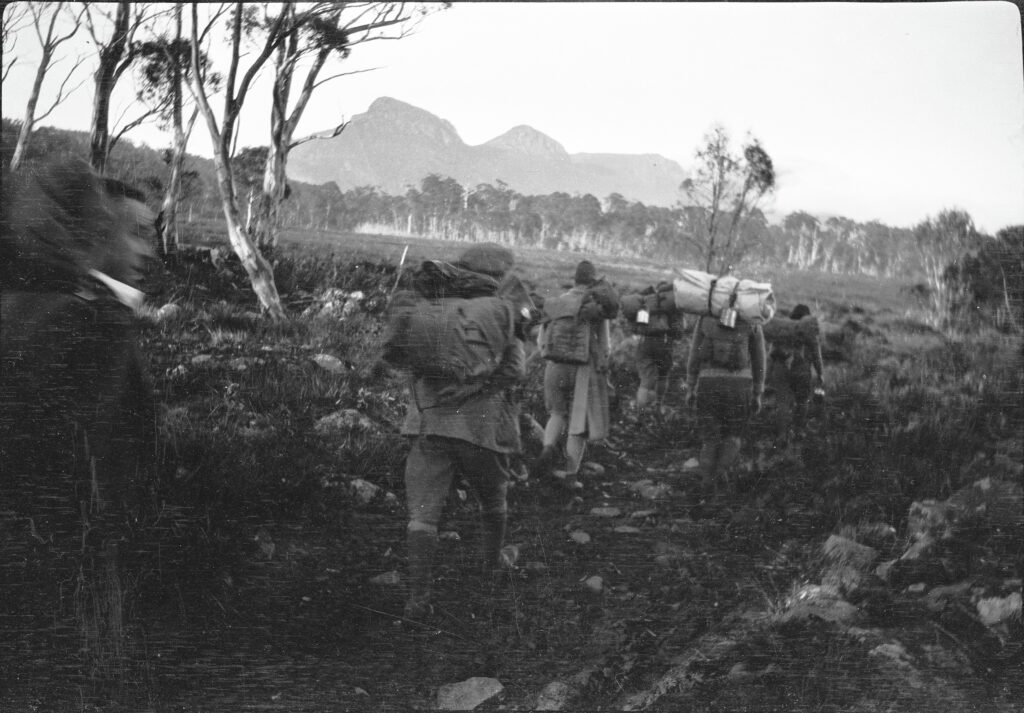

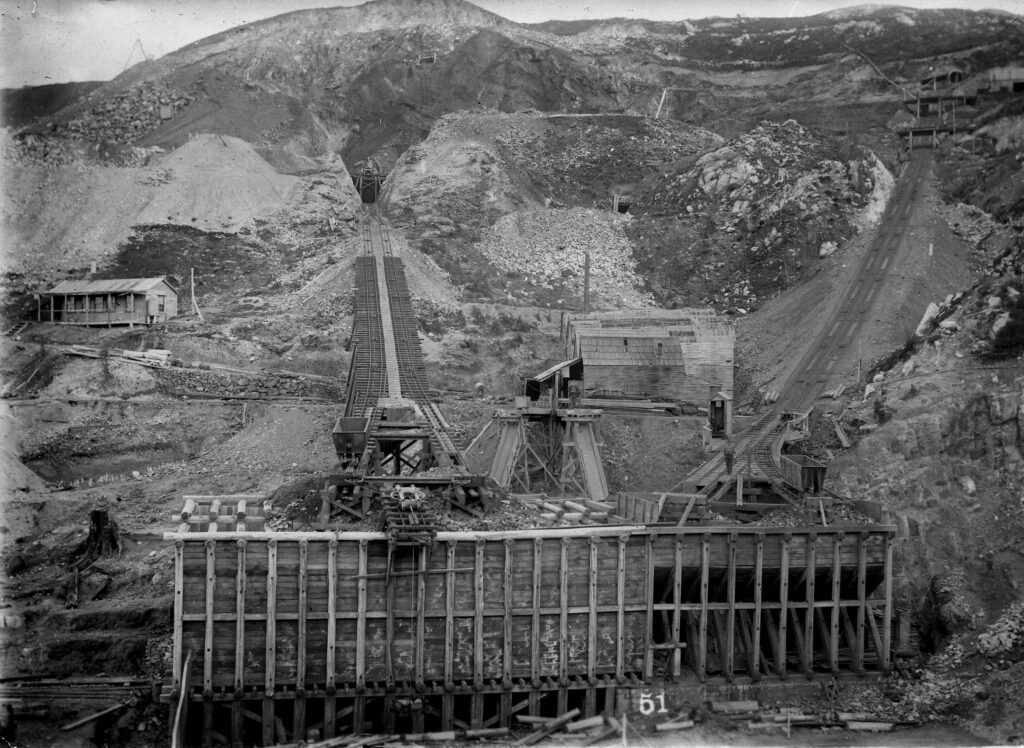

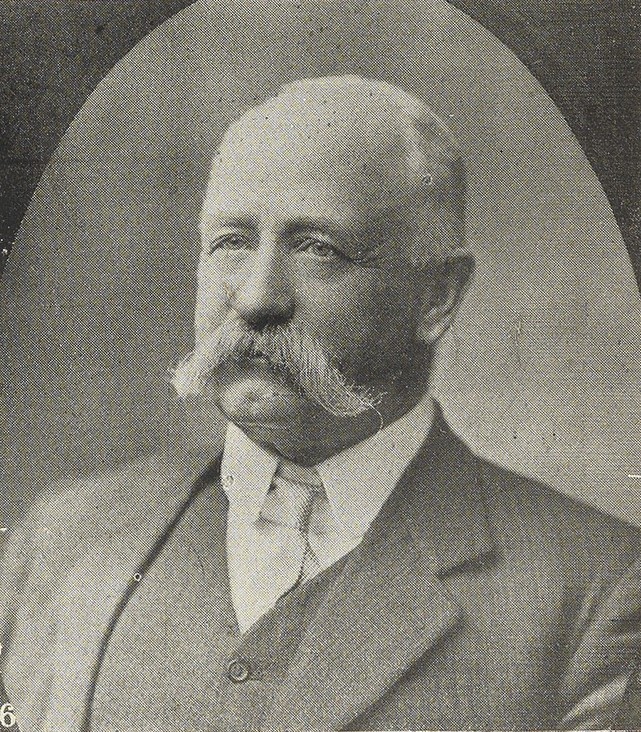

Jack Thwaites photo, NS3195/2/1475 (TA)

Jack Thwaites photo, NS3195/1/313 (TA)

Cutting the Linda Track

Moore’s only consolation from his Iron Blow blunder was obtaining track-cutting work that served the discovery. The goldfield attracted a lot of attention in Hobart. In November 1885 he applied for the position of superintending overseer in the construction of the proposed track from the Marlborough property on the Nive Plains via the Collingwood Valley to the King River goldfield. Engineer of Roads William Duffy recommended Moore’s appointment because his knowledge of the country would be valuable in determining the route and securing the best line.[4] Moore accepted a salary of £4 per week, his duty being to mark a track in advance of the work gangs.[5] He showed the value of his experience immediately upon arrival at the Clarence River when he suggested a better way to supply the men and larger work gangs. He recommended setting up a store and employing a storekeeper. Pack-horses which conveyed supplies, Moore contended, could also be used in the haulage of logs and timber.[6]

