The man with the possum-skin bag on his back studied the rocks as he sloshed his way down the river with Bravo, his collie-spaniel cross. James ‘Philosopher’ Smith sought the motherlode of the Arthur River gold. Ahead of him, the low summer stream rippled as it received a tributary from the east. Smith’s partly speculative Henry Hellyer map suggested that this was the Waratah River. In its dark mouth he searched for wash—sand and detritus carried down by the current—and promising rock formations. At a sandbar he swirled something black in his dish which in the half-light resembled tin. He had seen tin oxide almost two decades earlier at the Victorian gold rushes, but the tiny quantity in his dish now caused him no excitement. He returned to the Arthur to resume his search for gold.

It was only two days later, when the sun’s rays poked through the myrtle forest, that the opportunity arose to examine the sample under the lens. What struck Smith about it was that many particles were angular. The sample was little waterworn, which meant he had found it close to the matrix.

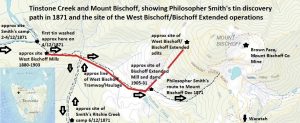

Smith rushed back to the ‘Waratah’, which was actually today’s Tinstone Creek. For a further two days he panned and picked at the course of the stream, but it wasn’t until he ventured above its Ritchie Creek confluence that his pick opened the bed of porphyry he sought. The adrenalin must have pumped as he climbed the stream. Within a few minutes he obtained a quarter of a kilogram of tin ore. He picked crystals out of crevices in the creek bed, and at the source of one of its tributaries, where Mount Bischoff Co tailings were later piled, Smith washed more than a kilogram of tin to the dish. He had found the motherlode.[1]

A ‘mountain of tin’, Mount Bischoff, stood above him. Over 74 years the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Company would produce 56,000 tonnes of tin metal and pay dividends of more than £2.5 million on paid-up capital of only £29,600, one of the great success stories of Australian mining.

As usual, the company with the first choice of ground and best access to capital dominated the mining field. That wasn’t the West Bischoff Tin Mining Company which, ironically, worked in the valley where Smith made his discovery. Take a walk in Philosopher’s footsteps and you can see the scars of its struggle.

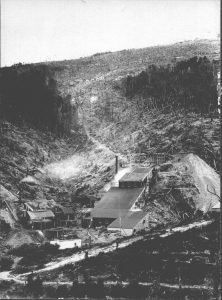

The West Bischoff’s early mill site is not far from Philosopher’s discovery point near the junction of Tinstone Creek and the Arthur. That’s about as close as the company got to success. Here Cornish tin dressers WH Welsey and William White worked with a 15-head stamper battery driven by a 28-foot-diameter waterwheel. The plant was served by races from Ritchie Creek and the Arthur River, an inadequate water supply which probably reduced the company’s viability.[2] Beginning with a paid-up capital of £20,000, between 1878 and 1892 the West Bischoff Co made 26 calls on shares—and paid no dividends whatsoever.[3]

race. Nic Haygarth photo.

A 2.5km-long wooden, horse-drawn tramway and haulage connecting the plant to the mine in the western flank of Mount Bischoff included a 30-metre-long bridge over Ritchie Creek. [4] Thanks to Winston Nickols’ dogged research, track cutting and marking, much of the old tramline can now be retraced along the edge of the highly degraded Tinstone Creek. The impressive tramway cuttings and the horrible, spindly regrowth resulting from clearing the old forest give some idea of the original company’s enterprise. The yellow glop in the creek is fed by acid mine drainage (that is, low level sulphuric acid) escaping from the West Bischoff/Bischoff Extended adits.

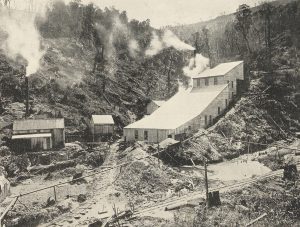

By March 1892 the West Bischoff Co had driven its no.3 tunnel more than 400 metres, but the cost of all the infrastructure left it unable to afford a calciner which could have purified its ore by roasting out the arsenic.[5] The company was wound up, being replaced by another inadequately funded company, the New West Bischoff. The infrastructure on the property was by now so run down that it was cheaper to crush at the adjoining Stanhope Tin Mining Company battery than use its own, so the company employed Stanhope Co manager Richard Bailey to run the two mines concurrently.[6] While the New West Bischoff facilitated this change by building another tramway, in January 1893 its own plant was destroyed by bushfire.[7]

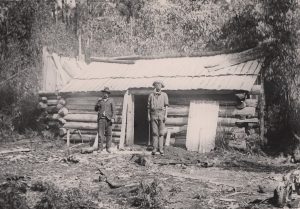

The signs of this fire remain today at the multi-levelled site of the old mill, where the stamper rods, blacksmith’s shop, boiler stack and water wheel pit are still evident. The New West Bischoff lurched towards defeat. No Australian buyer wanted its unroasted arsenical tin ore, forcing it to ship it to England for treatment and sale.[8] The bank foreclosed on the company, finally selling the property to Wynyard investor Robert Quiggin in 1895.[9] After seventeen years of work at this site, the first dividend remained elusive.

