Tasmania has produced some disastrous mining ‘bubbles’. Stamper batteries and water wheels were rushed to the ‘Cornwall of the Antipodes’, the Mount Heemskirk tin field, in the early 1880s.[i] In the following decade the hydraulic gold craze crossed the Tasman Sea from Otago, while in 1910–12 the discovery of a so-called second Mount Lyell mine was celebrated in the Balfour copper boom. All of these were spectacular failures.

The ‘Broken Hill of Tasmania’ was another case of catastrophic piggybacking.[ii] It began in 1885 with prospector WR Bell returning to Tasmania from an exploratory tour of the Barrier Ranges silver field—later to become famous as the Broken Hill field—in western New South Wales. Bell put his Broken Hill experience to good use at home in the next five years, making a series of silver, galena and lead discoveries.[iii]

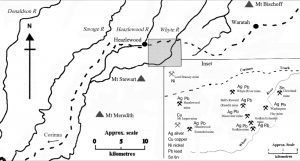

Among them was the Bell’s Reward mine on what became known as the 13-Mile silver lode, since it was 13 miles (about 21 km) west of Waratah, in Tasmania’s west coast mining province. However, it was the adjacent Godkin Mine that grabbed the headlines—and shareholders’ wallets—when in 1888 the Broken Hill silver boom reverberated across Tasmania. Never was there a better example of needless infrastructure spending before a mine was proven, or of the blinding effect of ‘mining fever’, than the Godkin.

Broken Hill invigorates the Tasmanian silver mines

In June 1887 Bell and his friend and business partner James ‘Philosopher’ Smith were granted 20-acre reward leases at what became known as the Bell’s Reward and Discoverer Mines respectively.[iv] Axes rang in the forest and cross-cut saws echoed in sawpits as a new mining village known as Heazlewood was established. Myrtle timber served for mining props, rails, building timber and firewood. Within a few years, five mine managers, two carpenters, a sawyer, a constable, a baker, a bank manager, three other storekeepers, a cricket team, hoteliers Joe and Emma Jupp and a branch of the Amalgamated Miners’ Association all called Heazlewood home.[v]

Other prospectors arrived on the 13-Mile, including 23-year-old New Norfolk prospector Norman Godkin, representing the Dunrobin Prospecting Association.[vi] A touring phrenologist, Professor Klang, claimed to have divined Godkin’s suitability to a mining career from reading the bumps on his head, vocational advice which his customer adopted.[vii] Working south from the Bell’s Reward, Godkin found a gossan outcrop close to the northern side of a small tributary flowing into the Whyte River. The Godkin Mine was born.

Since Broken Hill was the model for development at the 13-Mile, the services of a Broken Hill manager were deemed essential. The Bell’s Reward syndicate rejected Lane, manager of the Block 14 Company mine at Broken Hill, after he demanded a salary of £2000 per year, plumping instead for Edgar L Rosman, former mine manager for the Broken Hill Proprietary itself.[viii] The pedigree of Arthur Richard (AR) Browne, the Godkin Silver Mining Company’s (GSM Co’s) Broken Hill man, was even more impressive. The English-born nephew of the Marquis of Sligo, he was educated at the Freiberg School of Mines, Saxony.[ix] Significantly, neither of these men had experience of Tasmanian geology, geography, climate, terrain or transport infrastructure.

In 1891, only months before a severe economic downturn, Bell and Smith floated the Bell’s Reward and Discoverer mines, pocketing £3000 each from their sale.[x] The shareholders of the Bell’s Reward Silver Mining Co, an under-capitalised, privately subscribed Melbourne company, grew dispirited in 1893 after two years of fruitless work when water burst into a crosscut, flooding the main shaft.[xi] By then the true meaning of the Bell’s Reward was apparent on the hill above Burnie, where Bell had used his share of the proceeds to raise Glen Osborne, still one of the city’s finest homes. This remains the second most impressive product of the 13-Mile field, albeit physically distant from the mines themselves.

Tramway to nowhere

The most impressive product of the 13-Mile field was the Godkin Tramway. Having raised much more money than any of the neighbouring mines, the GSM Co was able to exercise its delusions of grandeur. During winter the dray track between Waratah and the 13-Mile mines was a sea of mud. Possibly with Broken Hill’s Silverton Tramway in mind, the GSM Co took matters into its own hands. The well-known Huon timber tramway builder known as John Hay no. 2 (junior) was engaged to deliver the mine from isolation. He surveyed and built the 3-foot-6-inch gauge horse-drawn wooden-railed Godkin Tramway at a cost of about £7000, the wide gauge having been chosen to connect the line with the Van Diemen’s Land Company railway from Waratah to the port of Burnie.[xii] The Godwin Tramway Act (1891) empowered the company to charge neighbouring companies for freight on the line, potentially placing it in a position to dominate the mining field.