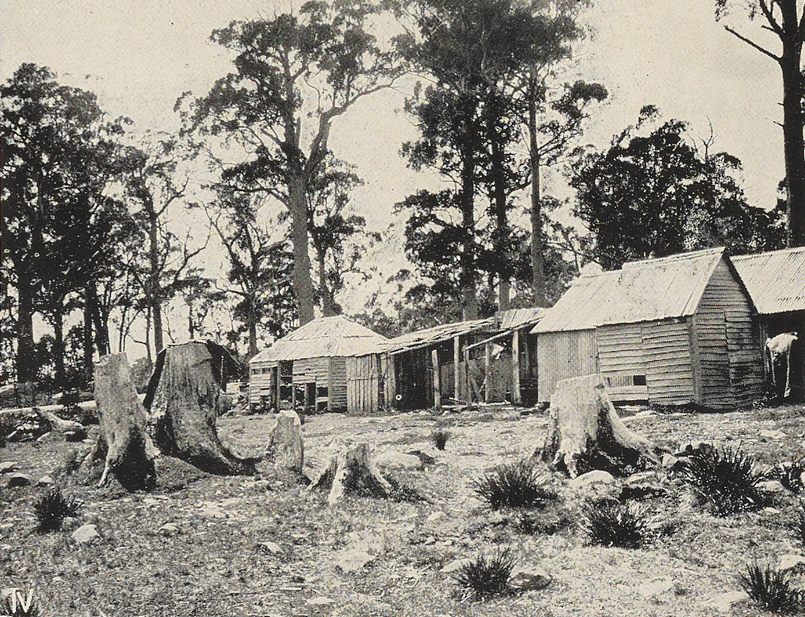

Building the Iron Store

In his track work Moore chose to follow the general line of his 1883 route to Mount Lyell, settling on a route over Mount Arrowsmith.[7] He decided to erect the so-called Iron Store at King William Creek, on the site of his 1883 supply depot, the materials being packed in from Hobart. George Bray was appointed storekeeper. No additional hut was built simply for shelter at this time, although before the season closed Moore’s fellow overseer George Walch erected a slab stable to accommodate four horses.[8] Moore resented sharing command with Walch, whose management style frustrated him. He sought to undercut the other man by suggesting efficiencies and better methods of bridge building.[9]

Meanwhile, the track builders worked nine hours per day instead of the prescribed eight through the autumn, with the understanding that they were paid for days when the weather made it impossible to work. Moore proved a difficult man to control from head office. When ordered to stop work in April 1886, he refused, claiming that there was at least a further month of good weather ahead. Engineer of Roads William Duffy complained that ‘It will be impossible to work with a gentleman who refuses to obey such simple and necessary routine orders’.[10]

site of the first Wooden Store, in the foreground at left. Shane Pinner photo.

Building the Wooden Store

Duffy got over it. The Lands Department needed Moore’s knowledge and drive. Moore requested the construction of another stores depot and shelter hut in the Collingwood Valley which would ‘eventually be useful as a halfway shelter hut’.[11] This hut was among the future needs he listed in his diary:

Stable at the Collingwood River 24 long 9 ft wide

6 ft being 12 front high & four stalls & chaff house 4 ft wide

(Palings 280 6 ft 200 5 ft) (4.6 wide)’

Huts required

From store depot [Iron Store]

Timber can be obtained without much difficulty.

West bank of Franklin R. 7 or 8 miles

West bank of Collingwood R 15 to 16 —

The Bubbs Victoria Pass 25 or 26 —

Huts to be built of six feet palings

18 feet long 10 feet wide 6 feet high

rafters 7 feet long, partition for sleeping 8 wide

with 4 feet chimney (store room 10 x 10 wide)

with door lock & key 2 ft sq window in gable with hinges & fastenings

Packings required 6 ft 525[12]

While Moore’s plans for huts at the Franklin River and Bubbs Hill were shelved, the so-called Wooden Store and stable were built on the edge of the Linda Track at Redan Hill, overlooking the Collingwood River. These buildings lasted only a dozen years, gradually being destroyed by travellers, with the bunks pulled out, the door ripped off its hinges, the window broken and the timber chimney attacked with an axe.[13]

Gold at Mount Lyell

In the winter of 1886 reports of fabulous gold assays circulated from the Mount Lyell Iron Blow. Inspector of Mines Gustav Thureau compared the Iron Blow to the famous gold deposits of Mount Morgan in Queensland, predicting a bonanza of ‘practically inexhaustible’ gold at Mount Lyell.[14]

The Iron Store showed its value as a shelter when excited investors despatched mining ‘experts’ to inspect Mount Lyell. In February 1887 Iron Storekeeper Bray took pity on one of them, Theophilus Jones, the itinerant, poverty-stricken journalist who was wending his way back to Hobart after being abandoned by the newspaper that sent him out. Jones reported gratefully that

Mr Bray, with that fine feeling, often displayed by those used to fatigue towards another on the march, insisted on my being seated to gain all the rest possible, whilst he went to the stream for a billy of water to make the ever refreshing tea, and when the infusion was ready helped us bountifully to his stores of tinned meat, etc.[15]

The Mount Lyell Gold Mining Company was registered in Launceston in 1888, echoing the momentous establishment of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Company there fifteen years earlier.[16] Unfortunately, Mount Lyell also had a much more complex ore body than Mount Bischoff, and was more isolated requiring more capital investment than the Launceston company could raise.