The route from Waratah down Tinstone Creek to the Arthur River and over the Magnet Range was cut as a track in 1879, and when the mining settlement of Magnet was established in the 1890s it became an 8km pedestrian conduit between Waratah and its satellite mining town. Come night or day people padded between the centres, attending dances, courting darlings, cutting firewood and even moving stock. Today you rarely glimpse the ‘glorious’ walk of yesteryear, that ‘never-ending avenue of most beautiful greenery which arches overhead so closely at times as to form a veritable living tunnel’.[10]

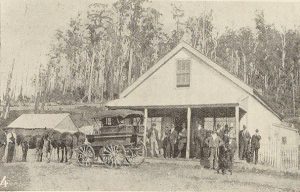

No record survives of anyone hitching a ride up the hill on the West Bischoff tram, but those passing the old burnt-out mill site in 1901 would have dodged horse teams, haulage contractors and carpenters. A third company, the Mount Bischoff West Tin Mining Company, registered in Victoria, was building a new mill. It had paid-up capital of only £16,000, but a higher tin price in its favour.[11] Another crushing device, a Krupp ball mill, replaced the original battery and two concentrating tables were installed to separate the ore. The machinery was driven by a water-driven 98-horsepower turbine.[12] Drop in to see the concentrating tables and the amalgamating pan that possibly replaced the ball mill. The latter must have proven too hard to salvage when in 1903 the plant was abandoned and the property left in limbo again.

Nic Haygarth photos.

So far we have tarried in the bottom end of the Tinstone Creek valley. Now we cross Ritchie Creek, up which Philosopher camped after getting side-tracked trying to trace the tin. Above this confluence he rediscovered the black waterworn particles of the cassiterite or tin oxide that later made the Mount Bischoff Co famous. By the late 1890s this company had bought out most of its early rivals, but it saw no advantage in buying the West Bischoff property. Instead, in 1905 company number four, the West Bischoff Extended Tin Mining Company (later simply the Bischoff Extended), took over the leases and erected a new mill much higher up Tinstone Creek below its mine. When the scrub was lower than present you could still see the brick chimney and roaster shafts of its 1910 calciner, the first on the Bischoff field.[13]

From here on Mount Bischoff was a two-horse tin field. The better capitalised Mount Bischoff Co threw its weight around, alleging that the Bischoff Extended had encroached onto its lease. The expensive High Court law suit which resulted hampered the struggling company’s progress.[14] So did reduced production when World War One closed the European metal market.[15] The first dividend, 39 years in the making, was declared in 1917, but although several more followed up until 1920, the company soon returned to making calls on shares. Further technical advances, including electrification of the plant in 1925, were made in the face of rising costs and falling metal prices.[16] Mostly sporadic operation continued until the mine was abandoned in 1931.[17] A six-bullock team hauled a large boiler up the hill to Waratah, but much of the plant remains on site rusting ever deeper in the regrowth.[18] Welcome to the Tarkine industrial wilderness.

Your walk in Philosopher’s footsteps has now reached the base of the hill below Mount Bischoff. It’s a hard slog to the top, but imagine how much worse it was for the man on a daily ration of 100g of bread and a pint of tea.[19] That dish full of ‘black gold’ he won at the head of Tinstone Creek was the only tonic Smith needed. He had no food but he had a fortune. For the Mount Bischoff Co’s smaller rivals, destined to collect ‘the crumbs from the rich man’s table’, there was no pay-lode and no payday, just bread-and-butter toil for the working man and a poisonous legacy for the upper Arthur River.

[1] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/1/14/3 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, afterwards TAHO).

[2] HK Wellington; in DI Groves, EL Martin, H Murchie and HK Wellington, A century of tin mining at Mount Bischoff, 1871–1971, Geological Survey Bulletin, no.54, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1972, pp.61 and 64.

[3] Journal of the West Bischoff Tin Mining Company, NS1012/1/51 (TAHO).

[4] James FitzHenry, ‘Mount Bischoff’, Tasmanian Mail, 9 July 1881, p.21.

[5] Pretyman to FA Blackman, 23 March 1892, NS1012/1/45 (TAHO).

[6] Pretyman to Robert Mill, 25 August 1892, NS1012/1/45 (TAHO).

[7] For the tramway, see Pretyman to Richard Bailey, 7 December 1892, 14 December 1892 and 18 January 1893. For the fire, see Pretyman to Richard Bailey, 17 January 1893, NS1012/1/45 (TAHO).

[8] Pretyman to Richard Bailey, 29 September 1892; Pretyman to Claperton, 24 January 1894; NS1012/1/45 (TAHO).

[9] Pretyman to Richard Bailey, 9 August 1895, NS1012/1/45 (TAHO).

[10] ‘WGT’, ‘Further rambles with the Scouts’, Advocate, 26 January 1924, p.12.

[11] ‘Mount Bischoff West’, Examiner, 14 March 1901, p.2.

[12] ‘West Bischoff tin mine’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 26 September 1901, p.3.

[13] ‘Mount Bischoff Extended’, Advocate, 6 September 1907, p.2.

[14] ‘Bischoff Extended’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 30 May 1913, p.1.

[15] ‘Mount Bischoff Extended’, Daily Post, 18 May 1915, p.8.

[16] HK Wellington, A century of tin mining, p.58.

[17] HK Wellington, A century of tin mining, p.61.

[18] ‘Waratah: 8-ton boiler raised from Bischoff Extended’, Advocate, 24 March 1933, p.8.

[19] James Smith notes, ‘Exploring’, NS234/1/14/3 (TAHO).