In summer you can easily wade up the Lea River beneath the beetling cliffs along the northern edge of the Middlesex Plains. Only by then doubling back can you find a mullock dump partially blocking the river, and above it a 30-metre-long tunnel into the cliff, where the remains of a skip and a rusted lantern testify to the past use of the rotten wooden rails. The price of gold is attractive in depression times, and it was in the wake of the 1891 depression that Lou Thomas first struck gold here. In 1931, during the Great Depression, depreciation of the pound boosted the gold price, an action repeated in 1952. Each time the miners returned hoping to plunder the Black Bluff or Lea River reef that had failed to yield its treasure last time around. Others, like Cliff ‘Dingo’ Beswick in the 1960s, chipped away in the main adit as a hobby, bothering more nesting swallows than gold buyers.

The mine’s only long-term resident, Walter Malcolm Black (1864–1923), probably spent a thousand pounds or so here. He was a remittance man—his family paid him to stay away from them. Black was the second son of grazier Archibald Black of Gnotuk, near Camperdown, Victoria, and a nephew of powerful Victorian squatter Niel Black.[1] Of medium build, 70 kg and 177 cm tall, Black was raised in the Presbyterian faith of his Scottish ancestry and, like many a grazier’s son, he was educated at the prestigious Geelong Grammar.[2]

In 1885, at 21 years old, he won an out-of-court settlement over his late father’s estate, which amounted to government debentures worth £7124.[3] The terms of settlement apparently included a deal that he stay well away from home.[4] His crime against his family, if there was one, is unknown, but in 1886 he was a grazier at Lila Springs Station, in the Warrego district, New South Wales, and in 1891 he was out at Bourke.[5]

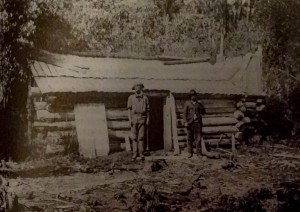

Black’s later movements give the impression of being directed by the need of distraction. His nest egg probably satisfied his financial needs. By 1894 he had renounced grazing for a mining career, possibly at the Western Australian gold rushes. In 1905 he was in Tasmania, occupying Lou Thomas’ recently renovated log hut at the top of the 90-metre-high cliff in which several drives sought that elusive lode. His introduction to the Middlesex Plains area was probably Deloraine doctor Frank Cole, who at one stage applied for land at Lake Lea, where he was said to be planning a summer resort and sanatorium.[6] The area Cole applied for later became known as Blacks White Grass, and Black was said to be the owner of a boat on Lake Lea.[7] In 1909 he asked the Meteorological Office of the Department of Home Affairs to send him a rain gauge, which he attended conscientiously for six years.

Black soon met his closest neighbours, Middlesex Station tenants Frank and Louisa Brown, plus William Hitchcock, manager of the Shepherd and Murphy tin, tungsten and bismuth mine at Moina. Later, Cradle Mountain enthusiast Gustav Weindorfer joined him in the high country. Educated men, Hitchcock and Weindorfer were important contacts because they were fellow converts to the ‘bush brotherhood’ and enabled an exchange of news, books and magazines. Illuminating titles like When earth was young, The great age, Waterfall and the Bulletin helped them keep a fragile hold on what must sometimes have seemed a world far removed. Black loved botany. For recreation, he could ramble up the Lea River in search of Blandfordia blooms with his sheepdog, take a row on Lake Lea, or track down his grey horse, Blue Spec, named after the 1905 Melbourne Cup winner, who roamed the woods with a bell around his neck.

However, Black is best known for his part in a legendary 1909–10 Cradle Mountain expedition. Kate Weindorfer, Ron Smith, Black and his sheepdog were there on the Cradle summit in January 1910 when Gustav Weindorfer proclaimed the need for a national park ‘for the people for all time’. This statement anticipated the establishment of both Waldheim (‘forest home’) Chalet at Cradle Valley and today’s Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park.

Black returned to his unnamed log hut. Perhaps because he had scoffed strawberries from Black’s garden, Government Geologist WH Twelvetrees took an optimistic view of the Black Bluff mine when he inspected it in 1912. However, Black never found his gold lode. Frustrated with the mine, he prospected as far afield as Granite Tor and the Dove River gorge, armed with a £75 government advance granted under the Aid to Mining Act (1912). Keeping the rain gauge only seemed to dampen his spirits. ‘I am heartily sick of things here,’ he wrote in 1915, ‘and I want to go down … and take a contract digging spuds—something to do at any rate … Measured 110 points this morning and raining still—over 6 inches this week’. In October of that year Black rewound his age by six years to 45, enabling him to qualify for war service and join up as a private in the First Remounts. He took the rain gauge, his books, his horse, saddle and bridle down the Five Mile Rise to Lorinna and sold them to fellow prospector Syd Reardon for £5.[8] Blue Spec may have passed to another Lorinna identity, Bert Nichols, who was known to use a grey mare by that name to transport his wallaby and possum skins.