The trail runner for the telegraph line

The present Overland Track measures 65 km from Dove Lake to Narcissus, with four intervening huts. The original Overland Track was 98 km from Nive Plains to Mount Lyell with initially just two huts. 1890s telegraph lineman Alfred Taylor would challenge modern ultra athletes skipping from Cradle to St Clair in a day. Broken culverts and fallen trees forbade horse travel along the Linda Track in the early years. Thus Taylor often hotfooted 138 km in three days from the Clarence River to Strahan. The ravenous tiger cats at the Iron Store may have prompted Taylor to sprint 58 km on the first day to avoid it by reaching the Wooden Store. A swig from the brandy flask would help him sleep through the cold (in winter) and the mosquitoes (in summer). Next stop was the Queen River Hotel, 45 km further on, where a jug of beer awaited him. Strahan, the end of the journey, was another 35 km beyond that. If a steamer was in port, Taylor would take the 6.5-day voyage to Hobart, otherwise retrace his steps to his home at Dee River.

The telegraph line from the Iron Store to Strahan, connecting Hobart to the western seaboard, was the work of brothers John, James and David Pearce in 1891–92. Taylor supervised their contract work and then continued as lineman. He described a daily menu of bully beef, bacon, wombat and honey stolen from hives in the myrtle forest; and a daily routine of being soaked to the skin and camped knee-deep in mud among swarming tiger cats. Leeches didn’t seem to bother him.[17]

Taylor the human snow plough

The annual Cradle Mountain Run now pushes marathoners the full 80 km from Cradle to the southern end of Lake St Clair. How would they have fared on the Linda Track without duckboards, thermals and satellite phones in the great snows of 1894 and 1900? Taylor turned yeti in these conditions. On Mount Arrowsmith he ploughed through snow drifts up to 5 m deep. Sometimes 60 cm or more of snow were frozen hard on the top of each tree used as a telegraph pole. Bashing the base of the tree to unfreeze it, he would sometimes receive the bulk of the snow down the front of his shirt, giving him a counterweight to the icicles hanging from his nose and moustache.[18]

Taylor got no help from fellow travellers. By 1896 the only way to keep the rain out of the Wooden Store was to stuff clothes in the open window hole.[19] Two years later ‘the old barn with chimney and door down and windows out’ was replaced by a new iron ‘Wooden’ Store, stable and cattle yard built much closer to the Collingwood River.[20] However, the location proved just as boggy as the old one, with mud several feet thick being reported after the ground was churned up by horse traffic.[21] The mosquitoes there were reportedly ‘intolerable’.[22]

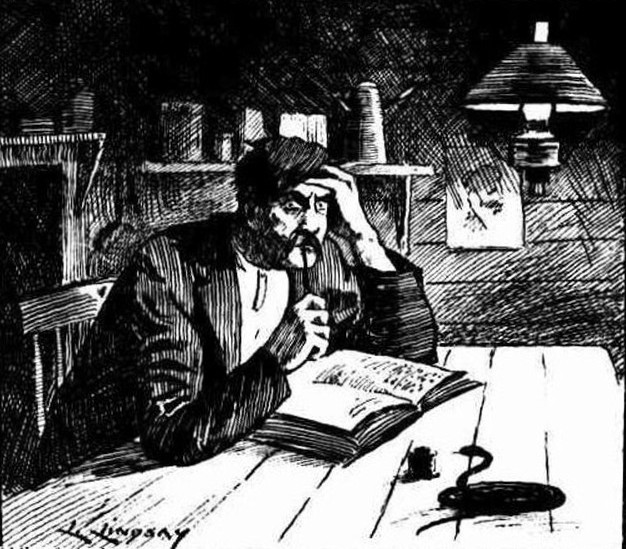

From Free Lance, 14 May 1896, p.14.

Sydney Page’s coach service

In 1896 a writer calling himself Arthur Conway penned a screed about a storekeeper losing his sanity ‘in the house of the ungodly’, a tin hut on the Linda Track known as the Iron Store. In the solitude, with only the tigers and devils for company, Hugh Garland succumbed to the snake.[23]

The serpent might have been trampled by the hooves of the coach service in the following year.[24] The Mount Lyell Copper Mine was then the subject of Australia’s last national mining boom of the nineteenth century.[25] Foot traffic on the improved track increased to the extent that Sydney Page, son of the late stage-coach entrepreneur Samuel Page, tried a coach and horse service between the rail head at Macquarie Plains near Glenora and Gormanston, the miners’ town for the Iron Blow. The stage-coach section had stopovers at the Jenkins residence, Dee River, and the Lake St Clair Accommodation House, before travellers reached the coach terminus of the Iron Store. On day four they set off on horseback across Mount Arrowsmith, overnighting at the Wooden Store beyond the Collingwood River.[26]

The service didn’t last long, because while Page’s nags were kicking over the gibbers northern interests were waging a ‘railway war’ to send a line westward. In 1899 the Emu Bay Railway Company laid rails into Zeehan, completing a connection with Mount Lyell. The Linda Track remained Hobart’s overland route to the west until in the late 1920s—about the time Ron Smith conceived the idea of the present Overland Track—the Lyell Highway obliterated much of it. Further tales of the original Overland Track will follow.