Early bush tramways were constructed of whatever timber was available locally. Hay would have been familiar with the process of clearing and levelling the route, splitting myrtle sleepers, sawing and morticing the wooden rails and securing the line with gauge sticks. He set up a sawmill to cut the rails. The tramway rested on cross logs, on which were placed stringers, then four-inch slabs across those. The wooden rails were fixed on top of the slabs. Trestles were necessary in several places, but no ballast was used. Steel rails were placed on some of the curves on the line.[xiii]

The Godkin Tramway must have rivaled the famous Zigzag Railway in the Blue Mountains of New South Wales for switchback bends. At one point passengers could see two other sections of tramway and the Whyte River stretched out beneath them. The views were spectacular: ‘Here and there magnificent gullies and ravines, precipices of 200 ft or 300 ft on one side or the other that made one’s blood run cold to anticipate an overthrow’.[xiv] Yet it was said that the line enabled one horse to draw two tons of freight and/or passengers, with four trips possible in a day.[xv]

The mine remained unproven, but excitement mounted as some Godkin silver was smelted into a pendant for the governor, Sir Robert Hamilton.[xvi] Tramway builder Hay was a ‘strict total abstainer’, but soon he also became intoxicated—by silver. While constructing the tramway he struck his own silver lode near the Whyte River, floated a company, installed a concentrating plant alongside the tramway and set it up as the custom crusher for the district.[xvii]

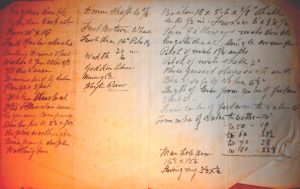

In mid-February 1891 Minister of Lands and Works, Alfred Pillinger, opened the 4.8-km-long first stage of the Godkin Tramway to the bridge over the Whyte River.[xviii] Now the mine could be tested. The 200 tons of Godkin ore reported to be ready for export could be sent out.[xix] Pumping and winding machinery could be brought to the Godkin, enabling sinking to prove whether the mine lived down. Tenders were called for the supply and erection of 40-ton and 80-ton water jacket smelting furnaces at the mine and for the construction of a police station at ‘Godkin’s and Heazlewood’.[xx] The arrival of machinery in July 1891 also warranted a celebratory banquet in Waratah and, more ambitiously, a christening ceremony on site on the mine’s southern section.[xxi] Mine manager Browne guaranteed one of his invited guests ‘a regular little spree for the men & the visitors’.[xxii]

Getting to the spree was a challenge. A party of guests, including Miss Seagrave, Browne’s future bride, left Waratah by coach and horseback for the start of the tramway. The coach broke down on the Magnet Range, forcing its passengers to wade through knee-deep mud for about a kilometre to the rails. At the mine, the Melbourne-based Austral Otis Elevator and Engineering Company boiler was inspected, after which Miss Inge and Miss Seagrave set the machinery in motion for the first time.[xxiii]

[i] The phrase ‘Cornwall of the Antipodes’ was credited to John Addis, manager of the Prince George Mine on the Mount Heemskirk tin field, in 1881 (‘Mount Heemskirk’, Mercury, 7 December 1881, p.3).

[ii] ‘A Bushman’, ‘The Whyte River Silver Field’, Mercury, 27 February 1890, p.3, described the field as being ‘in the opinion of many … destined to be the Broken Hill of Tasmania’.

[iii] For Bell, see Nic Haygarth, ‘Richness and prosperity: the life of WR Bell, Tasmanian mineral prospector’, Papers and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association, vol.57, no.3, December 2010, pp.203–35.

[iv] PB Nye, The silver-lead deposits of the Waratah district, Geological Survey Bulletin no.33, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1923, p.109.

[v] For Smith being elected vice-president of the Heazlewood Cricket Club, see JE Lyle to James Smith, October 1888, no.485; and 15 October 1888, no.500; NS234/3/16 (Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office, Hobart [hereafter TAHO]).

[vi] ‘In Chambers’, Mercury, 7 November 1888, supplement p.1.

[vii] Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 19 November 1890, p.2.

[viii] WR Bell to James Smith, 3 March and 4 March 1891, NS234/3/19 (TAHO).

[ix] ‘Mining news’, Daily Telegraph, 7 June 1889, p.3; ‘Queenstown notes’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 12 May 1900, p.4.

[x] Agreements dated 3 February 1891 and 15 June 1891, NS234/3/19 (TAHO).

[xi] J Harcourt Smith, ‘Report on the mineral district between Corinna and Waratah 28 July 1897’, Secretary of Mines Annual Report 1997, Parliamentary Paper 44/1897, pp. i–xix.

[xii] ‘Meetings: Godkin’s SM’, Mercury, 29 March 1890, supplement, p.1; Henry Penn Smith, Godkin Silver Mining Company, to JW Norton Smith, Van Diemen’s Land Company, 23 February 1891, VDL22//21 (TAHO).

[xiii] Arthur R Browne to JW Norton Smith, Van Diemen’s Land Company, 27 September and 4 October 1891, VDL22/1/21 (TAHO).

[xiv] ‘Whyte River silver field’, Launceston Examiner, 22 July 1891, supplement p.2.

[xv] ‘The Godkin Tramway: opening ceremony’, Wellington Times, 18 February 1891, p.3.

[xvi] ‘Personal’, Daily Telegraph, 1 October 1920, p.8.

[xvii] ‘Mining’, Mercury, 30 January 1891, p.3; ‘Obituary’, Examiner, 16 May 1902, p.7.

[xviii] ‘The Godkin Tramway: opening ceremony’.

[xix] ‘Waratah notes’, Wellington Times, 27 May 1891, p.3.

[xx] Adverts, Daily Telegraph, 10 June 1891, p.1 and 22 August 1891, p.7.

[xxi] ‘Starting the Godkin machinery’, Mercury, 20 July 1891, p.3.

[xxii] Arthur R Browne to JW Norton Smith, Van Diemen’s Land Company, 12 July 1891, VDL22/1/21 (TAHO).

[xxiii] ‘Starting the Godkin machinery’. Details of the boiler inspection can be found in AC705/1/1, 1885–1898 (TAHO).