Black served his time in Egypt without seeing the battlefront. However, war service aggravated a susceptibility to pleurisy which he had first contracted in Australia. At Heliopolis, Cairo, in 1916 he was struck by a galloping horse, breaking two ribs and damaging others. After that, every cold he caught turned into pleurisy, a condition which was exacerbated by another rib injury sustained when he fell down a manhole while aboard the Devon on his way home to Tasmania. Black spent ten days in hospital upon arrival in Hobart, and was discharged as permanently unfit in January 1919.[9] However, instead of returning to Black Bluff, he took advantage of the Returned Soldiers Settlement Act (1916) by market gardening a free land selection at Tolosa Street, Glenorchy. His restless ways continued. Soon he was grazing at Bellerive.[10] After a stint working at the cement works on Maria Island, he was admitted to the no.9 Military (Repatriation) Hospital, Hobart, where he died on 31 June 1923 at 58 years of age.[11] He was intestate, his probate being valued at a little more than £19.[12] That family nest egg was long gone.[13]

So was Black’s rain gauge. Syd Reardon was delighted to have it—and not because of an interest in precipitation. The only liquid Reardon cared about came in a bottle. Every month the Meteorological Department sent out a chart on which to plot the rainfall figures. Reardon saved them up and used them to wallpaper his hut. Meanwhile, young Harold Tuson delivered the gauge to the Lorinna State School, where for a time the teacher, Ivy Lloyd, kept up the rainfall records. However, when she fell ill and moved to Bothwell, the meteorology of the Middlesex Plains area drifted back into obscurity.

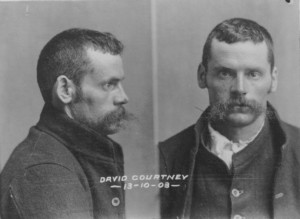

Dave Courtney with the beginnings

of his moustaches, in 1903 mugshots.

From GD63-1-3, TAHO.

Until legendary stockman Dave Courtney came on the scene. How Foley, the Divisional Meteorologist, came to choose the famously sullen Middlesex Station ‘mystery man’ as an ‘observer’ is hard to imagine. Yet their meagre exchanges show Courtney to be the one reliable record keeper in a dynamic tenancy. In August 1928, for example, Foley asked Courtney why no rainfall records had been received from Middlesex Station for six months. The bearded wonder responded that ‘since February last I have been away and the other man who was left in charge did not take the other rain’.

Courtney’s replacement Ted Farrell maintained the records for a time. Sometimes in winter Middlesex was cut off by snow drifts. Foley sent Farrell a snow gauge to measure that as well as the rain, but the stockman had moved on. Next man Bill Ward refused gauge duty, and when in December 1932 Ben Brown took over the station the snow gauge was missing. Alex Burnie replaced Brown in November 1934 and records again lapsed. Burnie left Middlesex, Dave Courtney returned—no rain gauge this time. Where was it? The Meteorological Department tracked down Alex Burnie in Queenstown in 1940, when he denied any responsibility, ‘I left Middlesex in May 1938 and all gauge [sic] were in good order then’.

The family of Middlesex Station grazier JT Field sold the property after his death in 1940. New owner, saw-miller FH ‘Cocky’ Haines, was more interested in millable timber than in raising stock. The station gained a strange new tenant called Frank Whitworth. In April 1946 he asked the Meteorological Department for ‘a suitable outfit for taking rain, temp records’ and a record book. ‘I am taking over a certain portion [of Middlesex] (which will be named Brayfield)’, he wrote. ‘I expect to be here for a considerable time’. Whitworth’s Brayfield letterhead, which included postal, telegram, cable and street addresses, supported this expectation. Unfortunately, one snowy winter at Middlesex consigned Brayfield to history. Whitworth scurried away to the sunnier climes of Port Sorell, taking the gauge with him.

So the rain on the plains splashed silently on the earth again, and the unmeasured hail clanged on the station roof. A hot fire took out Black’s log cabin. An adit packed with ancient, weeping gelignite is all that now signifies the remittance man’s tenancy of more than a century ago, and should a foot fall too heavily in that Lea River eyrie, more than a winter deluge may rain down on Middlesex.

[1] Birth record no.7299/1864, Victoria.

[2] ‘Personal’, Camperdown Chronicle, 9 August 1923, p.2.

[3] ‘Supreme Court’, Age, 27 February 1885, p.6.

[4] Harold Tuson, interviewed at Canberra, 11 May 1995. He met Black many times at the Mail Tree, Middlesex Plains, and once at Lorinna, and recalled that he was a ‘remittance man’.

[5] Notice, New South Wales Government Gazette, 19 March 1886, p.1983; ‘Quarter sessions’, Western Herald, 10 February 1891, p.2.

[6] ‘EJA’ (Dr EJ Addison), ‘On the roof of Tasmania’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 1 March 1907, p.4.

[7] Ken Cook, interviewed 8 August 1993; ‘LJB’ (Lionel Brown), ‘Middlesex: a tourist resort’, Examiner, 11 February 1909, p.3.

[8] Harold Tuson, interviewed at Canberra, 11 May 1995.

[9] World War I service record. See https://www.awm.gov.au/people/rolls/R1791278/

[10] Supplemental electoral roll for Commonwealth Subdivision of Franklin, 1919, p.3.

[11] ‘Items of interest’, World, 2 July 1923, p.4.

[12] AD963/1/2, no.1057 (TAHO).

[13] AD963/1/2, no.1057 (TAHO).