[1] These included Artist Hill, in keeping with nearby Painters Plain, and Junction Peak, at the junction of the Franklin and Collingwood Rivers. In the Collingwood River Valley Moore named several features (Redan Hill, Raglan Range, Scarlett Hill, plus the Inkerman, Balaclava and Cardigan Rivers) to complement Charles Gould’s Crimean War reference of the Alma River. Further west he christened Nelson River after his godson Nelson Brent, the Princess River in keeping with the King and Queen Rivers and Thureau Hills after Inspector of Mines Gustav Thureau (TB Moore diary, 1974–87 compilation, ZM5618 [TMAG]).

[2] TB Moore diary, 1974–87 compilation, ZM5618 (TMAG); TB Moore, ‘In the early days of Mount Lyell: the first discovery of gold on the Mount’, Mount Lyell Standard and Strahan Gazette, 5 December 1896, p.4; TB Moore, ‘Discovery of Mount Lyell Mine’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 12 May 1919, p.1.

[3] TB Moore, ‘Discovery of Mount Lyell Mine’.

[4] William Duffy, notes written on the back of Moore’s application, PWD18/1/966 (TA).

[5] TB Moore to the Minister of Lands, 3 December 1885, PWD18/1/966 (TA).

[6] TB Moore to the Minister of Lands, 21 January 1886, PWD18/1/966 (TA).

[7] TB Moore diary, 1874–87 compilation, ZM5618 (TMAG).

[8] Overseer George Walch to the Director of Public Works, 1 May 1886, PWD18/1/966 (TA).

[9] TB Moore diary entry, 15 March 1886, ZM5620 (TMAG); Moore to Minister of Lands, 26 March 1886.

[10] William Duffy, Engineer of Roads, memo for Overseer George Walch, 28 April 1886; William Duffy, Engineer of Roads, memo dated 19 May 1886, PWD18/1/966 (TA).

[11] TB Moore to William Duffy, Engineer of Roads, from Iron Store, 3 March 1886, PWD18/1/966 (TA).

[12] TB Moore diary, 1886, ZM5620 (TMAG).

[13] ‘On the Overland Track: Gormanston to Arrowsmith’, Mount Lyell Standard and the Strahan Gazette, 4 September 1900, p.2.

[14] Gustav Thureau, The Linda Goldfield: its auriferous and other mineral deposits, Department of Mines, Launceston, 1886, pp.1–3.

[15] Theophilus Jones, ‘The west coast goldfields’, Tasmania’, Daily Telegraph, 10 February 1887, p.3.

[16] ‘Mount Lyell Gold Mining Company’, Daily Telegraph, 21 January 1888, p.3.

[17] A Taylor, ‘Ten years on the Ouse–Zeehan telegraph line’, Tasmanian Postal-Telegraphic Journal, vol.1, no.1, November 1900, p.7.

[18] A Taylor, ‘Ten years on the Ouse–Zeehan telegraph line’, p.8.

[19] M Wilkes Simmons, ‘Westward ho!: the experiences of a Hobart tourist party’, Mercury, 24 November 1896, p.2.

[20] ‘The west coast’, Mercury, 26 August 1898, p.3; A Taylor, ‘Ten years on the Ouse–Zeehan telegraph line’, p.8.

[21] ‘On the Overland Track’, Mount Lyell Standard and Strahan Gazette, 4 September 1900, p.2.

[22] ‘The Wombat’, ‘Tramping across Tasmania’, Weekly Courier, 4 June 1908, p.35.

[23] A Conway, ‘The guardian of a bye-way’, Free Lance, 14 May 1896, pp.14–16.

[24] ‘The way to the west’, Daily Telegraph, 23 February 1897, p.2; ‘Rural jottings’, Launceston Examiner, 16 March 1897, p.7.

[25] Geoffrey Blainey, The peaks of Lyell, Melbourne University Press, 5th edn, 1993 (originally published 1954), pp.58 and 79.

[26] ‘The way to the west’, Daily Telegraph, 23 February 1897, p.2; ‘Rural jottings’, Launceston Examiner, 16 March 1897, p.7.